I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.

—Audre Lorde

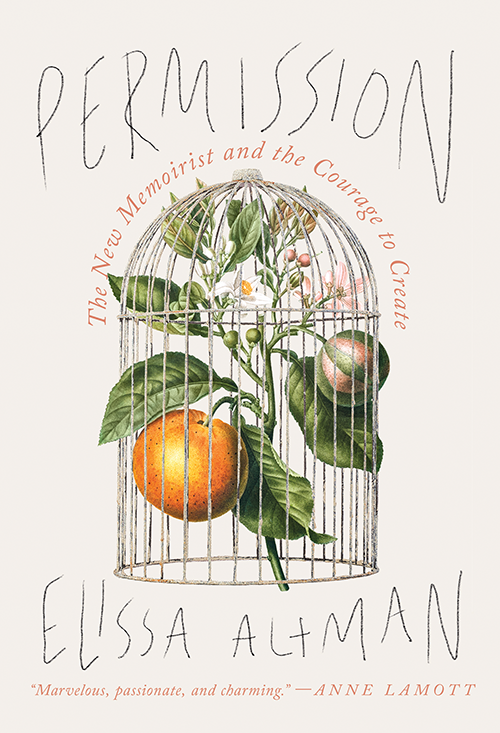

Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create (Godine, March 2025) by Elissa Altman

We are the storytelling species; we make art to metabolize and clarify experience, to find the truth, to make meaning.

We are the crafters and sharers of narrative. We are the yarn-spinners and the myth-makers, the truth-tellers, the searchers. We write, we paint, we sculpt, we sing, we make music to make sense of our lives and to create order where there is disorder. As Robert Macfarlane writes in Underland, it was the earliest humans who held their hands up against the wall of a cave in Spain and spat out a mouthful of red ochre dust to form a handprint that said, This is my story. I was here. Remember me.

Our stories bump up against the stories of others. Unless we are living in seclusion, or in a nunnery, or in a cave on a mountain in Tibet, our lives are inevitably intertwined and linked: they overlap like the intersection on a Venn diagram. Interdependence is defined by the Buddhists as being profoundly connected, and it is the nature of reality, and of human life. None of us lives in a vacuum; our existence overlaps with and depends upon the existence of others.

If it is human nature to mold and shape the truth, then what is the difference between truth and fact? How do they touch issues of ownership and permission? The psychiatrist and trauma expert Bessel van der Kolk spoke on Krista Tippett’s On Being about the concept of individual truth: put five adult siblings around a table and ask them what happened on Christmas in 1978 when Daddy got drunk on the Jim Beam, and they’ll all tell you a different version of the story, including Daddy didn’t drink. Each of those is a version of the truth as seen through the lens of each siblings’ experience, and each is therefore valid, but there can be only one empirical fact. Siblings will fight tooth and nail to prove that their truth is the truth, and the only real (and therefore valid) one. But truth is always filtered through the passage of time, through one’s eyes, through one’s worldview. In 2017, when Donald Trump was a newly elected American president and millions of women converged on Washington, DC, to protest, he is reported to have gazed out the window at a vast sea of pink hats, enthralled at all the women who were there, he believed, to celebrate and adore him. This was his truth, despite the veracity of the situation: the empirical fact was that they were there as an act of enraged dissent, not celebration. Still: a filter is a filter, whether we agree with what it shows or we don’t.

![]()

