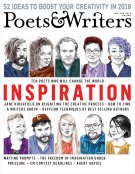

For the past eight years we have commissioned original artwork for the cover of our annual Inspiration Issue, resulting in incredible designs by Chip Kidd, Jim Tierney, Polly Becker, Roman Muradov, and others. For the January/February 2018 issue, I reached out to author and illustrator Edward Carey, whose beautiful illustrations for his own novels, including Observatory Mansions (Crown, 2001) and the Iremonger Trilogy, beginning with Heap House (Overlook Press, 2015), possess a unique, dark quality that I thought might acccurately reflect the reality of the world that writers are navigating right now. The idea was to produce a sculpture that acknowledges the darkness while offering a message of hope: that writers, when inspired, can cut through the noise and the fear and the anxiety, and create something beautiful, meaningful. In short: Writers can change the world.

The sculpture commissioned for the cover of the January/February 2018 issue. (Credit: Edward Carey; photo by Nick Cabrera)

The sculpture that Carey created does exactly that, but none of us were expecting the power of his imagery to evoke the feelings of fear and anxiety we wanted to acknowledge on our cover. The darkness, it turned out, was darker than we had thought. After much discussion and back and forth, we decided to go in a different direction. Still, the sculpture was so haunting, so inspiring, that I wanted to talk with the artist a bit more about his thinking behind the work. Disappointed, yet understanding of the pressures to strike just the right notes on a magazine cover, Carey agreed to an interview. His thoughts on his own work as well as the work of writers everywhere during these trying times are—like the light that shines on his sculpture—illuminating.

First of all, I love your visual work. When I first encountered your illustrations—those in Heap House are so arresting—I was drawn to what I see as a fairly dark sensibility, for lack of a better term. I only recently came across your work in clay, which to my eye shares some of those same dark turns. How would you describe your work?

I think probably my work could be summed up as dark fairy tales. When I draw I might try to draw someone young and beautiful and happy but the result would always turn rather melancholy or grotesque. I grew up being given Charles Dickens as a sort of medicine in school—everyone had to take it—and I loved it. I could never get enough of Miss Havisham or Quilp or Uriah Heep or Sairey Gamp. When I was eight or nine some of William Hogarth’s etchings were in a history textbook; I could never forget them. Gin Lane, in which a great many people are dying from alcohol abuse and a young child is falling from his drunk mother’s lap to his death, haunted and fascinated me. I was always drawing, and the people I drew were always slightly miserable and rather dark.

Dark fairy tales, yes! That really captures the feeling I get when I see your work—and that includes your sculptures; for example, the beautiful (and complicated) figure you created for our cover. When I first approached you with an invitation to cover our Inspiration Issue, it was a rather open-ended suggestion: something inspiring that acknowledged the struggles that we, as writers and citizens of this world, have experienced during the last year. Can you describe your thinking behind the figure you created?

I wanted to make a face one half deeply anxious, deeply unhappy at what is going on about us, but the other half, which has the ear protruding out a little, still existing still thinking, still being positive, still being inspired despite the daily horrors—fighting, I hope, certainly not giving up. No matter what you write it’s hard, it’s impossible, not to be considering the sudden and horrific missteps that are being made about us—the hatred, the cruelty, the bigotry—but that can’t stop us from writing. More than ever I hope it makes us write with great determination. So the bust for the cover is a sort of phrenology head gone awry, read from left to right—and on the right side there’s meant to be a certain, unquenchable hope.

Unquenchable hope is exactly the kind of message we hope to send to readers of the Inspiration Issue! And yet by now you and I have talked about how we needed to take the cover in a different direction. I think we underestimated the power of acknowledging, in visual form, on a cover, the darker aspects of what’s going on around us. And I think our difficulty with it really speaks to the strength and urgency of your work. Returning to this idea of unquenchable hope: Can you talk a bit about what gives you hope? To what do you turn when you need a fresh, perhaps brighter, perspective on things?

If I’m not writing or drawing I’m miserable. The moment I’m really lost in a project the happier I feel. I love the quote by Saul Bellow: “Perhaps being lost one should get loster.” It’s the act of working that gives hope I think. Right now I’m writing a novella and making some artwork for an exhibition and publication next year in Italy. I was given a commission to make an exhibition for the Parco di Pinocchio in Tuscany, I’ve always loved the Collodi book [The Adventures of Pinocchio]. As I began to reread the book and to draw, I became fascinated again by Geppetto, Pinocchio’s father. He is poor and aging, but he never stops creating. In his home he is very cold, so he paints a trompe l’oeil fire on his wall. He is lonely and so makes his own son and that son, of course, comes to life. In Collodi’s book, Geppetto is swallowed by a monstrous shark and spends two years inside the shark’s belly before being rescued by Pinocchio. In the book these two years are merely mentioned in passing, but I began to wonder what art Geppetto would create inside such a hideous prison. So I’ve set about making that art. And it’s the creation of that art, the business of it that keeps him alive.

I think, perhaps we’re all inside a shark’s belly at the moment, and defiantly working is what keeps us going. Things will get better. I hope. Surely.

Kevin Larimer is the editor in chief of Poets & Writers, Inc.