Submit yourself to the uncertainty and mystery of it all,” advises Darius Atefat-Peckham, one of the ten authors spotlighted in our twentieth annual debut poets feature. Of course, verse has always been known to have an enchanting quality, a certain, or not so certain, je ne sais quoi. Poetry often moves beyond the concrete physical realm in slippery and nebulous linguistic ways, refusing to be understood in its entirety through sheer intellectual prowess alone. This year’s feature rather ceremoniously includes writers who keep to this wondrous definition of poetry while reaching further still. In the “mystery of it all” that these books both dig into and surrender to, they provide a landing place for our sorrows and deepest ruminations, a salve for our earthly and psychic wounds.

Clockwise from top left: Kenzie Allen, Jimin Seo, Sarah Ghazal Ali, Diego Báez, Saretta Morgan, Yalie Saweda Kamara, Darius Atefat-Peckham, Stephanie Choi, Christian J. Collier, Matthew Gellman (Credit: Eugene Smith)

These are collections that spring forth from the inquiry, “What is poetry next to death?” with ensuing poems written in the voice of a late mother and friend (Jimin Seo’s OSSIA), to call them back, to be near. Within them lamentation becomes hard-earned and tender wisdom (Christian J. Collier’s Greater Ghost) and grief reveals the strong undercurrent of love beneath it (Darius Atefat-Peckham’s Book of Kin). These collections were carefully and painfully molded, as if through back braces, headgear, and expanders screwed inside a small but mighty mouth (Stephanie Choi’s The Lengest Neoi). They whisper in your ear about the shards of a queer childhood (Matthew Gellman’s Beforelight), pray in Victoria’s Secret fitting rooms (Sarah Ghazal Ali’s Theophanies), where faith becomes “feminine, breasted / and irregularly bleeding.” These are collections that are international and rooted in hometowns (Yalie Saweda Kamara’s Besaydoo), that speak of colonialism, distance, and understanding the multifaceted self in three distinct tongues (Diego Báez’s Yaguareté White). They break ground, excavating personal and collective histories (Kenzie Allen’s Cloud Missives), and conjuring a desert landscape that aches as the body aches, nature that loves as the body loves (Saretta Morgan’s Alt-Nature).

In their replies to our questions, these poets astutely remark on their literary journeys to date, some of which included almost fifteen years of writing and rewriting a manuscript, while for others it took three months to find a publisher. Despite their varied paths to publication, they commonly advise not rushing into getting a book published and aiming high while focusing on presses that understand your unique vision and can introduce your work to the world in a way you see best fit, though “the caterpillar phase is wearisome,” Kenzie Allen is careful to add. In marking the two decades this magazine has spent celebrating emerging poets, we have ten writers who remind us of poetry as illumination, alchemy, medicine. Poets who prove that care—deep attention to all beings (of the past, present, and future)—is still the greatest connective tissue binding us all, invisible though it may feel at times, and that it can still unite author and reader in word and thought and, yes, spirit. As Matthew Gellman writes, “Poetry was a means of having an intimate, private conversation with my most inward self, but it also served as a gesture outward, a bid for connection and understanding from other people.”

Kenzie Allen | Jimin Seo

Sarah Ghazal Ali | Diego Báez

Saretta Morgan | Matthew Gellman

Christian J. Collier | Stephanie Choi

Darius Atefat-Peckham | Yalie Saweda Kamara

Cloud Missives

Tin House

We tipped our throats to night showers

and tried to lick back stars the city had obliterated,

to resurrect anything at all by taste,

their glittering signs and warnings.

—from “Light Pollution”

How it began: I wanted to find a way to speak to what felt unsayable at the time, to name the violences I’d experienced, to uncover the personal and cultural memories that had been buried, and to commemorate the connections I’d made with the world around me. Poetry affords the creation of new vocabularies—new ways of naming things—and ways of interrogating what might be mysterious or elevating that which might otherwise seem commonplace. I wanted to make my own language through the writing of these poems, and then recognize and cultivate the stories that emerged as the pieces were set in proximity. I wanted to write back against stereotypes and misconceptions of Indigenous peoples, to use this new language, alongside the influence of oral histories and lived experiences, to reclaim culture, identity, and survivance.