The act of writing memoir or personal narrative can be terrifying, and—I am sorry to say—these feelings do not ever abate; at best, we learn to live with them, cope with them, excavate them, metabolize them. It is understood, although rarely elucidated (except quietly, in whispered hushes, and mostly in therapists’ offices), that much of the fear of writing memoir has to do with warnings so ancient that they have become embedded in our psyches. We might be called a liar, a fabricator, a falsifier-of-the-truth. We may be told that the personal essay we’ve written comes from a grudge: you really hated that third cousin once removed, and so you’ve decided to tell the story about why she was sent away for a while when you were teenagers. We may be told that it’s just about revenge: your mother was so hideously cruel to you that you’ve decided to write about her so that everyone knows she’s not the perfect church lady everyone thinks she is, and now she’s too old to fight back. Or that abusive guy you were briefly involved with in the nineties is going to show up again in a dream sequence involving his getting drunk at an office party, and even though you’ve changed his name, likeness, and job, he will likely recognize himself. After writing her (then) shocking and revelatory memoir about her relationship with J. D. Salinger, At Home in the World, Joyce Maynard was called everything from self-absorbed to a hanger-on to (in the Washington Post) incredibly stupid, in spite of Salinger’s withering and predatory treatment of his former student, who, in 1972, left a full scholarship at Yale as a freshman to live with him when she was eighteen and he, fifty-three. When Paul Theroux documented his friendship-gone-sour with his mentor, V. S. Naipaul, it was said to not be revenge, but just an examination of the arc of a literary friendship. Maynard, however, made the choice to tell her story and received—and continues to receive—so much vitriol over the book that she, in her own words, might as well have killed Holden Caulfield himself.

But whoever we are and however seasoned we are in the work we do, a large component of this fear of writing comes from shame. Together, fear and shame will conspire to quash creativity at every step, and they will, if we allow them to. How do fear and shame play a role in making the choice to write? What happens if we ask permission to write a particular story and that permission is denied? (Imagine this scenario: Dear X: May I write a memoir documenting your abusive treatment of me as a child?) How many vital stories are not being told—memoirs written, movies made, art made, souls healed—because of fear and shame?

And yet, the issue of creative permission and the stories we must tell is a tentacled moving target. Did Sally Mann have permission to famously photograph her young children unclothed, in the name of art? Her children—Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia—were photographed by their mother, as one journalist said, with lapidary beauty. The photographs created a firestorm of opinion, which continues to this day. In an interview upon the publication of her memoir Hold Still, she cited context: When I was immersed in motherhood and saw my children running naked every day, I found nothing unusual or unsettling about it, but can now, decades away from that time, understand how someone not so immersed might. Without the context of our very private farm and the protection of the cliffs and the river, the pictures would never have been taken, I’m sure of that. And that is why it was so understandably hard for some viewers to understand the work—they had to know about the context.

Anyone who has spent any time in the rural shelter of a small country farm with no one around for miles has likely seen the carefree romping of young children who, depending upon the context, may or may not be clothed. This, however, is not at question, at least not as I see it: every one of us who has been to a beach or to a city park with a sprinkler has seen little ones running around in gleeful freedom and delight before being wrapped up in towels, whereupon they almost instantly fall asleep. Many of us have either photographed or been photographed as very young children in bathtubs, or baby pools, or on the beach on a hot summer day, all of which are (we hope) acts of innocent affection. Likewise, Mann’s children were apparently used to their mother photographing them all the time, clothed and unclothed. The question is not about whether she should have photographed them, but whether or not she should have published those photographs before her children were of age to give their approval, or not. I remain on the fence; context always matters. I have no children, but I am also the survivor of child sexual trauma, and I turn into the Hulk if I have the sense that a child is in danger of any kind. I also believe that Sally Mann is a magnificent photographer and visual storyteller who deeply loved her kids. She could have waited to publish the photos; in my opinion, the rules change when it comes to children who cannot say no.

Where else does permission figure in in a world where artists can be canceled, their work tossed into the dustbin of history for their (sometimes horrible) actions? Do I have permission to still publicly love the work of poet Derek Walcott, even after accusations of sexual impropriety against him dating from the time he was a professor at Harvard University and at my own alma mater, Boston University, where he was renowned long before the cases were brought against him for parading in the nude, and worse, in front of the massive window of his brownstone overlooking Bay State Road in Boston? Do I have permission to watch Annie Hall, Woody Allen’s masterpiece, and still consider it one of the finest movies to come out of the modern American film canon, even though he may be a monster? Closer to home, a neighbor of my childhood was thought to be a perfect example—pillar of her community, mother, expert party thrower, bank president—and every one of us wanted to be her or be like her when we grew up. How many of us got a glimpse of what a sadistic, alcoholic horror she was to her children when the garage door came down and the casserole went into the oven? Who among us has permission to tell that story? To tell that truth?

