Barbara Gowdy and Helen Phillips are masterful investigators of the what-if. In their award-winning fiction, they dip into the surreal and the speculative just enough to tell the truth—about the strangeness of our present world, the permeability of the psyche, and what binds us as humans. It’s weird, wonderful work that gets people talking. Phillips is the author of Some Possible Solutions (Henry Holt, 2016) and The Beautiful Bureaucrat (Henry Holt, 2015), and has been called by NPR “an uncompromising author as unique as she is talented.” And Gowdy, the international-bestselling author of The White Bone (Metropolitan Books, 1999), Helpless (HarperFlamingo, 2003), and other novels, is celebrating the release of her eighth book, Little Sister, from Tin House Books this month. In Phillip’s words, what captivates her about Little Sister is the way it “unveils the alternate possibilities hidden within the everyday.” It’s the story of a sensible cinema owner named Rose who suddenly finds herself inhabiting the body of another woman, Harriet, whenever it storms. The novel that unfolds is, according to Publishers Weekly, “a thrilling, captivating exploration of guilt, the female psyche, and the bonds of womanhood.” It is the latest example of what Gowdy and Phillips both do so seamlessly—the kaleidoscopic turn from the slightly off-kilter to our deepest, realest truths.

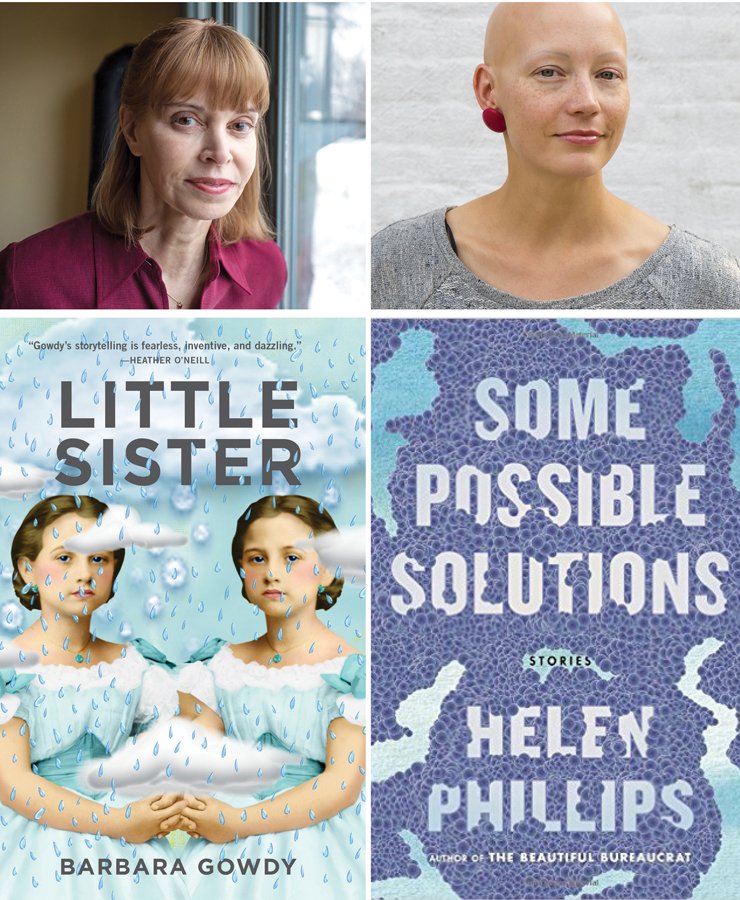

Barbara Gowdy, whose novel Little Sister is published this month by Tin House Books, and Helen Phillips, author most recently of Some Possible Solutions (Henry Holt, 2016). (Credit: Gowdy: Ruth Kaplan; Phillips: Andy Vernon-Jones)

The following conversation took place between Helen Phillips and Barbara Gowdy over e-mail this past winter. What started as mutual admiration became a deep-dive into profound empathy, how literature can change women’s relationships to their bodies, and writing against the odds.