Inspiration: Anthropology has always been a source of fascination and inspiration for my work. Anthropology and archaeology are their own kinds of storytelling, where the observer pieces together meaning from remains and evidence found in excavation. That’s poetry, too, isn’t it?

My parents are certainly guiding forces—my mom on the Indigenous side, and my dad, a biologist and fire lookout. There’s flora and fauna in both of those worlds, ways of knowing and ways of being, pow wow dance styles and traditional medicines, learning each peak and valley of the horizon by heart, caretaking the land, reading the earth as its own literature. My dad can name every kind of cloud. My mom teaches me and reminds me to move in good ways.

I also like to surf Wikipedia articles via the “Cool Freaks’ Wikipedia Club” Facebook group to find subjects to explore, particularly those that are multifaceted or taxonomic in nature. The crab love poem [“Convergent Evolution”] in my book is a direct result of this kind of cruising for categorical knowledge, in this case “carcinization,” or how so many things seem to want to evolve into crab-like shapes. And then I layer these subjects with news stories, memory, emotion, or imagined experiences.

There is also those kids books with the see-through pages that show, layer by layer, the inside of the human body or a beehive or a bird’s egg. I think that, alongside my excavatory impulse, led to my interest in interior and exterior forces.

Influences: Pattiann Rogers, Stephen Dunn, Roberta Hill. There are so many I could name, but these three are some of the writers I turn to when I need to be soothed by the capacity of poetry to evoke love, grief, ways of knowing. Rogers inspires me toward reverence, Dunn offers lifelong wisdoms, and Hill is a beacon whose “[h]ouse of five fires” raises me up.

Writer’s block remedy: Sometimes I’ll smudge or say the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address before sitting down to write, particularly when I’m working on a difficult poem or through a tangled emotion, or when I just need to honor the land beforehand. Writing is its own kind of ceremony or medicine, but I find that turning to Oneida ways of knowing helps keep me grounded.

Mainly I tend to switch modes and mediums as needed, which helps me return with new perspectives later. It also means I don’t think about things in terms of writer’s block—getting stuck is just a sign I need to pivot for a moment; it’s more of a squeaky wheel than a barrier. And sometimes I just let myself be, rather than pushing the issue. I’ll continue to observe and mentally work through ideas, but the brain needs its own pivot points and its own time to marinate, so I recognize the fallow periods as an important part of the process too.

Advice: It can be helpful to have more than one project going. If what you initially sent out isn’t the right fit but they like your writing, you might be asked to send more work in the future. In my case, since I’d sent out what was really more of a second book, I asked myself, “How soon is the future?” and I already had something (the “first book”) ready to send right away.

It’s also okay to take your time. There can be such pressure to put out a book right away—there are job ads open only to those who have “emerged” (and the “emerging” contests can feel like an endless merry-go-round). There’s some sense of a ticking clock with the proliferation of “30 Under 30” lists and so on, and in general the caterpillar phase is wearisome. But it’s really wonderful when you find the right press and you’ve spent all that time polishing your manuscript until it can’t help but shine. Of course, you don’t have to be fully at that stage before sending it out. A great editor is an invaluable influence, and it’s good to stay open to what the book could yet become.

Finding time to write: I’m still working on this, but I’m constantly writing in some form or another. I will absolutely interrupt a conversation to take notes. Or I’ll write in the shower (on waterproof paper). Or during a family outing. Anywhere an idea hits. It’s ruthless. And I like to write when I’m out in various landscapes, so I do a lot of walking and writing. This means, of course, that I need to change up my surroundings every so often so that my environmental influences also shift. You can only write about the same type of bird so many times. But the brain is always making its connections, searching for narrative, juxtaposing what it sees and what it remembers. We’re always writing even when we’re not. We’re percolating. And we just need to remember to stay active about it. Go on and feed the cauldron.

Putting the book together: Once I’ve gotten a manuscript to critical mass, I tend to print out the whole stack of poems and tape them up on the wall, on what I call my “poetry murder board.” In the movies when you see one of those walls of pictures and sticky notes, with colored string linking all the components together, that’s supposedly called a “murder board.” I haven’t progressed to the string bits yet, but I use the sticky notes and a pencil, and I move poems around to see how they speak to one another and where the gaps might be. For me, it’s not enough to just stare at a manuscript on my computer screen. I’ve got to live with the poems for a while, to inhabit the same room and be faced with their overall shape.