These questions hound me; as a teacher of memoir, I am faced with versions of them in every workshop I lead, when a writer says, I want to tell this particular story; it’s been haunting me for years and I have been writing it for years, but what gives me the right? I answer them: If this particular story touched you directly, you have every right to write it. To be so compelled to write a certain story—to mine it, excavate it, unravel it, clarify it, hold it up to the light and turn it around like a prism—is an act of incalculable bravery. There are pitfalls and hazards everywhere.

There is creative growth and transcendence when we sit with the discomfort that arises from being the truth-teller and the artist. We acknowledge it, feel it, then cast it off and overcome the fear and the shame that we are often faced with.

![]()

Janna Malamud Smith writes in An Absorbing Errand that creative fear and worry can come in every shape and permutation and from many root causes: It might come from disloyalty to your family of origin, who may see you as besting them. It might come from the fact that creative expression beyond the confines of your childhood crayons and coloring book is alien to them. It might come from fear of ridicule and disapproval—fear that you might make a fool of yourself in the eyes of your community and that ridicule might be projected onto the people you love. Smith calls discovering and following one’s creative impulse finding the latch, and she goes on to say that finding the latch is not simply about choosing something to work at; it’s about agreeing to enter into a complicated psychological space filled with ricocheting emotions.

All those lovely and atmospheric pictures of writers on Instagram and TikTok? I tell this to my students: they aren’t real. They don’t necessarily show the truth, the fear, the worry, the lost sleep over whether one is making the right choice: to tell the story now, or to wait until all parties are dead, or to not do it at all. There is profound discomfort in the creative process, and humans as a rule are not particularly comfortable with ricocheting emotions, which, the Buddhists might say, are another form of dukkha, or suffering. The ability to sit with difficult, often contradictory emotions—I have to write this story; I can’t write this story; I must write this story; I shouldn’t write this story; they won’t like me if I write this story; what will happen if I write this story; my grandmother will come back from the dead if I tell this story; nobody will believe me if I write this story; I’ll lose my family if I write this story; I have to write this story—does not come naturally to us as a species. But fear is not unique to the individual maker of art: not to you, or to me, or to the writers and creatives who came before us and who will come after us. If we learn to sit with it—to understand that fear, like joy, is simply an expected component of art-making—we will inevitably be graced with the kind of creative fulfillment that comes when we have transcended fear, when we know we have crafted something important and crafted it well. In my workshops, I speak of the imperative of emotional resilience in the creative process. When we commit to living a writing life with all of its snares and hazards and landmines, we do so knowing that it is not going to be easy; we can’t write anything without fully grokking this and accepting it as part of the process. The discomfort that comes with the process is as much a part of writing as paper is of a book.

Like any kind of anxiety uncontained, fear of the creative process will run roughshod if we let it.

When I am in the throes of writing a new book, I don’t sleep well. I often wake before sunrise, my jaw aching with the tension of sleep paralysis. I’ve long stopped believing I’d remember my dreams in the morning, so now, if I’m jolted awake at 3:23 a.m.—my witching hour for as long as I can remember, when I wake parch-mouthed and panting—I write them down in an illegible scrawl in the small notebook that I keep on my bedside table, even though I’m rarely able to make sense of them at dawn.

It feels as though I dream about my father every night, even though he died suddenly and violently two decades ago. I have told this to no one: I am certain his spirit still walks around, trying to rewind the tape, trying to pause the split second before his car was T-boned by a rusted-out Toyota filled with uninsured teenagers on a hot August Saturday morning in 2002; that I imagine his spirit pacing back and forth on that tree-lined suburban corner in Roslyn, New York, waiting for me to find him, to pick him up, to call the tow truck, to take him home. In my dreams, he is surprised when he realizes what has happened: that he was hit and the ambulances took him to one hospital and my stepmother to another, that he’d spend a week in the Bardo, hovering on the filmy plane between life and death until I removed him from life support and looked at him one last time before they wheeled him away, his mouth gaped open, vacant, in utter shock at what had befallen him, at what I had done, at the fact that he was gone. I believe—I am certain—that he thinks I betrayed him.

