The Lucky Ones

Zara Chowdhary

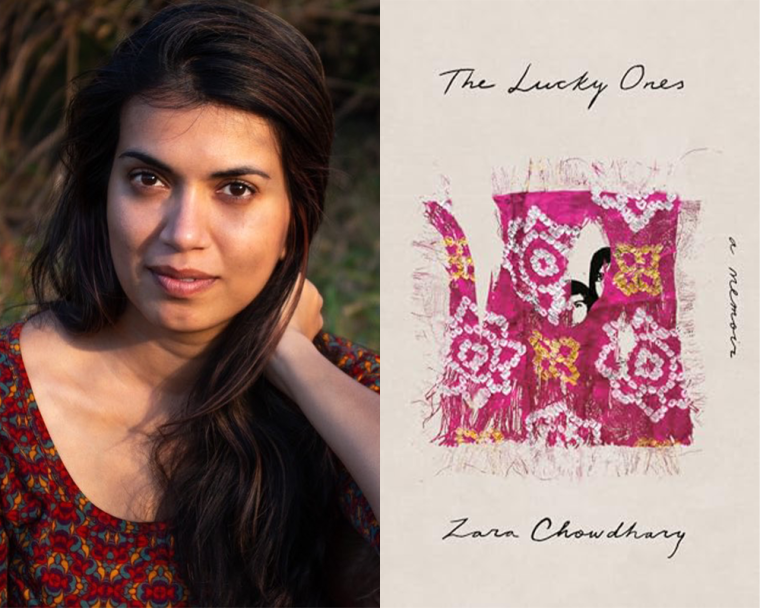

Zara Chowdhary, whose memoir, The Lucky Ones, was published by Crown in July. (Credit: Caitlin M. Carlson)

Indefinite Postponement

Our board exams should have taken place on March 11. But two weeks after the train burning, on March 16, it’s officially announced: The Education Board has indefinitely postponed board exams for the whole state. We watch the words come out of the local Gujarati news presenter’s mouth, same as we watch news of death and blood.

I don’t feel a great sadness. If anything, there is a modest certainty. I feel convinced these exams, which were made into life-changing, career-making finalities, are a joke. Young teenagers in India end their lives over a bad board exam result. Now ending Muslim lives has taken precedence over them.

My mind wanders to the invisible bodies lying just beyond the reach of my fingers, across curfewed windows, through the fog of the city’s lockdown. We’re living in a tower from which nothing is visible, not the mob, not the dead, not the surviving, not my school friends. There is only this idiot box, and the idiots—the BJP, VHP, and Bajrang Dal—in it, given free rein to spew hate at us, their captive audience all day.

The city police commissioner’s face appears on the screen. Four people stabbed in Ahmedabad yesterday. This morning in another clash one person shot and killed in police firing. I don’t need exams. I’m learning right here, feet glued to this tile on Dadi’s mosaic floor, how passive voice changes everything, how words cover unspeakable things. How a clash is really a Hindutva mob running over yet another Muslim home/business/neighborhood, cowering, terrified innocent people. How stabbing means tridents, those holiest of weapons, smeared in human blood. How killed in police firing means shot when they resisted their slaughter. I’m learning that as I stand here safe in Jasmine, tenth graders in refugee camps a few blocks away have forgotten what homes and schools look like. I don’t give a fuck about the boards. I haven’t learned to effectively use the word “fuck” yet. But I’m learning there are words in which this seething fever I feel must pack a punch. I need to punch something.

Apa seems oddly quiet about the whole boards-postponement news, even though it’s all she has pestered me about since she and her mom moved back in with us. What if they cancel it? All of you will get a free pass? Even the dummies! I guess we’ll never know how you could have scored.

She’s only a year older, and this same time last year, in 2001, she was taking her boards. She’d spent all her tenth grade in stress-induced fevers and loosies because being a stress bucket had become her entire personality. She’d given herself mock test after mock test, crammed piles of textbooks, solved every possible math problem in every practice workbook she found. Then in January, a deadly 7.9 earthquake had struck just weeks before her boards. Thousands dead and displaced across the state. We had left Jasmine and moved in with our Hindu family friends, the Shahs, in their modest bungalow. All students statewide had gotten a free pass from school under the previous chief minister, whom Modi would soon replace. Except tenth graders. The boards were held despite the dead. Apa, quaking from the sleepless, displaced nights, had taken her exams and gotten straight A-pluses. Our jeweler cousins in Mumbai had gifted her a diamond-and-pearl necklace for her bravery and brilliance.

When Phupu moved into Jasmine Apartments after her marriage ended, she had Apa, a tiny baby girl of six months, in her arms. In a home that didn’t know how to deal with failure, especially involving a daughter, Apa was both a constant reminder of it and a reproach to the men, urging them to overcompensate for the man missing in her life. Dada was always fiercely protective of her. Especially when Dadi venomously attacked the child for bringing “bad luck.” Manhoos, she called her. Sometimes Dada needed to protect her so much that if Apa got into trouble, he would come looking for me to scold me and equalize the scoreboard. Papa was also similarly programmed to temper his affections toward his daughters so Apa wouldn’t feel left out. He took the shortcut and ignored all three girls equally.

When we were very young, Amma would sit Misba on one side of her lap, Apa on the other, and me across, and take turns mashing rice and dal into tiny, perfect, bite-size niwalas to feed us each from the same plate. She would eat last and least at the emptied table. When I turned three, she sat me at the dining table with a plate in front of me and whispered, “You can do this. Those two still need me. I know you can do this.”

I remember staring at the plate—dal and chawal and sabzi all swimming across the steel, melding into one another in a way I hated. I remember the exhaustion in her voice. I remember struggling to make a niwala of rice and dal, the sloppy mess slipping down my fingers, sliding down my elbow, dripping onto my dress. I remember shame at being too old to be learning how to feed myself. I remember going to the kitchen, reaching over the large sink, washing my hands, and grabbing a spoon. I would never learn to use my bare hands to eat.

As she watches me now, digesting the news of the postponement, Apa simply curls her lower lip and makes a “mtch” sound. Mild condolences. I know what she’s thinking. Genocide totally trumps an earthquake. But our home has been quaking for years. If I don’t take the boards, it will be yet another thing added to my list of underachievements. Meet Zara. Slim, tall, convent educated, sure. Soft-spoken, mild-mannered, yes. But probably not very smart. We can’t say. She didn’t take her boards.

Excerpted from The Lucky Ones: A Memoir by Zara Chowdhary. Copyright © 2024 by Zara Chowdhary. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.