Helen Phillips: Little Sister is at once suspenseful and introspective. The bizarre condition affecting Rose, as well as the dark backstory about Rose’s sister, had me on the edge of my seat, as though I were reading a thriller. But the overall tone of the book is thoughtful, measured, contemplative—not the fast pace we typically associate with the idea of “thriller.” Even when we get the first hint of the surreal, it takes the subtle form of Rose’s vision becoming slightly more acute. I love the interplay of the everyday with the extraordinary here. Did you think much about the idea of genre as you were writing the book? Were you deliberately seeking to contrast the tone with the plot?

Barbara Gowdy: Right from the start I had only one idea, and that was, “What if a woman were to find herself inside the body and mind of another woman?” As it happens, I read your new short-story collection, Some Possible Solutions, a few days after I finished the editing process, and I was greatly relieved that we didn’t cross narrative paths, because I was really taken with your book, and you and I are both attracted to metaphysical scenarios concerning identity and the body. Like you, I wanted the impossible to seem possible, to be just at the edge of what we know to be true. That’s why I tried for a practical, everyday tone, which I labored over—how to be clear without being instructive. And actually, no, I never thought about genre, not until now. But I’m more than happy if Little Sister comes across as a thriller.

Phillips: “Metaphysical scenarios concerning identity and the body”—yes, a central concern for both of us (and thank you, by the way, for reading my book). I suppose it’s no surprise that I was drawn to your interplay between the possible and the impossible, between the mundane and the supernatural. And actually your response brings me right to my next question. I thought a lot about the female body as I was reading Little Sister. In the book, Rose literally inhabits Harriet’s body, experiences a body altogether different from hers—different, most significantly, because it is fertile. A great deal of societal pressure is exerted on the female body—as sex object, as possession, etc. Women often feel competitive about their bodies, defensive of their bodies, uneasy in their own skin. Here, though, Rose has the opportunity to feel solidarity with a female body other than her own, to feel protective of it. What are your thoughts about how putting a female inside another female’s body colors both women’s relationships with their bodies? How does this enrich and/or complicate their identities?

Gowdy: My own relationship with my body was fraught, I can tell you that. I didn’t mature physically until I was almost sixteen. I was scrawny and boyish, which wasn’t a fashionable look back in the mid-1960s, when Raquel Welch was the ideal of female beauty, or at least she was in my family. I once overheard my father ask my mother, “When is Barbara going to develop?” (i.e., grow breasts), and my big-breasted mother say, “Don’t blame me. Those are your genes.” I wore the thickest padded bra you could buy, and three pairs of underpants. I’m sure that this massive insecurity led me to write about bodily transformation and unease in several of my books, and that I ended up writing about a woman escaping into another woman’s body as a kind of catharsis. Although I should add that Rose, the escapee, is fairly comfortable with her looks. And while she is initially frightened by her visits into Harriet, she becomes more and more fascinated by the differences in circumstances, eyesight, altitude, touch, nervous systems, temperaments, feelings, and all the rest. It surprises her, for example, that a woman as slim, pretty, and professionally successful as Harriet should suffer from extreme anxiety. So Rose is enriched by having this singular opportunity of measuring her own anxieties, her own experience of being alive, against someone else’s. Would that we were all able to have such an opportunity. I mean, imagine if the world’s tormenters were thrown into the bodies and minds of the people they torment. Or if a miserable wife were able to enter her miserable husband, and vice versa…any combination: if Kim Kardashian entered a Maasai cattle herder. If I entered you.

Phillips: Yes, the book ends up being something of an experiment in profound empathy. Walking a mile not in another man’s shoes but in another woman’s body! As long as we are on the theme of bodies: I’m intrigued by the way that Rose’s transformations are inextricably connected to the weather. I read it as suggesting that the human body and weather patterns are both natural forces whose power is often underestimated—was it your intention to draw that connection between the two? Why was extreme weather your chosen device?

Gowdy: In an early draft I had Rose enter Harriet after swallowing a powder, mistakenly the first time, deliberately from then on. But this made her something of a stalker. Better, I thought, to have her entries be beyond her control, so that the ethical implications of secretly wading around in someone else’s body and mind don’t become a huge issue. I went with the weather as an instigating force because, as you say, it’s big and natural. Also, it’s electrical; it affects our brains.

