In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 184.

I am admittedly a cold-blooded creature, which is to say I run chilly naturally and am therefore always following the sun, wherever its rays land. I am grateful when I sit next to someone on the subway, especially during the piercing frigidity of winter, and a bit of their warmth transfers to my person. I need that fire to keep me going. It should therefore come as no surprise that when writing my debut poetry collection, fox woman get out!, published by BOA Editions in September, I sought to create a very large fire to warm both me and my readers, as I see that as an act of survival and, beyond that, care.

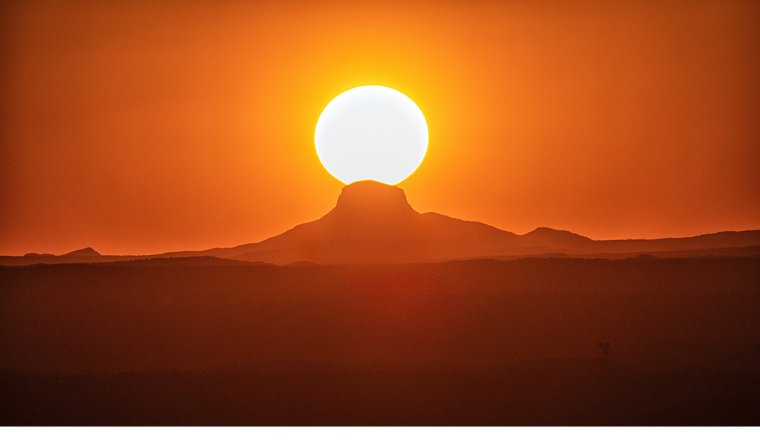

This idea of temperature in writing came back to me recently when I was giving a poetry reading hosted by one of my undergraduate professors. He said that when he first encountered my work he thought I came from a desert landscape, somewhere like Texas, because he found the climate of my poems to be dry and hot. I’m from Washington, D.C., originally, but my former professor aptly sensed the innate blaze within my work. He then asked me and the other readers at the event: What is your psychic climate? I offer this question to you now, dear reader, to help ground you even more in your creative practice. For paying attention to temperature and climate within our work puts us in touch with the natural world around us and within us.

Marguerite Duras is a writer I would characterize as having a frosty psychic climate. In high school I first encountered Duras’s The Lover (Pantheon, 1998) and was astonished by the cold precision of the book’s language. The adolescent French girl at the center of the novel was unusually tough and in control of her lover in a way I had never before read regarding a young, female character. “One day, I was already old,” the book opens. Reading those words, I knew I would be ravaged by this melancholic, young girl who rushes into adulthood. Duras’s language is terse at times. Abrupt and short, rhythmic sequences revealing the protagonist’s thoughts—in both first-person and third-person narration—keep the reader at bay, yet make them just curious enough to continue. “The story of my life doesn’t exist,” the narrator says near the beginning of the novel. “He says he’s lonely, horribly lonely because of this love he feels for her. She says she’s lonely too. She doesn’t say why,” writes Duras right before the narrator’s first intimate encounter with her beloved. Duras teeters between giving the narrator a certain aplomb and mysterious air, while also allowing the reader in on remarkably intimate moments, the desire of her younger self, which adds a necessary fire throughout.

Later, in college, my sister recommended that I read Richard Siken’s debut poetry collection, Crush (Yale University Press, 2005). The electricity of each line moved through me on a physical level; the book was a necessary gut punch. In her foreword to the book, Louise Glück even remarked on her physical, temperature-based response to the collection, citing Emily Dickinson’s words as a point of reference: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that it is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that it is poetry.”

In Siken’s poem “Dirty Valentine,” which narrates the speaker’s fantasy of a film starring him and his deceased lover, Siken uses serpentine stanzas to add to the emotional urgency of the speaker’s longing, this ruptured performance of love. The zigzagging lines create a path for us to keep moving along or get sucked into, like some sort of winding tornado; as we read, we hope that the deep sentiment behind this dizzying film performance will lead the couple to a more innocent and present love. Every thought is a quick rush of heat, too high-voltage to be grouped in longer lines, adding to the emotionality of the language, which is amplified by the surrounding scenery:

There’s a part in the movie

where you can see right through the acting,

where you can tell I’m about to burst into tears,

right before I burst into tears,

and flee to the slimy moonlit riverbed

canopied with devastated clouds.

Then there are moments of tenderness within the collection, a body of water to allow for sorrow, the feeling of drowning in one’s longing. In the poem “Saying Your Names,” Siken, in left-aligned verse, offers the reader and the speaker a moment of rest, allowing the movement of his language to settle down and his tone to become remarkably soft:

... Please keep him safe.

Let him lay his head on my chest and we will be

like sailors, swimming in the sound of it, dashed

to pieces.

The temperatures of those two books have not left my body to this day.

Let’s now turn this topic inward, exploring our own writerly temperatures: Does your poetic degree of hotness or coldness match the natural temperature of your body, of where you were born, of where you currently live, of where you hope to live? Look at the length of your stanzas, where you choose to break lines, the musicality of your language (your pacing, use of rhyme, consonance, and assonance), how you utilize form on the page, how distant or present you are emotionally, how much the “camerawork” of your poems zooms in on the speaker and what they are witnessing, how you might turn the camera away before revealing too much, where you choose to locate your poems in space (outside or inside), and what the climate of that location allows for. See what temperature you may be transferring to your readers.

A more embodied, and less literary, way of understanding our poetic temperature involves taking time to be more actively present in our bodies throughout the days, seasons, and years. Take note of whether you prefer a blanket on top of you to fall asleep, need the air conditioner on at night or a window open in your room to feel the outside air. If you’re walking, hiking, or working out, how soon do you begin sweating? Do you sweat at all? How fast or slow is your heart rate throughout the day? What’s your natural talking pace? All these details can manifest as a certain temperature in our poetry, and the more aware we are of our answers to these questions the more aware we can become of ourselves—and the more present and knowledgeable we can become when showing up to the page.

There are myriad ways to think about and write into one’s poetic temperature, including how you go about building a certain climate or mood before turning the thermostat of your poetry down or up to maintain a sense of balance throughout. However cold-blooded or hot-blooded you may be (let’s not forget that temperature and temperament are linguistic relatives), use your innate and literary temperatures to move your readers, so that they too will carry your words in their minds and bodies for years to come.

India Lena González is the features editor of Poets & Writers Magazine, a poet, and a multidisciplinary artist. Her debut poetry collection, fox woman get out!, was released this fall as part of BOA Editions’ Blessing the Boats Selections. India is also a professionally trained dancer, choreographer, and actor and has had the pleasure of performing at Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, St. Mark’s Church, La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, New York Live Arts, and other such venues.

Art: John Fowler