Morally indefensible—that’s what Janet Malcolm calls the work of the journalist in her seminal book The Journalist and the Murderer (Knopf, 1990). “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness.” Malcolm’s point is that the journalist-subject dynamic weighs heavily in favor of the journalist, who has the power to interpret the subject’s story. Bottoms quotes the passage in The Colorful Apocalypse to demonstrate the difficulty of writing about another person’s life.

To write about Finster, Thompson, and Kox, Bottoms traveled to Georgia, South Carolina, and Wisconsin, to unfamiliar places to talk with unfamiliar people—artists who have painted images of the Virgin Mary as a skeleton with the severed head of Jesus Christ on her chest, for example, or who have built sculptures of dead babies and whose views on religion, spirituality, sexuality, abortion, and other issues Bottoms struggled to understand. (On his Web site, artist William Thomas Thompson offers a statement of his beliefs. “I believe that the so-called mother church is a false religion,” he writes. “I believe the dynasty of Popes to be the Antichrist. I believe that America is the real promise Land and breadbasket for the entire world. I believe Revelation prophecy is largely fulfilled already.” Kox, too, introduces himself on his Web site, stating that his artwork illustrates how “much of modern Christianity has been duped by the Adversary and has actually become the religion of the Antichrist.”)

“I didn’t go down there thinking, ‘Gee, my own confusion is going to be a part of this story,’” Bottoms says. “But once I started to talk to these people I felt this need to not present something that felt like thesis or synthesis so much as encounter—an openness to encounter itself—and also a willingness to see other people’s perspectives and not just stand in easy judgment.”

To accomplish this, Bottoms included himself in the narrative, together with all of his misgivings, misunderstandings, and missteps along the way. (The book is classified as a travel memoir.) He also made very clear to his subjects that he was a journalist writing a story. “I feel like I was pretty up front and honest all the time with these people and actually took care with the way I was writing about them,” he says.

Bottoms reveled in the philosophical implications of narrative and embraced “this idea of life-writing, of biography and autobiography and memoir, of telling other people’s stories and telling your story and making their story a part of your story,” he says. So, armed with a tape recorder and notebook, Bottoms talked to the artists about their work. But mostly he listened.

He wasn’t Truman Capote in Holcomb, Kansas, befriending—and, some say, taking advantage of—murder suspects whose execution formed the perfect ending to his “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood. Nor was he James Agee, whose paralyzing guilt while living with sharecroppers in Alabama influenced every word of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. But Bottoms did take his role seriously and tried to offer his readers a documentary of sorts. “To me, these artists’ stories were complicated human stories,” he says. “I don’t think of any of these people, anybody in this book, as aberrant or strange, but there is a way you can look at them and say they are obviously this or obviously that.”

Bottoms had run into those kinds of assumptions before, back in Hampton, Virginia, and wanted to avoid them. “The way in which my brother’s story was told in newspapers and neighborhood gossip and became a kind of suburban tale told among kids—it was wrong, it was too simplified,” Bottoms says. “And I’m suggesting it’s the same here with these people’s lives.”

While his role as a writer—one who would look and listen and ask questions about the artists’ intentions, take what he encountered, and add it to his own views and experiences—was clear to him, Bottoms was concerned that his intentions were not so clear to his subjects. “I think they, in some ways, perceived me as a vehicle to disseminate their message, so I wanted to keep being honest with them about who I was,” he says. “I think they assumed I would reel off something promotional.”

The publication of The Colorful Apocalypse was met first with reviews—Sven Birkerts called it “an intensely searching tribute”—and then a flurry of impassioned e-mails and letters from Kox and Thompson (who have collaborated on a number of paintings, including “Idolatry: The Drugging of the Nations,” which is reproduced on the cover of Bottoms’s book) denouncing it as “a compilation of lies and half-truths.” Posted on Publishers-weekly, Amazon, Powells, and other Web sites and blogs were customer reviews, comments, and even letters from the artists to the University of Chicago Press demanding a recall of the book. Bottoms’s descriptions of paintings were called into question, as were paraphrased statements and direct quotes, which Bottoms says he has recorded conversations and notes to support.

“Greg Bottoms has twisted the truth and fabricated much of the information in the book,” Kox stated in a message on Publishers Weekly’s online Talkback feature. “His colorful inventions are in many cases total falsehood. The Colorful Apocalypse is a blatant example of inaccurate and deceitful writing.”