For the last few years Cloud Missives was up on a wall that you could see from the street in front of our house. It must have looked…concerning. I finally took all the poems down the other day, and it was such a big shift—the whole room felt alien and empty. I wondered if it was just as disconcerting for anyone else that the pages had suddenly disappeared. But the wall never stays bare for long.

What’s next: I tend to have multiple projects going at any given time. Right now this includes a multimodal manuscript about the transnational journeys of generations of my Oneida family, a memoir-ish collection of poems about matriarchy, and a follow-up to Cloud Missives currently titled “Diary of Belief.” I have a couple prose projects, and I’m also learning how to be a mom.

Age: 38.

Residence: Toronto.

Job: I’m an assistant professor in Indigenous literatures and creative writing at York University.

Time spent writing the book: Over a decade. Some were written in 2011, some in 2024. All were revised through the editing phases of book production, often with new material.

Time spent finding a home for it: Seven years in some form or another. Three years in its current form.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: I’m excited for the wellspring of Native poetry coming out right now: m.s. RedCherries’s mother (Penguin Books), Kinsale Drake’s The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket (University of Georgia Press), and Amber McCrary’s Blue Corn Tongue (University of Arizona Press, 2025). As well as Raye Hendrix’s What Good Is Heaven (Texas Review Press), Sarah Ghazal Ali’s Theophanies (Alice James Books), Ae Hee Lee’s Asterism (Tupelo Press), and Saba Keramati’s Self-Mythology (University of Arkansas Press).

Cloud Missives by Kenzie Allen.

![]()

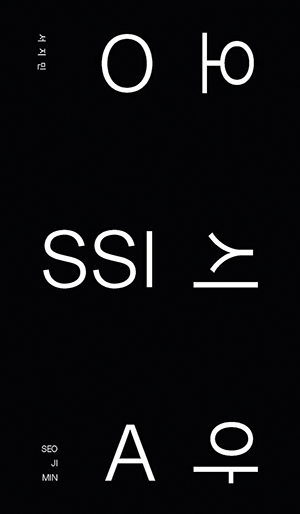

OSSIA

Changes Press

(Changes Book Prize)

I bless the knife that skins the fawn from its

mother’s field. I bless the fat between the

hide, the flesh, ignites. I bless your dream,

its bullet caught in the poet’s bite.

—from “OSSIA”

How it began: I wasn’t able to build poems in my own voice after my mother’s death in 2013, so I stopped. I mean my poetry voice stopped. It could only ask me: What is poetry next to death? Still, during the pandemic silence I began to build poems in my mother’s voice. That same year I found out my friend Richard Howard had dementia. When I called him on the phone, he forgot who I was, and I became desperate. I reanimated Richard’s voice in dramatic monologue (to me, always his form), to remember, to have him talk to me. I was in a kind of mania, I think. It still feels selfish to reanimate my dead and transfigure them into a book. After all these years what can I miss? Memory? The mooring of this book was to show Richard and my mother I was writing again. I failed to show them any achievements (merely being alive didn’t count) during their lives. I was running out of time. And time did run out. This is a book of loneliness and regret.

Inspiration: My friends and fellow artists were a great source of comfort. Rebecca Hazelton, Asa Drake, Nicole W. Lee, H.Sinno—they gave me a reason to keep writing when I wanted stop.

Influences: I was training to become a classical pianist before I became a poet. I gave myself nerve damage in my right index finger and there was poetry, waiting. Accident led to accidental poetry technique class and here I am. That’s a long way of saying I draw most of my inspiration from classical music and musicians. I love how musical forms are conjured relationally in poetry. As a failed musician, I conflate the interpretation of music with poetic practice. You can have so many interpretations for one piece of music, and I find those minute variations in approach hugely influential. And because so much of the critical writing on poetry uses the lexicon of music and music-making, I learn a lot from music and literary criticism. Edward Said’s writing on music—a favorite, Musical Elaborations (Columbia University Press, 1991)—is a boon. As are the forms of conjuring in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s performances, Bach’s fugues, Schumann’s Études symphoniques, and Gershwin’s The Man I Love played by Isata Kanneh-Mason.

