Michele Filgate is the writing world’s equivalent of a community organizer. She’s the founder of Red Ink, a quarterly reading series at Books Are Magic in Brooklyn, New York, that focuses on women writers; a contributing editor at Literary Hub; and a former board member of the National Book Critics Circle. She also teaches creative nonfiction for the Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop, Catapult, and Stanford Continuing Studies. In all of her work, Filgate goes out of her way to promote fellow writers and ensure that their writing finds, well, a warm community.

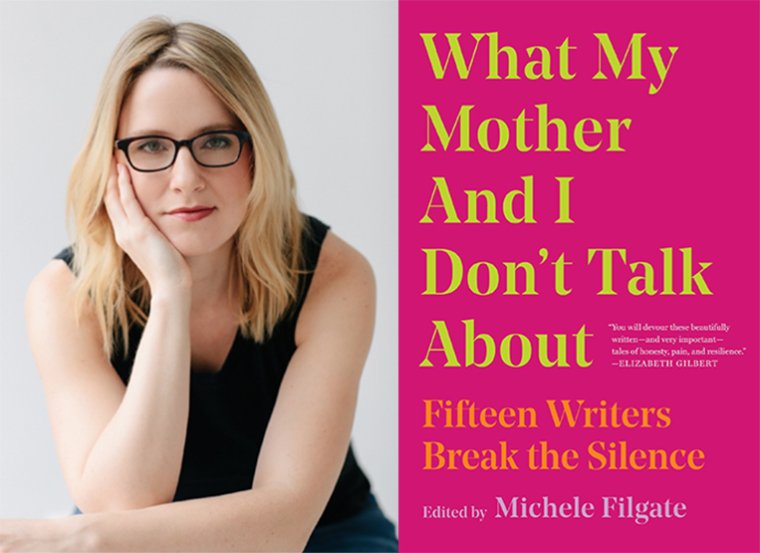

So it’s no surprise that her first book is an anthology. What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About: Fifteen Writers Break the Silence, published by Simon & Schuster on April 30, is full of tender and fierce and sad and hard and intimate and sometimes funny stories about mothers. Contributors include Melissa Febos, Alexander Chee, Dylan Landis, Kiese Laymon, Carmen Maria Machado, André Aciman, and Leslie Jamison. The book grew out of an essay Filgate wrote about her increasingly fractured relationship with her mom after she refused to acknowledge the abuse Filgate had endured at her stepfather’s hand. Longreads published it just as the news of Harvey Weinstein broke; it quickly went viral.

I spoke with Filgate about the mother wound, the importance of writing our bodies, and editing some of her favorite writers.

“Our mothers are our first homes, and that’s why we’re always trying to return to them.” This is the opening line of your essay and one of the most beautiful sentences I’ve ever read. Are you still trying to return to your mom?

Absolutely. At its heart, this essay is about longing. I want it to be possible in real life that my mother and I can reconnect, and I hope that this essay will help our relationship in the long run. Right now, things are complicated and painful. And I put that pain and heartbreak into this essay. I don’t think it’s written from a place of anger or resentment, at all. It’s written from a place of desire to have a relationship where we can communicate. We haven’t been able to really communicate in a long time.

What would it look like if you could return?

My dream would be that we could have a conversation where both of us are listening to one another, and where my mother is not denying the truth.

I hope that happens. It took you over a decade to write your essay. Why?

For a long time, I was blinded by wanting to write about “look at what my stepfather did to me.” It took many years of therapy and writing to realize the story was much deeper than just my stepfather. The real story is the fracture that this caused in the relationship with my mom and that’s where the deepest source of pain is in my life. And that meant I had to reenter, reimagine these scenes. I had to go to a place I’d tried to avoid for so long. So, part of it was needing years of experience as a writer, knowing my own voice. And part of it was many years of therapy.

You write that what you learned from Jo Ann Beard’s essay collection The Boys of My Youth was that a personal essay can be “a place where a writer can lay claim to control over their story.” Have you found that this “claim to control” spills from the page into your daily life—or does the story keep evolving?

That’s an excellent question. That story keeps evolving. I think it’s much easier to feel in control on the page than it is in real life. In real life things feel like they’re impossible to control, right? One of the reasons I’m a writer is because I like being able to figure out the narrative I’m telling and why it’s important I’m telling it. I’m constantly trying to figure out why it is I need to say what I want to say and why is it I want to write what I want to write. And I often I need to write to figure out how to live, if that makes sense.

You included fourteen wildly gifted and diverse authors in this anthology. What drew you to these writers?

To me the job of an anthology editor is first and foremost to make sure you’re getting a variety of different stories, so I wanted to reflect a diversity not just in the writers themselves but in the types of relationships between mother and child. I didn’t want it to be all mothers and daughters. And I didn’t want it to be all abuse stories, or really devastating, depressing essays—although there are some of those. It was important to have some writers who are close with their mothers. The core of why this anthology exists is that everyone no matter close they are with their mother has something they wish they could talk to them about. Even and especially if they never knew their mother, or if their mother is no longer alive.

What was like to edit Kiese Laymon and Leslie Jamison?

At first I thought it would be intimidating, but it really wasn’t because at the end of the day we’re all writers and I think that writers, no matter what stage they’re in in their career, are usually very respectful of the editorial process. When you have an editor who sees your work in a certain way and is able to help you shape it then that’s a gift. I took that approach. It was a very special experience. But this was a team effort: I also had the help of my extraordinary editor, Karyn Marcus.

