Forty-five minutes into my Zoom interview with Mosab Abu Toha, a Palestinian poet and teacher who is the founder of the Edward Said Public Library, the first English-language library in Gaza, a door opens off-screen. Moments later a small hand clutches the poet’s shoulder. It is four-year-old Mostafa, who, after coming in earlier to say hello, has now returned with a very urgent question.

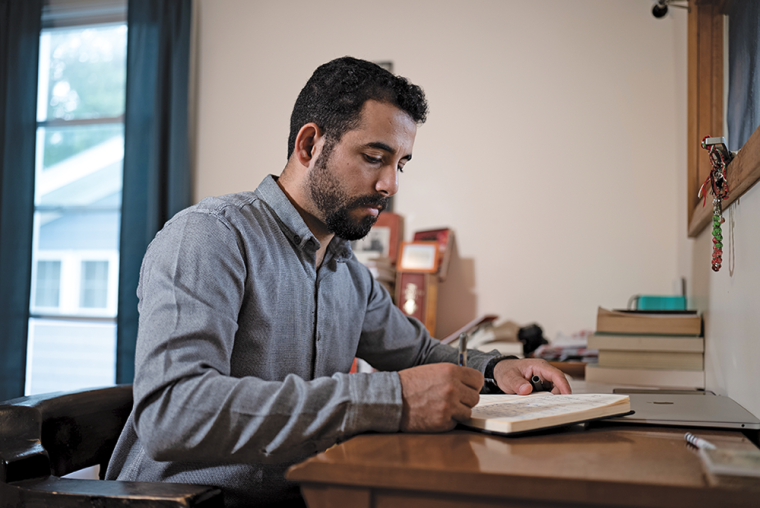

Mosab Abu Toha, author of the poetry collection Forest of Noise. (Credit: Dustin Tang-Chung, Blackfern Media)

“Papa, where is Yaffa?” he asks. Yaffa is Mostafa’s seven-year-old sister.

After Abu Toha suggests Mostafa check downstairs, it becomes clear to me that every aspect of the poet’s life and work, from his new poetry collection, Forest of Noise, published by Knopf in October, to this adorable interruption, has been marked by the brutality of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Born in Gaza’s Al-Shati refugee camp in 1992, Abu Toha has never lived in his homeland without war, but even in the face of almost certain death, he was reluctant to leave it. Although he and his family spent time in the United States while he completed a yearlong Scholars at Risk fellowship at Harvard University in 2020 and an MFA in poetry from Syracuse University in 2023, Abu Toha and his wife, Maram, returned to Gaza last year in hopes of building a life there with their children: Mostafa, Yaffa, and their older brother, eight-year-old Yazzan. But when war broke out in the wake of the October 7 attack by Hamas on Israel, the couple decided it was best to leave. They were given clearance to do so in early November 2023. However, before crossing the border at Rafah, members of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) plucked Abu Toha from a line of evacuees while he was holding Mostafa in his arms.

After a harrowing two days in Israeli custody, Abu Toha was released, and he and the family soon reached safety in Egypt and, later, Syracuse, New York, where they now live. However, the scars of a decades-old conflict and the ways it has shaped his life have not left him, nor does he want them to. In Forest of Noise as well as his debut collection, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems From Gaza (City Lights Books, 2022), which won the American Book Award, a Palestine Book Award, and Arrowsmith Press’s 2023 Derek Walcott Prize for Poetry and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, Abu Toha takes up the mantle of both poet and historian, chronicling the violence he has inherited, witnessed, and survived. In “Palestine A–Z” the abecedarian poem that opens Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, he writes of his grandparents’ expulsion from their home in Yaffa (also known as Jaffa) during the 1948 Nakba, the forced relocation of Palestinians from what is now Israel. Yaffa, now part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is the city after which his daughter is named. “[S]he speaks, and I hear Yaffa’s sea, waves lapping against the shore,” he writes in the first collection’s opening poem. “I look in her eyes, and I see my grandparents’ footsteps still imprinted on the sand.”

Like his debut collection, Forest of Noise is filled with depictions of children, from scenes in Abu Toha’s childhood to elegies for the children who have not survived. In one particularly haunting piece, “The Ball and the Bombs,” he describes the 2014 deaths of members of the Bakr family, a group of school-age siblings and cousins who were struck by Israeli missiles while playing soccer on a Gazan beach. Alongside these poems are moments of nostalgia and beauty—ones that, like Yaffa’s name, he hopes he can offer his children as a remnant of what displacement has destroyed. In “Palestinian Village,” the speaker parks his vegetable cart in an idyllic town, then reclines in a wicker chair near a pomegranate tree while a canary sings from above. It is a pastoral of what might be, even though the prospect of peace in Gaza seems dim. As Abu Toha explains during our interview in August, his poetry is both a blueprint and a legacy. “I, as a father, cannot take my child to the kindergarten where I went, to the playground where I used to play, or to the library where I used to borrow books,” he says. “So these memories help us re-create this stolen place, this destroyed place [for] when we have a chance to rebuild. It’s [also] one way for me to remember.”