Writer’s block remedy: I write in intense bursts. Something like three months of the year, from 10 PM to 5 AM. I think the most interesting things happen when you’re at the bottom and it feels like there is no way out. But then again, this is my personal practice. I put myself in crisis and dig myself out. I don’t recommend it! Joking aside, I think it’s useful to know how you work and to honor and tweak that as it comes.

Advice: A draft of a manuscript doesn’t have to be perfect; it just has to work. One of the most valuable lessons I learned from music was recognizing what a finished work sounds like. A poem can be good or bad, and in the span of organizing poems into a full manuscript, how these good and bad pieces resonate with one another informs a working, breathing organism. Don’t worry about the value of a single poem. Try to recognize the manuscript wholly—send it out.

Finding time to write: I think being single helps, though a romance would be nice, even a spotty one. I don’t like to write. I wait and wait until my body is fed up with me. That is why I write nights into early mornings—the lonely hours. It makes for a tiring daytime, but driving out the words feels wonderful.

Putting the book together: I initially had the collection separated into four sections, in the order I’d written them in. First came “Crown for Peasant Heads,” then “Three-Part Inventions”—named after Richard Howard’s Two-Part Inventions (Antheneum, 1974)—“Profanities,” and the section I hated, “Neither Divine or the Garden Like It,” which became the ossia. In the editing process my editor Kyle Dacuyan asked me if I would consider reshaping the book, to have the voices collide and speak to each other. I spread out each poem on the floor and shaped the book again. I followed the logic of how I would program a piano recital, a theme with variations where each ghost reappears and disappears. The crown of sonnets was moved to the end with a translator’s preface written to close the book da capo (begin again).

What’s next: I’ve finished a chapbook titled A – 1982 (out winter 2024–2025) for my friend Ian U Lockaby, who curates the incredible online zine mercury firs. I’m spinning the chapbook into a full-length collection. I want to find out why I am so averse to writing about myself; I’m fond of saying I have no interest in my own personal narrative. It traverses my queerness, my family’s gas station, the disaster of petrol as the lifeblood of my immigrant family’s livelihood, and asks: What is autobiography beyond narrative detail?

Age: 42.

Residence: I recently moved back to Brooklyn, New York.

Job: I work as a personal trainer, tutor, and adjunct.

Time spent writing the book: I began in September 2020 and finished a complete draft by October 2022.

Time spent finding a home for it: I submitted my manuscript to contests beginning in April 2021. I was a finalist for the 2022 Nightboat Poetry Prize (rejection) and received encouragement from Action Books (rejection). I submitted to the National Poetry Series (rejection), Wesleyan University Press (rejection), Four Way Books (rejection), Futurepoem (rejection), the APR/Honickman First Book Prize (rejection), and Tin House (rejection). Changes Press accepted my collection in January 2023. I’m grateful for the previous rejections, though, because I saw them as a way to continue asking my questions. Questions I hope I never fully answer so I can examine whatever it is I see from all possible vantage points—if I even know what those questions are, that is. Richard Howard used to say, “You must work on the next great thing.” If our questions are always new, so are our answers. And I can keep writing.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: Megan Pinto’s Saints of Little Faith from Four Way Books is a beautiful and exacting account of familial, romantic, and platonic love—something I wish I could do. Azad Ashim Sharma’s fourth book, Boiled Owls from Nightboat Books, masterfully moves through, and beyond, addiction within our socio-political wreck and reckonings—Sharma really is a Late Modernist. Jay Gao’s recent poetry pamphlet, Bark, Archive, Splinter from Out-Spoken Press, looks at man-made history through the cyclical eternity of trees—nature as the witness to human folly; it makes me honor the sentinel, and the sentient stewardship of trees. Ian U Lockaby’s Defensible Space/if a crow— from Omnidawn Publishing takes our familiar domestic and natural tangibles and refracts them through the bird’s-eye view of the wonderous, ill-maligned crow. The distance of Lockaby’s tactical if, as if to show how the distance between our sight and worldly objects is only truly visible by breaks in poetic syntax. And finally, Asa Drake’s Beauty Talk forthcoming from Noemi Press in 2026. I love the way Drake’s poems reveal every bit of our psyches; her ability to do this reminds me of George Eliot’s omnipresent narrators.

OSSIA by Jimin Seo.