Most often, though, my father is in his late fifties when he comes to me, the age he was when I was in high school, he and my mother had divorced, and we spent every weekend together. The dreams are always the same: he glances past me but never directly at me, as though he’s looking at something in the distance. I talk to him, reach out to him, beg him to answer; he doesn’t respond. I call him on the beige rotary phone that hung on the wall of my childhood kitchen; I hear his voice clearly—It’s Cy Altman, I’m not here right now—and I leave him a message, but he never calls me back. Or I’m a fly on the wall at a large family gathering of the cousins with whom I no longer speak, and he’s in the den with them, having a cocktail. I call his name, but all that comes out of my mouth is a kind of bovine gasp. I see him in the way that Scrooge sees his past in A Christmas Carol; my father is a memory, a shadow, clear as a bell, but unable to respond to me.

I wake up panting like my terrier, and believe that he is angry with me because I’ve written something about us that perhaps I shouldn’t have. I imagine that I am dead to him, as I am to many members of my family for writing something that they felt was a betrayal. I didn’t toe the party line. I have finally chosen to end the intergenerational cycle of fear and shame, to tell our story of devastation and survival and sustenance, and to shed the shackles of creative suppression.

In choosing to write this story I was not supposed to tell, I have become the ghost, the family apparition that will simply not let our stories rest in peace.

![]()

Stories inhabit and possess us. They take over our lives; we cannot shake them. Stories intervene violently, writes Arundhati Roy. We must give them attention; we must give them air and water and light, like a garden. They must be respected, allowed to live, allowed to blossom, even if—especially if—we are haunted by them. In Body Work, Melissa Febos wrote, There is no pain in my life that has not been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.

Those of us who must write usually come to it early, even in childhood. When I was a child, I was a stutterer. As an adult, I told no one. I had been silent about it until I was asked by an interviewer on National Public Radio: When and why did you start writing? How did it happen for you?

An uncomfortably long pause: to implicate myself as a stutterer would bring shame to my family, whose children historically speak very early and in full and complete sentences.

I was a stutterer, I told the interviewer.

They went silent.

(No interviewer ever wants to learn, during an on-air interview, that their guest is, or was, a stutterer.)

—so the only way I could finish a thought, I added, was to write it down.

I grew up in a loud, pugnacious household in the seventies, the only child of two people who, at worst, loathed each other, and at best, tolerated each other. I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. Both of my parents were beautiful, highly creative people whose artistic callings went unfulfilled. My father, a World War II night fighter pilot, a brilliant advertising man and failed poet who carried in his heart the sorrow of creative disappointment throughout his life, and my mother, a musical performer, model, and television singer who gave up the only career she’d ever loved when she married my father and gave birth to me, nine months to the day from their wedding.

Do you know what I gave up for you? she says to me even now when she is enraged, heading into her eighty-ninth year. Who do you think you are?

Even now, after four books, countless articles and essays, I cannot answer my mother’s questions in complete sentences; the words fall out as a hiccup, a blip, a disconnect. A stutter.

But I know what she gave up. I know what haunts her creatively: it was the possibility of making musical art. The chance to fulfill her only creative dream. Her life’s regret; she made a choice. A baby, or her art. She chose to become a mother.

When my grandmother walked out on my father and aunt in 1926, she too made a creative choice, and another one when she returned. As I search for the jigsaw puzzle pieces that fit in, trying to understand why she left—these are core parts of the story—I land here: my grandmother had been a concert pianist at fourteen and was separated from her music when she married, four years later. She had her children five years apart, my aunt in 1918 and my father in 1923, and she fell into the deep postpartum chemical depression that afflicts most of the new mothers in our family, across the generations. Depression and the inability to fulfill her musical life likely resulted in psychic and emotional isolation, and she fled. When she returned at the height of the Depression—my grandfather held down two jobs and still didn’t have two nickels to rub together—a walnut baby grand Knabe piano was waiting for her in the living room of their Brooklyn apartment. Sitting next to her in the back seat of my parents’ Oldsmobile in the mid-seventies during a Sunday drive, I watched as her eyes closed and she began to doze off with both hands resting in her lap, moving back and forth—her right hand stretched wide and her thumb rested on an invisible middle C. As a young musician, I recognized the chord structure and the rhythm; she played the ghost of her beloved Chopin’s piano concerto in her sleep until the car came to a stop and she was jolted awake.

