In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 163.

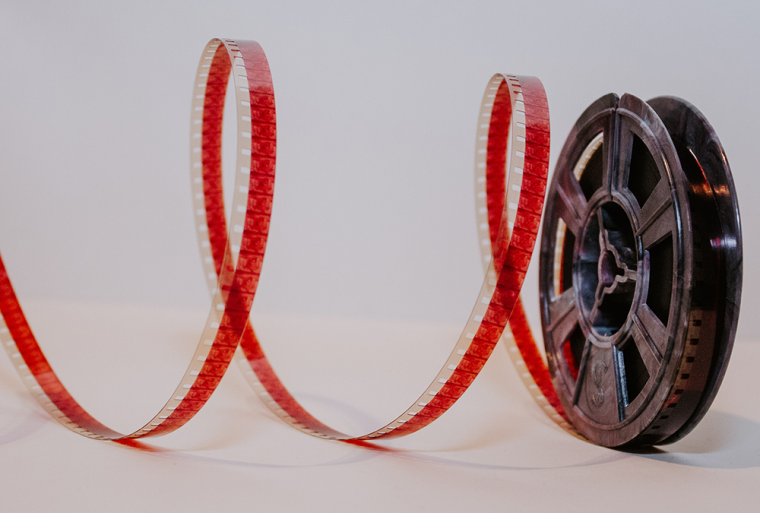

When I hit a wall in my writing—poetry, prose, or hybrid work—I realize that the approach I’m taking needs to be disrupted. Instead of pushing against the wall, I must break it down, dismantle the structure, and rearrange it. I become reenergized by the process of rearrangement via disarrangements of the intended or expected sequence of words, images, and sounds. An image: taking a razor to a strip of celluloid film, a fragment falling onto a table filled with scraps of potential scenes—an accidental epiphany from a renewed perception of the mass of discards. I do not physically cut up the page I’m working on, but rather return to discarded drafts or archived notes to renew my vision of it. Because I once saw these old documents as superfluous, I am able to deform them by digitally cutting them up, splicing their images, language, and insight in order to direct the new piece to an uncertain destination. Yet this uncertainty, this surrender to what John Keats calls “negative capability,” is how I move with the text rather than force it into my original intention. In other words, in the process of rearrangement, the initial intention of the writing—its promise of clarity—recedes as the impulse of association takes hold. When I say I become energized by the process of rearrangement, I am saying that I realize the need to abandon intention and surrender to accidents of slippage and contagion: the failure of certainty.

I recall essayist John D’Agata’s claim that if “we take to heart the traditional idea of the essay as an attempt to figure something out—an attempt, but not a guarantee—then the essay is also inevitably an apprenticeship with failure.” When taught how to write a formal essay in school, we’re taught the formula of introduction, body, and conclusion. We’re taught that the success of the essay depends on its organization and clarity. We’re taught to provide evidence to substantiate our claims. We’re taught that our process of “figuring out” needs to be evaluated in the form of a grade. We’re taught how to write against failure, against the possibility of not being understood. We’re taught to replicate procedure. But the essay should be an experiment—without a guarantee of success, like the hypothesis before an experiment. In the essay-as-experiment, however, the scientific process is stalled and undergoes hypothesis and experimentation dialectically. The essayist, as Theodor Adorno writes in “The Essay as Form,” is “discontent with the procedure [of the scientific method].”

In the Introduction to Creative Nonfiction class I took as a sophomore creative writing major, I remember the feeling of excitement when encountering fragmented essays in Brevity: A Journal of Concise Literary Nonfiction, the nonlinear narratives of Joan Didion’s The White Album, and the elegant randomness of Sei Shonagan’s The Pillow Book. It was in this class that I learned that the word essay originated from the Middle French essai, meaning an attempt. Rather than analyzing how authors reached their arguments and the validity of their claims, we studied the essay as an experiment in thinking, which invited contradiction and imagination. It was in this class that I first learned how to let memory stand as a scene rather than try to explain what it meant or how I felt about it.

For my final project in that class, I wrote an essay called “Allegiance,” which I see now as the genesis of my first book, Mistaken for an Empire: A Memoir in Tongues. In “Allegiance,” I juxtaposed memories of my life in the U.S. with my life in the Philippines alongside memories of my mother and grandmother. It was a study in ambivalence, a working through of complicated parallels between my dual citizenship and the expectations of choosing one maternal figure over the other in the face of familial conflict. After submitting “Allegiance,” I let it sit in my computer’s documents folder and moved on. Later, in my MFA program at the California Institute of the Arts, I rediscovered the essay while stuck on a draft for what is now Mistaken for an Empire. After cringing at certain stylistic choices and moments in which I made cliched connections between personal and national concerns, I began to highlight, cut, erase, and copy the text of “Allegiance” into my then-current draft. What was once a finished essay was now a receptacle of scraps that could be recycled into something less like an essay and more like a montage.

I was deeply inspired by Sergei Eisenstein’s concept of the montage while writing Mistaken for an Empire. In “A Dialectic Approach to Film Form,” Eisenstein defines the montage “as an idea that arises from the collision of independent shots—shots even opposite to one another.” Thinking of my book as a montage refused a hierarchization of materials and any desire to suture contradiction with explicative narration. In allowing this collage-like method to dominate the writing process, a hybrid form emerged wherein memories, documents, photographs, advertisements, and poetry all comingled, like a montage of images that spoke to the ambivalent tension of living a hybrid identity.

Hybridity itself can be understood as a type of failure, a failure to remain pure and authentic, a failure to define oneself legibly and singularly. Writers of hybrid identities—such as first- or second-generation immigrants, who balance the expectations of multiple cultures—often feel inauthentic, unable to meet any one culture’s standards. In her essay “Multiplicity from the Margins: The Expansive Truth of Intersectional Form,” Jen Soriano puts it this way: “This clash of internal multiplicity and external expectations of a single truth yielded one definitive result: my silence.”

Maybe, then, the writer of the hybrid essay is not simply an apprentice of failure, but kin. Hybrid forms fail to fit into the box of genre and follow generic conventions. To fit into these forms is a silencing of difference, a silencing of what fails to be understood by the dominant culture. Positioning hybridity as failure does not mean it is lacking in rigor or technique, but that it resists being categorized. In “The Queer Art of Failure,” Jack Halberstam writes, “The concept of practicing failure perhaps prompts us...to be underachievers...to lose our way...to avoid mastery.” When I say the writer of the hybrid essay is failure’s kin, I mean that the writer is able to surrender to the uncertain paths of experimentation in order to find new ways to articulate herself. Writing my book as montage, I risked the failure of being understood by everyone for the prospect of remembering the histories and people erased by the continued legacy of imperialism, while also calling attention to moments of inscrutability, resistance, and excess. When one writes with failure as kin, one writes without the expectation of understanding, ceding to the persistence of the opaque. By relinquishing the goal of being understood, one gains the freedom to dismember, fracture, and play.

I return to the beginning of my essay: “The renewed perception of the mass of discards” cannot simply be an epiphanic moment of aesthetic possibility, it must be a reckoning with fraught associations; it must be a failure of forgetting. That is what I am doing when I find myself stuck during the writing process—resurrecting what would have otherwise been forgotten.

Christine Imperial is a PhD student in cultural studies at the University of California in Davis, where she was awarded the Dean’s Distinguished Graduate Fellowship. Her first book, Mistaken for an Empire: A Memoir in Tongues, won the 2021 Gournay Prize from Mad Creek Books, an imprint of Ohio State University Press, where it was published in April. Her work has appeared in American Book Review, Inverted Syntax, Poetry, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the California Institute of the Arts.

Art: Denise Jans