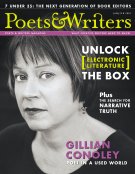

Gillian conoley is a poet writing in a used world. Every image, object, word, and sound has been manufactured, recorded, duplicated, duplicated again, and strategically delivered to a public numb with information. The influence of advertising—hurtling down wide, ever-expanding bands of media—continually chips away at individuality. What remains is the detritus of a culture obsessed with complete and total media domination. All objects are transformed. An apple is no longer an apple; it is the trademark of one of the biggest computer companies in the world. A cigar is no longer a cigar; it is the signature of the most widely trumpeted sex scandal in American history. A white Ford Bronco, in the wake of the 20th century’s most publicized criminal trial, takes on colossal significance; it is the symbol of murder and media gluttony that O.J. Simpson rode down the California freeway.

Although this struggle between the individual and media culture has intensified in the 21st century—technological advances have certainly speeded up the process—it is a timeless one. After all, Eve changed the way we perceive an apple, Freud gave a whole new meaning to the cigar, and Ford Motor Company tamed the wild horse.

In such a saturated culture, how can a poet clear away uninfluenced space from which to write a poem that is authentic, original?

![]()

Gillian Conoley has been clearing away such a place for the last two decades. An associate professor at Sonoma State University, Conoley has written four books of poetry, all published by Carnegie Mellon University Press. Her first, Some Gangster Pain (1987), explores the arid Texas plains on which she was raised. “The sea left this place / to fend for its own water, / leaving prickly wind / and one yellow color. // Birth continued.” These first poems speak through a voice that is at once tender (“Tonight I feel mortal, / like I could never grow another arm / the other two could love”) and jagged, with the customary twang of a country-and-western singer (“I may be walking backwards onto this plane, / but you’re looking / like some rat-eyed pimp, / some hillside jack on the slide”).

With her subsequent books—Tall Stranger (1991) and Beckon (1996)—Conoley departs from the familiar Texas of her childhood, but retains a sense of its wide-open plains, and incorporates it into her poems in the form of white space. Using a powerfully compressed style that filters language through an acute sensibility, she elevates the word above the media blitz and technological blur in order to explore the uncertainties of the modern world. “What is beautiful? What is ugly? / What is Country? Liberty? Honor? / We returned home alone, / to improvise, on the piano.” Conoley consistently negotiates the complex relationship between identity and culture, and her latest book, Lovers in the Used World (2001), is no exception. With language pulled taut, Conoley engages in the struggle to deliver words from the shackles of consumer-driven rhetoric.

What if there is not enough nothing?

The real black humor being that we’d filled it.A naked I a fully clothed I

Culture is my hairshirt

It’s no wonder that Conoley, a warm yet private woman, has taken this struggle with cultural influence and made it the focus of her latest book. Behind the deep brown eyes, under the soft Southern drawl that habitually slips into laughter, she cradles a quiet, unassuming manner that doesn’t quite match the high-tech times. “I spend a lot of effort trying to block out the information of the Information Age because I crave privacy so much,” she says. One of the ways she has accomplished this is by avoiding television—she doesn’t own one. She got rid of it during the media circus that accompanied the O.J. Simpson trial in the mid-1990s. “I kept having too many weird dreams, and I resented having O.J. Simpson in my consciousness because of TV,” she says.

Conoley grew up with some distance from the influence of media. She was born in Taylor, Texas, a small town near Austin, around the time television was becoming a household word. But Taylor in 1955 was a far cry from the media-saturated culture of today. Her father was the owner and manager of the local radio station, ktae, for most of his life. (Lovers in the Used World is dedicated to his memory; he died last July at the age of 79.) “The whole sense of community was what was real attractive to him about a radio station,” she says. “He didn’t even like music.” Country-and-western, Mexican polka, soul, rhythm and blues—her father would have none of it. When he came home from the station, which broadcast from six in the morning until six at night, the family would turn off the music. He saw the role of ktae as that of a small-town newspaper entrusted to disseminate vital information to Taylor’s ten thousand listeners. “It broadcast community news, like if somebody’s cow got loose,” Conoley says.

The insular world of Taylor exists in stark contrast to the “global community” of the Information Age, and has provided Conoley with a unique perspective from which to write Lovers in the Used World. “Eternity flattens. And opens, // like sitting alone for a moment in a café / in a hole in the wall in the sorry chair in the middle of the dirt of the place, // then the urge to take that look off your face, / get the particular hell home.”