In his reply to the artists, which was posted on Powells and later removed, Perry Cartwright, the manager of contracts and subsidiary rights for the University of Chicago Press, stated that the press would be happy to correct specific factual errors in the book if it was reprinted. (Bottoms has admitted to one erroneous description—of the numerical significance of a detail in a Kox-Thompson collaboration. “That’s the full fruit of their complaints,” Bottoms says.) “From your letters it seems that there is a significant misunderstanding about the essence of this book,” Cartwright added. “A book of this type is by its very nature subjective, so it is entirely possible, and not deceptive, that his views of what he saw will not always be in total agreement with the views and opinions of you or other artists and observers.”

The author himself took it a little more personally. “Being called a liar really bugs the heck out of me,” he wrote in his reply to Kox’s review of the book on Amazon. “Only the most frighteningly zealous among us believe they own ‘the truth.’ I don’t believe I do, and this book about my experiences, understandings, confusions, arguments, and insights is in no way meant to supplant the artists’ own narratives of who they are, what they believe, and what they represent.”

Executive editor Susan Bielstein says the University of Chicago Press has no plans to recall the book. “We prize our relationship with Greg Bottoms.”

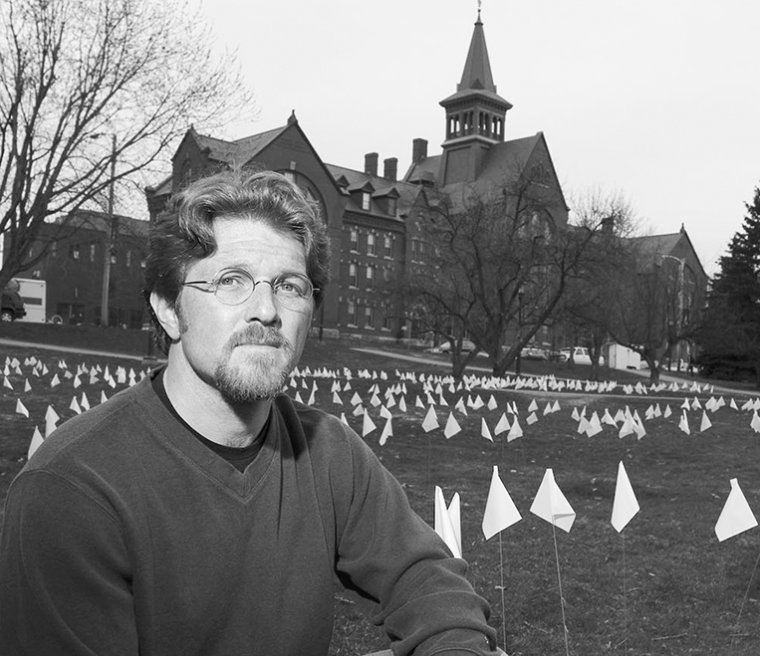

![]()

Burlington, Vermont, is a long way from Hampton, Virginia. Light-years away, says Bottoms, who since 2003 has taught literary nonfiction at the university there, which sits on a hill at the foot of the Green Mountains. It’s also a long way from his family and from the outsider artists he came to know during the past six years. Although New York City—with its agents and editors and publicists and reviewers and best-seller lists—is only three hundred miles south, one gets the sense that Bottoms is not a frequent visitor. Nor does he worry much about the business side of publishing it represents.

“Commercial expectations seem separate from my own impulse to write,” he says. “I feel like my books are kind of willfully literary—not fancy, I try to be totally accessible—but a book about outsider artists? A book about a schizophrenic kid? A book of essays about a suicidal writer and a janitor who made a gigantic sculpture? It seems strange to me sometimes that anybody reads them at all. I’ll write another book after this one, I’ll write another book after that one, and I daresay probably none of them will be commercially successful. I can’t imagine that they would be. And that’s okay with me.”

Still, the controversy surrounding his latest book has taken its toll. “This has been terribly deflating to me,” Bottoms says. “I’ve felt pretty shitty since the thing came out.” But if, as the author’s own story illustrates, every nonfiction writer is, in the eyes of someone somewhere, a liar, then Bottoms is the best kind of liar. He’s a writer who avoids the “automatic and easy assemblage of the facts” by digging below the surface of the story, who keeps writing until he’s staring straight into the face of the only truth that is truly indisputable: his own. Kevin Larimer is the editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.