My mother and my paternal grandmother had no love for each other, but this is part of the story, and what bound and connected them: they both gave up music to raise children. I believe—this is conjecture; I will never know for sure—that my grandmother abandoned her family for creative survival and the visceral desire to make music the way she needed air and water. Conversely, my mother gave up her creative life to have a family, and it has haunted her every day since she married my father in 1962.

I believe the two of them regretted their decisions for the rest of their lives.

![]()

My parents both struggled with untreated, complex trauma: My father had been abandoned. My mother lives to this day with physiological dissociation, a kind of congenital analgesia; she didn’t know that she was pregnant with me for six months. Together, they yelled, they loved, they laughed, they fought. They lived bifurcated lives of rage and joy and the depleting exhaustion that follows, and I was a witness to their hours, like wallpaper. I began to stutter when I was very young; I couldn’t get a word in edgewise in what passed in their minds for civil discussion, and if I did, I was chronically interrupted midsentence: they corrected me, talked over me, got up and poured themselves more chianti just as I was about to get to the good part of the story I was telling them. They flipped the channels on the television set while I was trying to speak, as though I were invisible. Instead of demanding to be heard—throwing a temper tantrum or being otherwise destructive—I stopped finishing my own sentences. I learned instead to quietly watch and listen, and turned from speaking words to writing them. If I was ever going to express myself with words, I couldn’t do anything else but write.

Some children in the same position would be driven to paint, or draw, or bury themselves in learning how to play a musical instrument. My teenage neighbor Meredith in the next apartment, with whom I shared a bedroom wall, grew up in a restrictive religious household; her mother was a Holocaust survivor who had met her husband in Israel in 1968; they had both been in a displaced person’s camp in Germany after the war. Meredith grew up understanding that there were certain things that she was not allowed to say, to ask, to wonder about. Instead of writing about living with two parents who witnessed unspeakable horrors and what that meant for her, she asked her mother for a set of acrylic paints and a few paintbrushes and painted an entire floor-to-ceiling mystical universe of flowers and plants and toadstools on her bedroom wall, not unlike a scene out of Alice in Wonderland. Meredith could not speak her truth, but she could paint it, and she did. Years later, she became a professional artist.

Paper is more patient than man, wrote Anne Frank from her attic in Amsterdam before she was sent to Bergen-Belsen. At eleven, I read that sentence—I was still stuttering at eleven— and found it to be wholly true. I couldn’t speak without interruption and without stuttering, so I wrote, and I believed that my ability to express myself in this manner could never be taken away from me. No one could cut me off; no one would laugh at my attempting to tell a story about something I’d seen, or heard, or longed for if it was relegated to the page. No one would get up and walk away. No one would ever tell me that the stories I was writing were made up, figments of a bored child’s overactive imagination. Writing gave—and gives—me ownership not only of what I see around me, but of the words themselves that I use to express myself fully.

Words allow the stories that haunt us to move through the scrim of imagination and into a place of breath and life.

![]()

After my exile from my family, every part of my life began to disintegrate. It was so unexpected, so completely surprising and shocking, that I spun like a top. I obsessed over the loss of people for whom I had a profound affection, and who I assumed had been truthful in their lifelong affection for me. I wrote letters— long, overwrought letters—begging for forgiveness. I wanted my old life back. My health began to collapse; I fell into a suicidal depression; my use of alcohol as a crutch to get me to sleep every night nearly killed me. What had I done? I had made what Mark Doty calls an inquiry into memory. The past is not static, or ever truly complete, he writes in his essay “Return to Sender,” a piece about the intersection of betrayal and memory. As we age we see [the past] from new positions, shifting angles. When I wrote my book and revealed the truth about my grandmother abandoning my father and how it touched generations long after it happened, I, too, wanted to examine the past’s power over me and my father from new positions and points of view, and from shifting angles. It took years to comprehend the truth: that I had nothing to apologize for. I had revealed a story that had touched me personally and profoundly, and that made me who and what I am. I could not take on the responsibility of the reactions of others.