Did playing the role of editor impact your own writing?

Absolutely. The thing about editing an anthology is it’s a reminder of how much work it can be to get to the right place with a particular piece of writing. Most of us don’t just churn out a great piece in one draft; it’s often several drafts. So, it reminded me that writing is very much about revisions.

In her essay, Melissa Febos describes her mom’s reaction to Melissa’s memoir that depicted some hard things in Melissa’s life that her mom was unaware of. Melissa writes: “I’ve had my own experience of it, she [her mom] once said. I knew she meant that she wanted me to make room for how it had been hard for her, too.” I know your mom is not pleased about your book. Do writers have a responsibility to the people we write about?

That’s a question that’s always on my mind. I know a lot of writers who won’t publish anything about a loved one while they’re still alive or without getting permission from them first. But what if you can’t ask for permission because you’re afraid you’ll be silenced? I think the responsibility we have to others that we’re writing about is to write the truth. Sometimes that really hurts. But unpleasant truths are part of what it means to be a human—and breaking the silences around shameful or difficult stories is part of our job as writers.

You write with such precision. I’m thinking in particular of the skin crinkled around your stepfather’s half-shut eyes and his hot boozy breath, intimate descriptions such as these. How difficult was it to return to these moments and sink in so deeply?

Very difficult. Especially when I was working on the last revisions for the essay. I definitely had to take breaks, walk away from my computer and do something happy—listen to music or watch a funny show. Get my mind out of the space for a while, because it’s easy to descend back into how you felt in that time.

I also want to mention, that specificity is really inspired by one of my writing mentors, Jo Ann Beard. Jo Ann is the master of the most specific details, I’m thinking in particular of an essay she wrote called “The Fourth State of Matter,” where she describes the Milky Way as “a long smear on the sky, like something erased on a blackboard.” The fact that you said precision really made my day because that is what I’m aiming for when I’m writing. I want the reader to feel like they’re there with me.

I attended a Master Class at NYU with Mary Karr and she talked about how in memoir the reader wants to see you as an avatar so that they can live through your experience. That’s also something I think about when writing.

When you reenter these moments, do you reenter the anxiety, fear and depression that were going on or are you able to have some distance from that?

Both. Sometimes I do renter those feelings, but something that comes with time is the ability to see yourself as a character. You’re looking back with the eye of a writer kind of watching over your life as it was lived.

You go to your body a lot in your writing: “The words feel like hot coals in my mouth, heavy and shame-ridden” or the dresser drawer knobs digging into your back that ground you as you sit in your childhood room writing. Is this because your body is where these experiences live?

Absolutely. That was something I learned from studying with Lidia Yuknavitch who is just incredible and someone who has changed the way I think about writing. She teaches corporeal writing. You can’t write about something that happened to you without acknowledging your physical presence because your body is part of the story.

You were on a fantastic panel at AWP called “Writing the Mother Wound.” Rene Denfeld, also a panelist, suggested we take away the shame of being a “bad mother” so that the women who need it can get help. Do you agree with this? If so, how do we go about doing this?

Rene is brilliant, and I loved that comment and the whole panel. Vanessa Mártir (who curated and moderated) has created a movement with the classes she teaches on the mother wound. Shame causes silence and silence can be toxic. The subtitle of my book is Fifteen Writers Break the Silence. It’s important to talk about stuff that we have shame around including if a mother has messed up. Why can’t we talk about that? Why is there so much shame? Why is there so much guilt? Part of the guilt often comes from feeling very alone whether that comes from the child who had a bad mom or the mother herself. So why can’t we talk about the uglier things, too? We need to be able to break all kinds of silences. And shame is often where some of our most important stories revolve around, so we need to get the heart of that.

How do you feel now that you’ve spoken your truth and your truth has landed your book on pretty much every Most Anticipated list along with one starred review after another from Kirkus to Library Journal and call-outs in Time, Entertainment Weekly, Esquire, Elle, and the BBC? The list goes on.

I’m incredibly grateful this book is getting the attention it is. I think it’s because of the talented writers and because the topic is universal. But I’m not going to lie, it’s also terrifying to have one of your most vulnerable stories out there in the world, immortalized in a book with other writers I admire which feels a little different than just publishing it as an essay.

Can you articulate what’s scary about that?

I guess it’s that I’m revealing something so deeply personal, that has caused me so much pain. Yet I’ve also gained some inner strength and conviction from writing about this, and from the fact that it has resonated with other people.

Do you have any advice for writers who want to write the truth of their experiences, but have concerns about potentially hurting others?

I think the main thing when you’re writing something so deeply personal is that you can’t think about your audience. You have to write the draft like no one else will ever read it. Because if you think about what anyone else will say, you’re going to paralyze yourself. You’re going to silence yourself from the get-go. Get that first draft on the page and see where you’re at. But very likely if this is a story the writer is having a hard time telling, it’s going to take multiple drafts to realize what they’re actually writing about.

The other thing is to put the writing aside for a while and come back to it when you’re in a different frame of mind.

How do you think your life might have been different if your mom had stood by you?

It’s hard to say. As a writer I’m always thinking about different paths. Different ways my life could have gone. But I think I’m where I belong.

Jane Ratcliffe’s work has appeared in O, The Oprah Magazine, the Sun, Longreads, Tin House, Guernica, Narratively, Michigan Quarterly Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Columbia. She’s just finished a novel about the unpopular peace movement as well as the burgeoning women’s movement in London during WWII.