In our Craft Capsule series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 222.

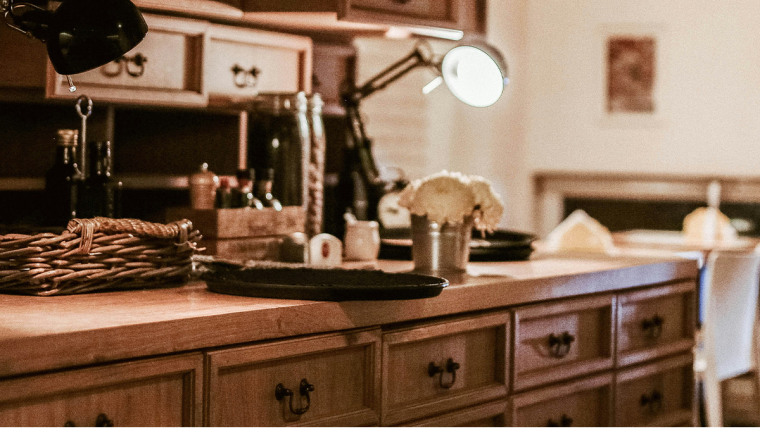

As a character in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse urges, “Think of a kitchen table then…when you’re not there.” I’ve been unable to stop thinking about this and other kitchen tables since. From Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series of photographs to Chang-rae Lee’s portrait of his mother through her cooking in “Coming Home Again,” kitchens offer an especially satisfying glance at family life. Now that another holiday season has come and gone, and with it the cluttered joy of too many cooks, Joan Didion’s words come back to me from her essay “On Going Home”: “Paralyzed by the neurotic lassitude engendered by meeting one’s past at every turn, around every corner, inside every cupboard, I go aimlessly from room to room. I decide to meet it head-on and clean out a drawer….” Arraying the contents of the drawer before the reader, Didion offers us a family portrait via this scattershot curation, a paragraph that becomes an inset narrative diorama, a Joseph Cornell box in a family’s drawer.

Like Woolf’s kitchen table, Didion’s drawer compels me to keep thinking about it. I picture my parents’ kitchen drawer when nobody is there, the sticky feel of its pull slowed by decades of accreted paint and cooking oil. I see their stash of takeout chopsticks, scraps of paper with my sister’s handwriting, holiday cards from their students of yore, keys that no longer unlock doors. Picturing this drawer and the feelings it evokes, Kay Ryan’s poem “Things Shouldn’t Be So Hard” comes to mind. Ryan contemplates someone who is now gone, “where she used to / stand before the sink, / a worn-out place; / beneath her hand / the china knobs / rubbed down to / white pastilles,” and then demands: “Her things should / keep her marks. / The passage / of a life should show; / it should abrade.”

What do inadvertent assemblages of family life tell us? How do they offer revealing family portraits in their miniature museums? In asking students in my Writing About Family course to craft a piece on “Place,” we start contrastingly big. I ask them to consider the sweeping aerial views of Jhumpa Lahiri’s account of returning home in “Rhode Island,” the opening illustrated map in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Beautiful Struggle (One World, 2008), Alison Bechdel’s intricate cartography in Fun Home (Mariner Books Classics, 2007). After thinking about home from a bird’s-eye view, I then ask students to adopt a smaller scale, a closeness of vision. Create a family portrait by describing a kitchen drawer. In urging students to depict family via one household drawer, I ask them to think about how pockets of place can convey a larger sense of home. The experience of opening a family drawer to a reader’s view, exposing its bric-a-brac or manicured minutiae, can reveal a great deal: the unwitting and the cherished, the discarded and the kept, the hidden in the mundane, contradiction and unease, or to borrow Kay Ryan’s words, what the passage of a life should show.

Rebecca Rainof is a writer and scholar on the faculty in English at the University of California in Berkeley.

image credit: Eduard Militaru