A decade later, I rededicated myself to the unknotting of a truth that is as vitally a part of my fundamental makeup as my blood type. My family had claimed that I revealed what I did as a way to hurt them, but they could never elucidate why. There is a difference between gratuitous creative revelation (and its twin, revenge) and the revelations that actually drive a story, and without which that story cannot be crafted. If we are to write, or create at all, we must do the very thing that is scariest: we must honor our creative hearts to overcome the greatest challenge that every artist faces, be it societal, cultural, or personal: the words you are not allowed.

That said: who are we to borrow the histories of others, alive or dead, whose stories are compelling, touching, devastating, but whose lives have not touched our own? What right do we have to rifle those lives of their flowers, to mangle a Woolfian phrase, and use them as the core of our own? When we write about those with whom our lives have not intersected but who we simply find interesting, or are in some way compelled by, that is not memoir; that is biography.

We have no right to rifle those lives of their flowers; those are the stories that do not belong to us.

When we write memoir, we also don’t get to character assassinate people—alive or dead—because it is convenient revenge masquerading as art, even if we feel that they deserve it. It may feel good at the time—take that, you bastard—but revenge writing results in flattened, one-dimensional characters, flattened narrative patterns, a deflating of the complexities of story. An important writer I know famously works out her rage at colleagues, former friends, and family members on the page: her work is lyrical and she is well known, so she gets away with it because she is also recognized as being too dangerous to cross.

We write for what we need as humans: meaning, purpose, and truth. There can be no victimhood, or self-pity. I once attended a craft talk that Dorothy Allison was giving, and she summed up her feelings about revenge writing this way: You want to write revenge? Then you have to write yourself as fucked up and shameful as your other characters are.

This work is not for the faint of heart; even now, after hundreds of essays and three memoirs, when I find myself knock-kneed and unable to move forward while I’m writing, I gird myself with the works of truth-tellers made famous for their art of revelation: Suzannah Lessard, Joy Harjo, Ocean Vuong, Barry Lopez, Joyce Maynard, Jericho Brown, Dorothy Allison, Ruth Ozeki, Melissa Febos, Patricia Hampl, Kathryn Harrison, Vivian Gornick, Honor Moore. After Gornick’s Fierce Attachments was published—a brilliant mother-daughter memoir that unfolds through a series of walks in the author’s childhood Bronx neighborhood—the author took to her bed when her mother read it. According to Mary Karr, Carolyn See famously collapsed with viral meningitis two hours after finishing the first draft of her memoir Dreaming. See claimed it was her brain’s way of saying, You’ve been looking where you shouldn’t. Suzannah Lessard was sliced out of the Stanford White family—White was her great-grandfather—after she published The Architect of Desire, in which she revealed White’s unquenchable and flagrant sexual appetite, the sexual abuse that several members of the family endured after White died, the silences kept, the secret pacts made to maintain appearances. Novelist and filmmaker Ruth Ozeki writes in her beautiful short memoir The Face: A Time Code about wanting to be good as a child and knowing that being good meant being reserved and private. When Ozeki shows her elderly parents her autobiographical documentary film Halving the Bones, she openly questions the reliability of memory and truth. Ozeki’s father asks her outright to never make a film about him. She gives her father her word. She also changes her surname—Ozeki is not her real last name—to prevent family embarrassment, but to also remain true to herself as an artist, and to keep writing and creating.

No writer ever writes alone. Every one of us is bolstered by others who have grappled with different versions of the same conundrum: to write the truth, knowing that there will be consequences, or not to.