Phillips: The interplay between the present time of 2005 and the past of Rose’s childhood feels rich and mysterious to me. The different time periods are somehow connected, but the lines are blurry. How did you go about evoking a character at different life stages, in different time periods? What were the challenges of capturing young Rose and grown Rose?

Gowdy: I return to the childhoods of one or two of my main characters in most of my books, I think. It’s nothing I plan on doing ahead of time, but I guess it’s as if I need to establish certain propensities in the child before I can fully create the adult. And then there’s the joy of writing about children because they haven’t yet formed a shell sturdy enough to hold in their souls. Children are so expressive and hilarious. They’re all poets in that they’re trying to get a fix on the world, so they’re comparing everything to everything else, sounding out words, taking what you say too literally, even as they believe in magic. I hope the young Rose is recognizably the grown Rose, but neither is quite the other, and that’s where I live as a writer, in the place between the living, personal self and the remembered self. Or in the place between the living self and the different self.

Phillips: “Living self” and “different self” could also describe the relationship between Rose and Harriet. And I must agree with your description of children as natural poets—I have two young children, and their reliance on metaphor to describe what they don't know always surprises/delights me. On another note: As mentioned in my first question, this book hits multiple different notes, and it makes me wonder what you would consider your literary (or otherwise) influences for this book, and/or what you were reading while you were working on it?

Gowdy: When I was in my early twenties I read Daphne du Maurier’s The House on the Strand. It’s about a guy who willingly acts as a guinea pig for his scientist friend and takes a drug that sends him into the fourteenth century, where he can move as a ghostly presence in and around people’s lives without them being aware of him. I was enraptured by the intimacy this afforded him, his ability to eavesdrop on conversations and to watch people when they assumed they were by themselves. I’m not a sexual voyeur, I promise you! But I’m endlessly curious about how people live their lives. Which is something Rose, of course, has unrestricted access to when she’s inside Harriet. Well, not quite unrestricted: She experiences Harriet’s senses and emotions, but she can’t quite penetrate her thoughts. Anyway, that book, The House on the Strand, was certainly an influence. Other books influenced me stylistically. I read all of Penelope Fitzgerald and greatly admired her economy and precision. I read James Salter and loved him for the same reasons. I recently read Salter’s wonderful The Art of Fiction, in which he praises the writing of the early twentieth-century Russian novelist Isaac Babel for being both unobtrusive and staggering. Now there’s a combination to aim for.

Phillips: I’m also curious to hear the story behind the story—what was your process for writing this book? How long did it take, etc.?

Gowdy: Oh, God, it took ten years! I wrote very little else. With my partner, Christopher Dewdney, I wrote a screenplay nobody wanted. There went nine months. I wasn’t blocked with Little Sister, the problem wasn’t a brick wall, it was that I have chronic back pain, and many days during those ten years were spent seeing doctors and alternative therapists. Meanwhile, I was going on and off painkillers. When I was on them, I was usually too wired or cloudy to write. When I was off them, I could write. It was either pain or brain. I hope this doesn’t sound whiny. It’s just how it was for me, and still is, and we all have something to get through. As for my process, I rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, sentence after sentence, draft after draft. I’m rarely more than a phrase ahead of myself.

Phillips: I’m so sorry to hear about the physical pain that ran alongside the writing of this book. But I have to admit that in a strange way I’m not surprised. There’s something so deeply physical about this book, something in it that’s getting at the heart of what it means to have a body and a mind, and the ways that body and mind can be at odds and in harmony. Is there any advice you might give to writers struggling with physical or mental challenges?

Gowdy: Twenty-five years ago Leonard Cohen, who was prone to bouts of depression, said that if you stick with it long enough, it will yield, the miracle will come. He also said, “Long enough is way beyond any reasonable expectation of what long enough might be.” He was referring specifically to writing song lyrics, but surely this applies to all creative work. Keep going, have faith, regardless of your circumstances, regardless of your pain or poverty. You’ll get there eventually. I believed him then, and I believe now, and I can’t think of better advice.