The origin story of the Black List is almost mythic: In 2005, film development executive Franklin Leonard sent an anonymous survey to every Hollywood producer he had met with that year, asking them to name their favorite screenplays they’d passed on during the year because the scripts didn’t match their needs. In the movie industry, producers often encounter the same set of screenplays, both because writers’ agents and managers blitz the studios with new work and because the executives share their favorites among themselves. Leonard compiled a list of the favorite unproduced scripts and, at the end of the year, sent the producers the results. It went viral. The top two screenplays on that list were Things We Lost in the Fire and Juno. Subsequent editions of the Black List contained Oscar winners Argo, The King’s Speech, Slumdog Millionaire, and Spotlight.

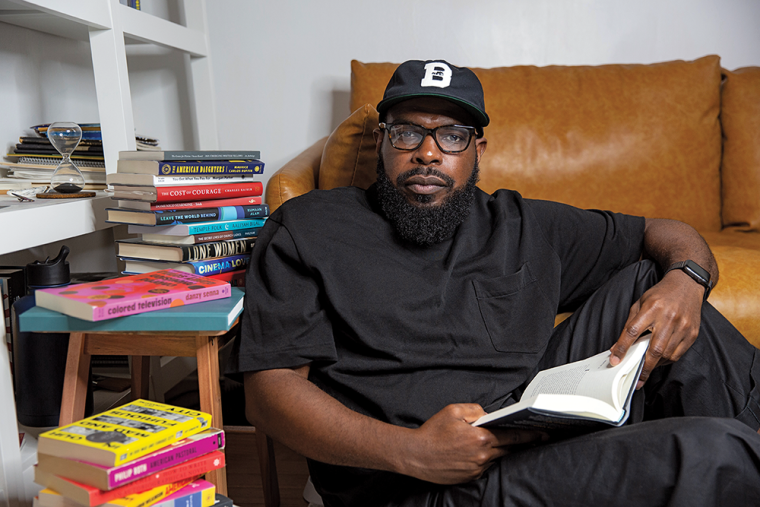

Randy Winston is overseeing the Black List’s expansion into fiction. (Credit: Zach Gross)

In 2012 the Black List added a website where screenwriters could upload their scripts for a fee in the hopes of getting them produced. And in September 2024 that website added fiction to its list of accepted genres—a move that could create a new pathway for novelists to get published.

Unlike the original Black List, the website requires writers of both screenplays and novels to pay for attention. Creating a profile and listing projects on the site is free; for $30 a month writers can post their manuscripts for agents, editors, and film executives to download, read, rate, and consider acquiring. Picture books, novellas, and short story collections are not accepted, nor is nonfiction, except for memoir.

An evaluation and rating of the first ninety to a hundred pages of a manuscript, performed by industry professionals with at least one year of experience, costs $150. The ratings are broken down into nine components: Premise, Plot, Originality/Creativity, Character Development, Dialogue, Setting, Prose, Themes, and Pace. Each manuscript also receives an overall score, which is meant to capture “the feeling you get reading something that makes you go, ‘My goodness! Everyone needs to know about this!’” says Randy Winston, the former director of writing programs for the Center for Fiction whom Leonard appointed to oversee the Black List’s fiction enterprise.

Writers can choose to make their evaluations and component scores visible to industry professionals, or they can hide everything except the overall score. If an overall score comes in at eight out of ten or higher, the Black List helps elevate the manuscript with two free months of hosting and two additional reviews, as well as inclusion in a weekly e-newsletter to industry professionals. Writers can apply for need-based fee waivers once a year.

Paying for an evaluation also makes writers eligible for the range of awards the Black List offers, including a $10,000 unpublished novel award in seven genres and a partnership with Simon Kinberg’s Genre Films to offer a $25,000 television or film option.

“We think of the Black List as a large metal detector going through haystacks everywhere,” says Winston. “A lot of agents and editors have a ton of submissions in their inbox; we hand them the good stuff so they can find something amazing.”

Winston hosts the Black List’s new conversation series, Read the Acknowledgments, a live visual podcast released a few times a month that features discussions of the business of books and writing. Each episode, recorded on Zoom, consists of two interviews with authors, editors, agents, booksellers, or librarians.

In one of its many collaborative ventures to reach writers, the Black List partnered with the Authors Guild to offer an online information session in October; the recording is available on the Authors Guild’s website.

Winston says that numerous literary agents from both large and boutique agencies have signed up to peruse the site. Some of them use the Black List as a more curated supplement to their slush pile. Jordan Hill, an agent at New Leaf Literary and Media, notes that for writers without representation, the Black List eliminates the work of researching agents and querying. And for agents like her, the ability to filter manuscripts by highly specific genre (fantasy and science fiction each have ten subcategories, for example) and look at other industry professionals’ ratings and evaluations will make it easier to find promising projects.

But for writers hoping to sign a major deal, the Black List’s rating system can also be frustrating—and what works for screenplays may not work in the same way for fiction. Diane Hanks, an author and screenwriter in Massachusetts, has paid for dozens of evaluations from the Black List for thirteen scripts she submitted in years past. Two of her screenplays were optioned but not produced; one of those became her narrative nonfiction book, The Woman With a Purple Heart (Sourcebooks Landmark, 2023). Her work ranks in the top 1 percent on the site.

“I send something in because I want to see where I am and what needs to be fixed,” Hanks says.

During beta testing for the fiction site last summer, Hanks was invited to create an account and upload a novel. But in her first review, she felt the glowing praise in the evaluation didn’t square with the low numerical marks. She also didn’t think it made sense to evaluate a novel based on the first third, before the big surprises arrive.

In the Authors Guild info session, held in October, Leonard addressed the reason for the sample length. If someone wrote a mediocre six-hundred-page novel, he thought it would be unethical to encourage them to pay for a complete manuscript reading. “If you ask anyone,” Leonard said, that first hundred pages “is a pretty good way to determine, ‘Is this something I want to keep reading?’”

Hanks recommends the Black List to other writers but advises them to make sure their work is top-notch before submitting and not to be discouraged by a low score. “I know so many people who just gave up,” she says.

One of those people is John Singh, a writer in Los Angeles whose agent could not sell his first novel. In early September he posted it to the site and paid for two reviews. Like Hanks, he received glowing feedback that felt at odds with the overall score of a five in both cases.

On September 24, he looked at every score listed on the Black List’s fiction site up to that point and calculated the average at 5.27. Not a single novel had received an eight or above. “They’re saying that nothing that’s been submitted so far qualifies as good,” he says. Singh thought it could be damaging to his efforts if the novel appeared on the site with the low rating, so he closed his account after just three weeks.

Leonard and Winston acknowledge that not every manuscript is going to be highly rated, but they believe that is the key to the site’s power. In the Authors Guild session, Leonard explained, “Our job is not to drive industry professionals to every manuscript. Our job is to drive as many industry professionals as possible to manuscripts that we believe to be strong. And if we’re not getting traffic for your manuscript on the site, you should probably stop giving us your money.” Still, for writers who are ready for the exposure, the Black List may serve as a key to a door that is all too often closed.

Jonathan Vatner is the author of The Bridesmaids Union (St. Martin’s Press, 2022) and Carnegie Hill (Thomas Dunne Books, 2019) and teaches fiction writing at New York University and the Hudson Valley Writers Center.