We don’t choose to create; the creative life chooses us. Writers are viscerally driven toward truth and clarity; very few of us are willing to spend two years working on a book that has its roots in malevolence and poison. When storytellers move from silence into speech, we make new life and growth possible both for ourselves and our readers. We crack open the hard shell of shame, expose our stories to light and air, allow our work to breathe, and create magic. Whoever we are—published or unpublished writers; painters or musicians or chefs—if we don’t heed the call to create, and give ourselves permission, our worlds darken and fade. Our stories are stillborn; our lives thrum along on a dull, monotonous hum. The healing capacity of storytelling becomes stifled. Shame, that familiar state of excruciating self-consciousness, is permission’s plasma; it is shame that is weaponized by those who wish to silence people—almost always women—in their midst. Art-making is the antidote to shame: it diffuses it, releases it, casts it to the wind, allows the creator to breathe again, to heal ourselves and others, to move forward in our work and in our world with, if we are lucky, grace and humanity.

When we ask ourselves, Why am I choosing to do this, to write this story? we are expressing the innate shame that comes from the generations of family, the teachers, the clergy, the culture who have admonished us for believing we had anything to say.

Who do you think you are to tell this story?

The permission to write—to make art in whatever form it comes—is proprietary. It belongs solely to its maker. I was my grandmother’s granddaughter, and her story touched my life directly and impacted it forever.

Still, we must inquire and investigate our role in our stories, and our motivation behind writing them. There are always ethical concerns, and we would be irresponsible if we didn’t consider them. But every one of us is touched by the narratives that are embedded in our lives; this is the human condition, as ancient as the seas. The process of storytelling is paramount to species survival—consider the cultural stories depicted on Greek pottery in 400 BCE, in which entire myths are played out pictographically—and to the metabolization of joy and sorrow. This is why stories and our compulsion for telling them exists in the first place: as a way of remembering who we are, where we come from, what we saw, and what we know to be the truth. And that is the right of every artist.

![]()

Six months after my book came out, I phoned my aunt, then in her nineties, to wish her a happy Jewish New Year, as tradition requires one does with the oldest member of the family. We hadn’t spoken since the publication.

It was very brave of you to call me—she said coldly.

—but your story was not yours to tell, she added, taking nearly an hour to explain how I had singlehandedly destroyed our family by revealing a truth that she had spent almost a century concealing, convinced all the while that she had been successful, even as her brother had fed me the story from the time I could understand words.

I loved you, my aunt said to me, at last. And then she hung up. She would never take my calls or speak to me again.

Rejection is a key part of our core history, and as James Baldwin promised, one that I would write about over and over, until it became clearer and clearer, narrower and larger, more and more precise. As in Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water, in which a single family loses a member to drowning in every generation, in my family themes of primal rejection play out repeatedly in the narrative of our lives over the course of a century.

This was the story I was meant to write, and the reason I believe I was placed on this blue marble: to break the chain and free myself and anyone who comes after me from the strictures of shame encapsulating the myth of a mother who abandoned her husband and children almost a century ago. Through my writing about her, she has morphed from a one-dimensional, tiny, Sabbath-keeping demon to a perfectly imperfect human—a woman stuck in the Bardo between the old world and the new, grasping for some semblance of power and self-knowledge, and utterly devoted to the music that might have saved her.

In writing it, this is what I learned, and what every writer learns when they honor the need to tell their story: when we move from the silent to the spoken, we shed light on and create life where there was darkness and shame.

Still, the most difficult decision that any memoirist faces is whether or not our own kernel of truth is important enough to the story to honor and share: Without that kernel, a memoir has no soul. And with it, we risk everything.

From Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create (Godine, 2025). Copyright © 2025 by Elissa Altman. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Elissa Altman is the award-winning author of the memoirs Motherland, Treyf, Poor Man’s Feast, and the bestselling essay substack of the same name. A longtime editor, she has been a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award, Connecticut Book Award, Maine Literary Award, and the Frank McCourt Memoir Prize, and her work has appeared in publications including Orion, the Bitter Southerner, On Being, O: The Oprah Magazine, Literary Hub, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, and the Washington Post, where her column, Feeding My Mother, ran for a year. Altman writes and speaks widely on the intersection of permission, storytelling, and creativity, and has appeared live on the TEDx stage and at the Public Theater in New York. She teaches the craft of memoir at Fine Arts Work Center, Maine Writers & Publishers, Kripalu, Truro Center for the Arts, Rutgers Community Writing Workshop, and beyond, and lives in Connecticut with her wife, book designer Susan Turner.