In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 123.

When I (ill-advisedly) joined Twitter in 2016, I often scrolled through an account dedicated to images of nonliving things that appeared to have a face. A smiling banana slice, for instance. Or a frowning toaster. Or a surprised-looking cottage. None of these things were intentionally designed to look like a face, but once a viewer like me registered a pair of eyes and a mouth, the face was impossible to unsee.

I perused these images to amuse myself, but actual scientists have studied this face-perceiving phenomenon. Called face pareidolia, it is a product of evolution. We see faces where faces are none because our brains constantly scan for people—specifically for the presence of friends or foes. To search for people—then plumb their expressions for meaning—is an inherently human impulse.

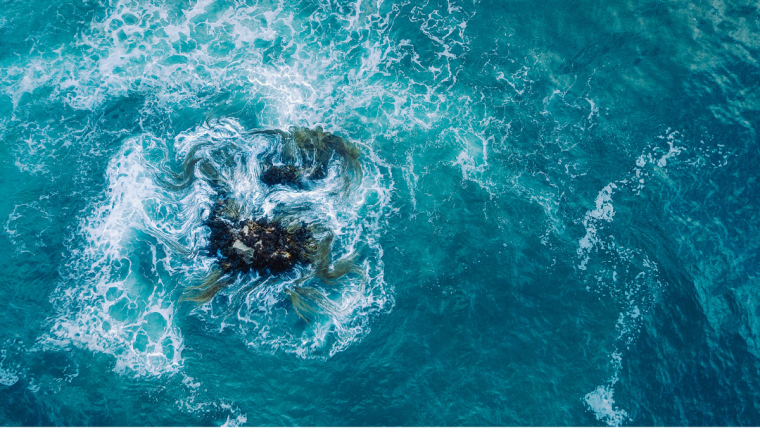

It is also a literary one. Folklore and mythology across cultures are full of surreal faces. Volcanoes, trees, lightning storms are given consciousnesses, if not outright god-formed representation. Take Scylla and Charybdis, who appear in The Odyssey as a multi-headed cave dweller and toothy whirlpool, respectively. They are characters in the story—monsters who give Odysseus a hard time—but they also embody a real place: the Strait of Messina, which separates Italy and Sicily. This channel was once deadly for sailors because of its rocks and whirlpools. Applying faces to the waterway helps depict the experience of moving through a dangerous landscape.

Rendering the Strait of Messina into characters also serves the overall narrative. If Odysseus had merely struggled with ocean currents and rocky cliffs, that would not have been nearly as exciting as seeing him face a pair of characters with their own goals, stakes, and personal histories. A setting with a face has something to gain or lose; it can have an emotional reaction to changing circumstances. Readers can better recognize the dynamic relationships between people and the world they move through. After all, we affect our environments, just as they affect us. There is no way to truly leave no trace on our world, nor can we remain uninfluenced by our surroundings. Thus, when Scylla howls after being tricked by Odysseus, we register her rage as a part of this truth.

For contemporary fiction writers—even those not working in overtly magical or fantastical modes—I’d argue that there is much to be gained from embracing the human impulse to see faces where faces are not really there. A recent novel that demonstrates such narrative benefits is Alexandra Kleeman’s Something New Under the Sun (Hogarth, 2021). In the universe of the novel, synthetic water—or WAT-R—has become ubiquitous in California. As this artificial substance leaks into the landscape, its ecological and meteorological permutations are often described in personified terms that give aspects of the setting an animate and sinister quality. Take this description of clouds formed from evaporated WAT-R: “They remain still and quietly watching, waiting for their moment to approach, waiting for their moment to show what they really are.” Setting, in this instance, is given a human-like motive, which heightens the drama of the overall description.

Kleeman breaths humanness into other descriptions of setting as well. A starlet’s mansion is “half-living, multi-lunged and plushly organed, steeped in electricity and suspended in a continual sigh.” And though these household functions are “too massive, too slow, for any real creature,” a reader registers the animacy and near-consciousness of the home. It seems to breathe. To think. To live. This is a setting that could, perhaps, feel. There are stakes around the mansion’s existence, so when something happens—say, the house burns down—the sense of damage reverberates outward, not just for what was lost, but for who. And in the long hallucination that is lived human reality, whether there was ever actually a character there, a person—a face—is less important than how this lens helps us navigate the world and tell the stories we need to tell to survive.

Allegra Hyde’s first novel, Eleutheria, is forthcoming from Vintage on March 8. Her debut short story collection, Of This New World, won the John Simmons Short Fiction Award through the Iowa Short Fiction Award Series. Her writing has also appeared in numerous publications, including American Short Fiction, Kenyon Review, and Tin House. Born in New Hampshire, she lives in Ohio and teaches at Oberlin College.

Art: Francisco Kemeny