During our conversation, Mosab Abu Toha and I discussed how Forest of Noise is more than a poetry collection; it is an inventory of what has been lost to occupation and destruction and a tribute to the hope Palestinian people continue to hold on to. We also discussed why the stories of children are central to the story of Gaza, what Abu Toha sees as his job as a poet, and how poetry can serve as an act of resistance, a call for solidarity, and a map for rebuilding in the wake of cataclysmic violence.

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear was only published two years ago, in 2022. When did you know you were writing a second book?

You know, I don’t work on book projects. I don’t sit and say, “Okay, I’m now going to write a book about nature, or about my experiences in Syracuse.” Most of my life I spent in Gaza, and between 2008 and the ongoing genocide, I’ve survived at least five [near-death experiences] with my family. When you are in the middle of a dangerous experience, you are writing about things that are very immediate: air strikes, the bombing of your house, the murder of your friends. I lost thirty-one members of my extended family in one air strike in October. So the intensity of what’s happening sometimes prevents you from reflecting on certain experiences, because this loss is never-ending. You tell yourself, “Oh, maybe you don’t have to mourn this now because you are going to lose something else in the next few minutes.” You try to be protective of your own feelings to prepare yourself for another heartbreaking piece of news. So the poems were about capturing the experiences I was having before they were lost. Some of these experiences were direct. But other poems are about people I know, or pictures of children who could be my children, who could be me. I have this feeling of responsibility to document what I am seeing right now, because tomorrow I will see something different. Whatever strikes me as a poet or as a human being, I document because it’s my duty as a poet to document everything that I see. That may be one definition of poetry for me, which is a combination of an experience and the emotions that come with it. About half of the poems in the book were written after October 7, while the other half of the poems were written before. But they are not so dissimilar because they are about the same experiences, the same people.

In an interview that appears at the end of Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, you explain that the Arabic word for poetry, sha’ir, does not refer to a particular form per se but to the feeling a poem produces. What feelings do you hope the poems in Forest of Noise evoke in your readers?

Arabic poetry has an older tradition. It goes back at least to the sixth century AD. And the Arabs had this definition of poetry: It should have a meter, a rhyme, and a meaning. So poetry is about feeling, and the poet is someone who has this destiny of being able to express how he and others feel. If the poet can put into words what he and others around him are feeling—whether it’s his own community or the nation of which he is a part—he succeeds as a poet because he is putting into words what other people are trying to [say]. But I would add to this definition. The poet [should have] the skill of using not only the right words, but the best words in their best order at the right time. During these hard times a poet should use the best of his words, put them in the best order he can, and then share his words immediately. This is something that can’t wait because it’s about people’s lives. I cannot wait until this [conflict] ends to tell people how I felt, or what they should do. When I write a poem and other people relate to it, and they read it to other people who [are struggling] to understand what’s going on, then the poem is working because it’s delivering a message that something is going on and [that] people need to act.

What struck me about Forest of Noise is that there are so many children in the book. There are children whose bodies are recovered from heaps of rubble, but there are also memories from your own childhood of seeing a helicopter fire a rocket for the first time, and scenes from your father’s childhood in a refugee camp with your grandparents. How did the images of children shape this book?

Many of the poems are dedicated to the lives and the memory of children who were killed during the Israeli attacks. There’s the poem titled “The Moon,” about the girl who was killed in the street with her father while trying to run away from the bombardment. There was also the girl who was buried under the rubble of her house [in “Right or Left!”]. We were [only] able to retrieve her body after [several] months, and we only found her arm. What we have been going through is something that starts from a very, very early age. I can tell you about thousands of children, especially during this genocide, who were born and killed during the past ten months. These are children who didn’t even have the chance to know where they were born. I was born in 1992, and the last elections were in 2006. I did not have any chance to elect or vote for anyone. Anyone who is thirty and younger never had the [right] to vote. So, what about the kids? [Almost] 50 percent of the people in Gaza are under the age of eighteen. They did not vote for Hamas or any other faction. I’m talking about kids who were born and killed before even getting out of their houses. And here I should mention the twins [Asser and Ayssel] who were killed in an air strike [with their mother, Joumana Arafa, and their maternal grandmother] six days ago. Just imagine, not only were you caring for twins, but you also had a C-section just days before the air strike. What was the mother doing when the air strike happened? Was she breastfeeding? Did she even have enough [milk] to feed her children? There are so many questions that people don’t pay attention to. They just know a mother and her twins were killed. They don’t [necessarily] think about what was happening before the air strike. That’s what I care about as a human being, as a poet. I care about the moments before the death. So, children are in the book because most of the people who are killed are not only children, but they are toddlers and infants, sometimes even fetuses in their mother’s wombs. Children populate my poetry as much as children populate the scorched land of Gaza.