With little else for a girl to do in the small Texas town, Conoley spent much time listening to the stories of the townspeople—“many of them, I am sure, highly embellished,” she says. The stories she heard, and the strong sense of community they engendered, would prove to be a valuable prelude to her future education. “To know firsthand the generational lore from so many different families—there are lessons about the complexity of human nature there—is certainly something one can’t learn from psychological or philosophical texts,” she says. Conoley’s poem “The Ancestors Speak,” which appears in her first book, addresses the inherited knowledge, the narratives handed down from generations past without the aid of streaming audio or QuickTime players.

If whatever ends with beginning

By ending begins, help our storyTake hold. We’ll strut our whole selves

Inside you, stomp our sentence

In your mouth.

To the oral narratives of relatives and neighbors, Conoley added the experience of reading books harvested from a rich tradition of Southern literature. Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty, Truman Capote, and William Faulkner wrote of characters familiar to her, voices Conoley associated with Taylor and the people who shaped her sensibility. “The syntax, the intonations of speech, the phrasing, the lazy wandering narrative, the characterizations [were] all a great comfort to me to read.” The work of these Southern literary masters expanded the borders of her small town without violating the tight connection she felt to it.

The sense of community in Taylor nurtured Conoley through her childhood, but eventually her mind reached beyond the constrictive city limits. “Of course, it was culturally bankrupt and intellectually dead,” she says. “It could be a stifling and repressive environment, and I headed off for other locales as soon as I could.” By heading off into the unknown, suddenly larger world, Conoley opened herself up to some of the major themes in her poetry: dislocation, cultural fragmentation, and the relationship between the individual and society.

One day I looked

at the face in my shoes

and walked off the land

I was raised on.

Live in one town too long,

a lush plain

grows inside you.

![]()

In 1973 Conoley moved 200 miles north to Dallas, where she received a degree in journalism at Southern Methodist University. A string of newspaper jobs followed—at the Irving Daily News, at the Dallas Morning News—but Conoley sought something more from language than could be obtained from the linearity of journalistic writing. “I don’t want to use stories that have one particular meaning, because they seem false to me. I prefer narratives that are more like fairy tales,” she says. “You can’t say exactly what it means, but there’s an enchantment of the mind.” Conoley became interested in finding a form of writing that acknowledged unexplored depths of perception, that moved beyond the falsely tidy Aristotelian narrative structure, one versatile enough to explore some essential human mystery or commune with the unknown. She was drawn to a form through which she could test the bounds of language. She was drawn to poetry.

Conoley enrolled in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where she studied with poets James Tate and Madeline DeFrees. It was here that she met her husband, the crime novelist Domenic Stansberry. After graduating, the two writers slowly made their way west, accepting teaching positions at the University of New Orleans, Tulane University, Eastern Washington University in Spokane, California State University at Hayward, and San Francisco State. Since 1994, Conoley has taught at Sonoma State University.

For Conoley, the contrast between Texas and northern California is one not only of geographical distance—from the less populated region south of Tornado Alley to Corte Madera, on the edge of Silicon Valley—but of time. Over the last half century, the speed at which the media have encroached on the individual has grown exponentially. Far beyond the radio signals of ktae and the confines of Taylor, Conoley is a witness to “Culture / invading a huge hole in the realism.”

The close proximity in which she lives to the dot-com industry of the San Francisco Bay area is ironic considering Conoley’s rejection of even the “old” technology of television. The Internet merely compounds the problem. “I find a lot of the Internet to be like television: manipulative and brain-numbing, insipid and intrusive to one’s interiority,” she says. Although she has recently succumbed to the convenience and immediacy of e-mail, Conoley is still in love with paper. “I spend much more time staring into a white page than a computer screen.”

It is on this white page that Conoley offers the experience of seeing the world unencumbered by the countless associations foisted upon it by contemporary culture, although its manifestations appear and disappear throughout Lovers in the Used World. The refuse of a throwaway culture—a red I Love Lucy kerchief, an atm card, a can of Colt .45—blows through the pages, material reminders of an immaterial world. She writes: “...we’re looking into a box. // Let’s see the world. Are you coming with me. What’s for dinner.” Conoley draws the attention of the reader away from the television and the computer—the glowing boxes that so influence our perceptions of the world—in an impassioned plea to find meaning ourselves, as individuals: “Do not fix it in the eye—go! // Do not read it in the book—live!”

