Nunez credits Elizabeth Hardwick, her undergraduate professor at Barnard College, for her interest in the hybrid genre. Although influenced more by her writing than her teaching, Nunez says that Hardwick, the author of the essay collection Seduction and Betrayal (Random House, 1974) and the novel Sleepless Nights (Random House, 1979), made an indelible impression. “So there she was, the first writing teacher I ever had, the first writer I ever met. But ultimately I was so drawn to her prose—it’s exquisite.” Nunez found herself imitating Hardwick, who is known for her witty and sophisticated essays, as well as for autobiographical fiction, but, Nunez says, “that’s when I was young, and, of course, it came out badly.”

After graduating with a degree in English from Barnard, in 1972, Nunez worked as an editorial assistant for the New York Review of Books before enrolling in the MFA program at Columbia University. She admits that she never found the creative writing workshops there to be “particularly inspiring.” Now a teacher herself, she says she begins each workshop by telling her students that “they will learn far more from reading other writers than they ever could in a writing class.”

In The Last of Her Kind, Nunez writes a scathing indictment of the traditional workshop scenario in her description of Georgette’s poetry workshop at Barnard. The teacher tells students to omit their names from their work so they can talk more honestly about them, “without personalities getting in the way.” Georgette knows, however, that “she might as well have said, So that you can be as tactless and brutal as you wish.” The class star’s “dragon hiss of contempt” is deadly to Georgette, and it kills more than her desire to write poetry: “That class helped set things in motion, coloring my attitude toward all my other classes, toward being in college in general, intensifying my fear of not belonging, of not speaking the same language as everyone else—a language I might be capable of learning enough to get by, but in which I would never be fluent.” As in much of Nunez’s fiction, the scene contains a kernel of truth. “I don’t think it’s that uncommon,” Nunez says. “I did indeed have an experience like that. I remember it very well, and now the things I didn’t like in workshop are what I as a teacher won’t do.”

After receiving her MFA from Columbia, in 1975, Nunez returned to the New York Review of Books, where she met another influence on her work, the late Susan Sontag, who was at that time a regular contributor to the magazine and was recovering from her first bout with cancer. “She was getting herself back on her feet after surgery and had this big pile of correspondence,” Nunez explains. “She asked that the Review get someone to help with the typing. I lived on 106th Street, near her apartment on Riverside Drive, so I started going over to help her. That’s when I meet David Rieff, her son, and we ended up together. The three of us lived in the same apartment in the late 1970s. After David and I broke up, I saw Susan only occasionally.”

Sontag introduced Nunez to the work of writers and artists, especially those from Europe, such as poet Rainer Maria Rilke and novelist Milan Kundera, whose work, she says, “helped shape my intellectual development. Sontag’s attitude of high seriousness toward literature and her exalted view of the writer’s vocation struck deep chords in me.” Nunez cites Sontag’s story “Project for a Trip to China,” an example of the hybrid genre, as being particularly influential on her early work.

![]()

After A Feather on the Breath of God, Nunez decided to write a traditional novel, one that drew more from the author’s imagination than from her autobiography. Naked Sleeper (HarperCollins, 1996), which centers on Nona, a writer and teacher whose marriage is in crisis, garnered generally positive reviews, but it did not receive the high praise of her first book. She followed that up with a third novel, Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury (HarperFlamingo, 1998), a “mock biography” of Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s pet marmoset. Nunez calls it a “jeu d’esprit,” and says the book was inspired by Flush, Virginia Woolf’s biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel. More whimsical than her earlier works, Mitz is, by Nunez’s own description, “in the hybrid genre because it contained more nonfiction than fiction. I wanted to tell the story of their lives during that period [the autumn of the Bloomsbury era]. They really had this monkey, and I used authentic Bloomsbury documents—Virginia Woolf’s letters and diaries, biographies, her husband’s autobiography—in order to create what is a completely historically accurate document of those times. But, of course, it’s about a monkey, so I had to invent a certain amount to make the story interesting.”

For Rouenna, Nunez’s next novel, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2001, was seen by many as her breakthrough work, garnering enthusiastic reviews. One, in the Women’s Review of Books, written by Suzanne Ruta, called the book the product of “a gifted author finding her subject, her mission and her full voice, all in the same place.” In the book, Nunez explores the character of Rouenna Zycinski, a former U.S. Army nurse who served in Vietnam. She is a composite, Nunez says, of various people she’s known. Rouenna writes a letter to an author—the book’s narrator—after she reads her novel and realizes that the two of them grew up in the same housing project. Alternately drawn to and repelled by this woman, now middle-aged and grossly overweight, the author-narrator decides, after Rouenna commits suicide, to tell her story. What follows is a kind of metafiction that is as much about the author-narrator as about Rouenna.

But then, most of Nunez’s writing seems to be about the narrator—or the writer. Her rich fictional lives often more closely resemble Nunez’s own life than is apparent during the first read. Even the narrator of Mitz, set in the 1930s, refers to contemporary events and figures, such as the 1995 film Carrington and critic Harold Bloom, and reviewers have noted Mitz’s “shared characteristics” with Nunez herself. Among the “dazzling possibilities” that the hybrid genre affords her, Nunez says, is the narrative opportunity to invest more of herself and her history into her characters’ lives. With each succeeding book, Nunez discloses more of herself, and at the same time she obscures, or just plain ignores, the line between fact and fiction.

In the new novel, Nunez revisits the setting—the turbulent years of the ’60s—of her previous book, For Rouenna. “But this time I was interested in taking people from completely different backgrounds and putting them together during a critical period in their lives— the college years,” Nunez says. “I liked taking something that was autobiographical, revisiting a time and place that I actually lived, so even though the story itself did not happen [to me], the atmosphere was completely familiar.”

The vividness of the writing in The Last of Her Kind seems to mimic deft camera moves and angles, to show the interior of an elegant restaurant, where Ann meets her parents and treats their every word with the same contempt she has for every morsel of fancy food, or the exterior of Riverside Park—the setting that Georgette has chosen for the private joy of being able to sing unheard but which later becomes the site of a violent crime.

What will also be familiar to Nunez’s readers in The Last of Her Kind is her slightly detached authorial stance. There’s a simultaneous engagement and distancing from her characters’ intense emotional and political lives—a style that Nunez has employed since A Feather on the Breath of God was published, more than ten years ago. In that novel, the narrator remarks on “the miraculous possibility that art holds out to us: to be a part of the world and to be removed from the world at the same time.”

“I think this is what Goethe meant,” Nunez says, “when he said that art is something you do by yourself, but when you’re finished, you share it with the world and participate with a larger community. The practice of art is extremely private, yet it brings you into the world.”

Whether she is telling her own story or the story of one of her fictional characters—or something tantalizingly in between—Nunez is a gifted storyteller. She says she’s currently working on a series of “autobiographical essays” that may or may not become a book. Whether one of her works is called an “autobiographical novel,” a “fictional biography,” or just a good, old-fashioned novel, her readers know Sigrid Nunez through the secrets and lies of fact and fiction, even if they can’t always tell the difference between them.

Renée H. Shea, professor of English and modern languages at Bowie State University, has written profiles of Andrea Levy, Rita Dove, and Sandra Cisneros, among others, for Poets &Writers Magazine. She coauthored Amy Tan in the Classroom: The Art of Invisible Strength, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, in 2004.

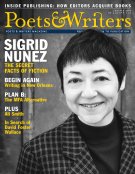

(Photos: Pieter Van Hattem)