Your poetry is an unwavering depiction of the violence Palestinians have suffered during this present war as well as in the past, but there is beauty in your work too. You describe families and communities banding together, sharing scant resources, and keeping one another safe. The rich history of love and community in Palestine is something that shines through. How has that history influenced your work?

What the occupation is doing right now in Gaza—more than 70 percent of the buildings have been either destroyed or damaged—is they are wiping out everything that reminds us of what home was like. In the U.S., I can see buildings that are two hundred, three hundred years old. I can see trees that are older than my grandfather. You as an American poet can, in a few years, come back with your child, or your nephew, or your niece, and show them the school where you went, the tree where you used to play on the swing, the river where you used to swim. You can show them the church, or the mosque, or the synagogue where you and your parents used to go to pray. You can go to these places. The toys you had, you can pass to your children or your neighbors’ children. But what’s happening in Palestine and now in Gaza in particular is not only killing our loved ones, our students, our neighbors. It’s also killing the city. We are losing everything, but we are not losing the memories that we have of these places. So when I tell my children and my grandchildren about the city I was raised in or about the neighborhood where I grew up, when I tell them about the mulberry tree and the farm where their grandparents planted orange trees, olive trees, guava trees, I’m helping them re-create this place in their imagination. I do what I can, sometimes against my will, because I want to rest. I wish this did not happen. I wish there was no occupation. I wish I didn’t have to write poetry about death, or loss, or fear. I wish I were Robert Frost, tending to some trees in the countryside, writing about the trees, cattle, birds, and rivers. But, no, I’m writing about similar things being destroyed and taken away—beauty being perished.

I’m glad you mentioned Frost because several poems in both of your collections are “after” poems, written in the tradition of Wanda Coleman, Audre Lorde, and Allen Ginsberg, among others. Can you talk about how non-Palestinian writers have influenced your work?

As a poet I am part of a long line of writers who have found themselves reflecting and reporting on how they are treated and how they see other people like them being treated. Yesterday I was reading Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” The white judges called him an outsider to the city, but [King] said injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. The injustice that’s prevalent in the United States in the past and in the present is a threat to justice everywhere. The injustice that’s prevalent in Palestine is a threat to justice everywhere. And we see injustice everywhere. There is no justice in any place, except for a select minority of people who create their own justice by oppressing others. When I read Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg, Audre Lorde, I feel like I’m responding. I see myself as part of this line of poets because I’ve been deprived of my rights as a human being. I’ve been dispossessed. My grandparents lived as refugees until they died, and I’m still a refugee. The experience of the Palestinian people is just like the experiences of Black people, of Native American people. They are treated as outsiders, even on their own land. When I read works by Indigenous people and oppressed people, I relate to their work and I feel like I’m continuing their work. My work is part of their work, and their work is part of my work. We are chanting against the same set of oppressive regimes.

As a poet, a father, and a human being, what brings you joy these days? What gives you hope?

The only joy I find is when I can write about something indescribable. I find joy when I finish because I’m doing something not for myself but for other people. And hope? Hope is a noun. And the verb form is to act. Wherever people do not remain silent, I see hope, because as long as we continue to shout and scream, things will change. Many people believe [what is happening] is unjust and inhumane, but they are afraid to share these opinions. But when you do this, and I do this, and my neighbor does this, and my schoolteacher, other people feel encouraged to speak up.

In Gaza I see hope in the people, not sitting in their tents but running here and there to feed their families and offer help to their neighbors. During times of war you see people attacking each other, stealing from each other. But what I see is people trying to support one another by installing potable water stations, offering food, and raising funds to offer to poor families. I see hope in people not only caring about themselves, but also offering support to others around them.

What can writers—particularly non-Palestinian writers—do in response to what is happening?

What I’m thinking right now as I’m answering your question is that anyone who calls themselves a true poet should think of collaborating with other poets in their community and work on writing the longest poem in history. Everyone can sign up for this, and there is a name for it: the renga. Each poet could contribute two lines based on a picture or a feeling they had watching and witnessing what has happened in the past [year]. They don’t have to sign their names, and it could be anyone who wants to write poetry, because poetry is not about poets. It’s about everyone who can express something. And it’s not only about retweeting or re-sharing what other poets, writers, and activists in Gaza are posting. It’s not enough to witness. It’s also good—it’s important, it’s imperative—to take a stance by writing what you see. Everyone should ask themselves what they can do to respond to my writing, to other people’s writings, to other people’s art. Witness, whether by responding to what you read and sharing it with other people, or by offering your own insights into what you are witnessing. If we can write this long, long poem, the generation that comes after us will know that we did what we claimed to be.

Destiny O. Birdsong is the author of the poetry collection Negotiations (Tin House, 2020) and the triptych novel Nobody’s Magic (Grand Central, 2022). She is a contributing editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.