Although this imperative has become desperately difficult to heed in the 21st century, it has been the crucible for many modern writers. Those to whom Conoley has listened carefully—Gertrude Stein and James Agee among them—also encountered the difficulty of negotiating the complex relationship between culture and identity. “It seems as though in order for there to be an authentic self in our culture, you have to shave yourself down to a place of no identity,” she says.

In 1914 Stein wrote Tender Buttons, a book of poems that attempted to shake words of their cultural associations, thereby ridding the poet—and the objects she wrote about—of identity. Much of the collection is written in a form evocative of dictionary definitions; Stein’s “entry” for “A Dog” reads, “A little monkey goes like a donkey that means to say that means to say that more sighs last goes. Leave with it. A little monkey goes like a donkey.” William Carlos Williams described Stein’s writing as “going systematically to work smashing every connotation that words ever had, in order to get them back clean.”

Agee struggled with writing as a form of representation in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his classic portrait of three Southern tenant-farmer families, published in 1941. “A piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point,” he wrote in his preface to the book. His intense race and class guilt fueled the notion that representing something with words—instead of presenting the thing itself—essentially diluted its original essence.

“So much comes to us already used, already represented so many times, so copied, that the effort of seeing something in its original state is so difficult,” Conoley says from her 21st-century vantage point. In this used world, Conoley finds meaning that is worth being salvaged from words that have been covered by thick layers of cultural associations. “I want to write to a place where language breaks down,” she says. When language breaks down, words, liberated from their worn connotations, come nearer to expressing the ineffable qualities of the human experience.

![]()

On November 10, 1992, an event changed the way Conoley framed her life—a singular event the significance of which words so often fail to articulate: Her daughter, Gillis, was born. “Upon the birth of my child, I thought then and still do that there was a great psychic deepening,” Conoley says. “I experienced a clarity of what I wanted to do with my life, and I knew more strongly than ever that what I wanted to do was write.”

During the long months of her pregnancy, Conoley found the potent mix of hormones and forced inactivity to be a less than ideal recipe for writing poems (“It made me stupid,” she says, laughing), so she turned to the parallel activity of editing a literary magazine. Volt was born. Published annually by the nonprofit Pacific Film & Literary Organization (founded by Conoley and her husband), with help in the form of grants from Sonoma State University, Volt is at heart a grassroots operation. Conoley edits the poetry and her husband edits the fiction.

Volt publishes experimental poetry and prose alongside other, more traditional, modes of writing. When the first issue of Volt was published, it joined only a handful of journals with a similar aesthetic, New American Writing and Denver Quarterly among them. Eight years later, Volt can be seen as a precursor to such literary magazines as Conduit, Explosive Magazine, Fence, The Germ, Lit, Phoebe, Rhizome, and Verse—all of which publish avant-garde work without excluding other writing. “Each literary magazine forms a kind of community, however tentative, however transitory,” Conoley says. “Particularly for poetry, the literary magazine is crucial for the survival of this kind of community. I’m not talking about the marketing of a particular aesthetic. Magazines get our work in the hands of the like-minded.” One of the most striking aspects of Volt is its size: The pages are nearly 14 inches from top to bottom. Its dimensions provide for more white space than does the typical magazine “so the poem can float in it a little,” Conoley says.

Though published in the traditional trade paperback format, Lovers in the Used World also uses white space to provide moments of silence. “I find myself very attracted to poetry that has a lot of white space lately,” she says. “I find that sort of work restful. Not to have a page covered with words is somehow more inviting. I want to go into that world.”

In Lovers in the Used World, Conoley offers the reader the opportunity to go into that world and experience moments of silence as a respite from the clutter of our digital culture: the familiar screech of the computer’s modem, the sound bites, the advertising jingles. It is a comfort we are not often afforded. “What if there is not enough nothing?” Conoley asks in one of the book’s early lines. By the last poem, her words slow to a trickle until there is precisely that:

silence throwing itself asunder spectre joyous

Some are born

who find use

use some of this

use this

Kevin Larimer is the assistant editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.