Robin Lampman is a published poet and an educator with thirty-five years of experience teaching in universities, high schools, and elementary schools. She received a master’s degree in Bilingual Education and has taught literature in two languages in public schools in New Mexico, Texas, and New York, as well as at the University of Monterrey in Mexico and the American School of Madrid in Spain. Lampman published a volume of poetry by eighth graders in Harlem, which was made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts’ NEA Big Read grant. For the last several years she has been teaching writing classes for the Noble Maritime Collection including adult classes on poetic forms and food literature. Cooking the Books, an anthology which includes recipes, poetry, essays, and memories relived by her students is available at the Noble Maritime Museum. Lampman is the literary chairperson for the Staten Island Creative Community and organizes their Second Sunday Spoken Word events, and publishes the Staten Island Creative Community Journal of Literature and Art.

As a poet and educator who has been teaching literature and promoting poetry at schools and museums in New York and New Mexico, as well as in Mexico and Spain, I have always been on the lookout for ways to give poets a voice. Several years ago, I began serving as the Literary Chairperson for the Staten Island Creative Community and organizing Second Sunday Spoken Word events in Staten Island, New York.

In June of 2015, the event was attended by ten poets, and we were each other’s audience. In February 2016, we received the first of four Readings & Workshops grants. Since then we have been able to fund a poet who once lived in Staten Island but now lives in Manhattan, a poet who writes in both English and Spanish, and a poet who writes in both Japanese and English. Our audience as well as our pool of writers has grown.

In June of 2015, the event was attended by ten poets, and we were each other’s audience. In February 2016, we received the first of four Readings & Workshops grants. Since then we have been able to fund a poet who once lived in Staten Island but now lives in Manhattan, a poet who writes in both English and Spanish, and a poet who writes in both Japanese and English. Our audience as well as our pool of writers has grown.

We have hosted readings at the Makers Space, the Hub, the St. George Day Festival, and the National Lighthouse Museum. We will be reading at the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition in the spring. But to fully understand the impact that Poets & Writers has had on us, you must let me describe our last event to you.

On the eighth of January, the day after the first snowstorm of 2017, Second Sunday Spoken Word was scheduled to present “Poetry in Many Languages.” Though the snow had subsided, the streets were still white and the temperature was frigid. We wondered who would brave the streets to read a poem. We wondered if anyone would come out in the cold to listen to poetry, much less poetry read bilingually.

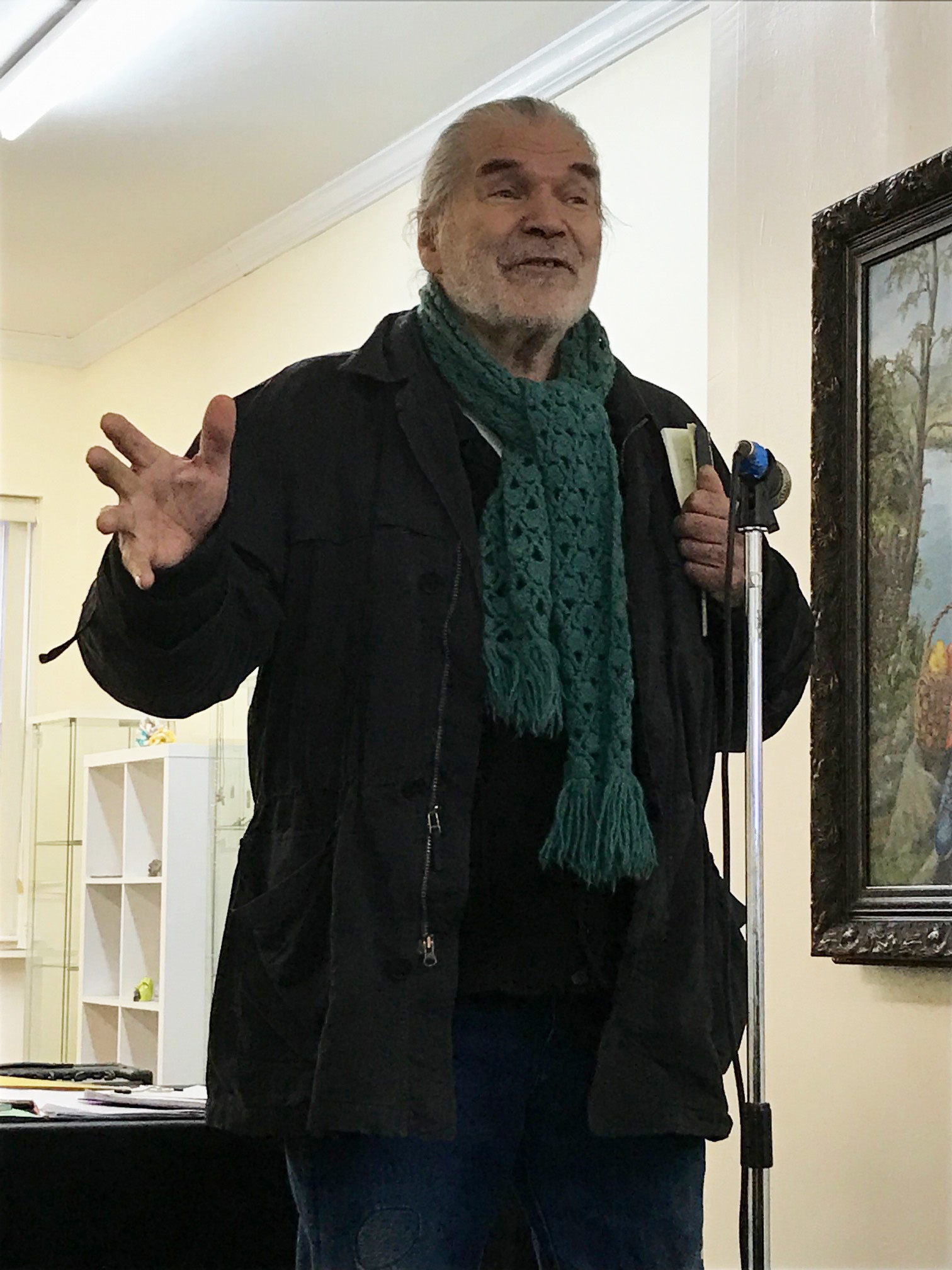

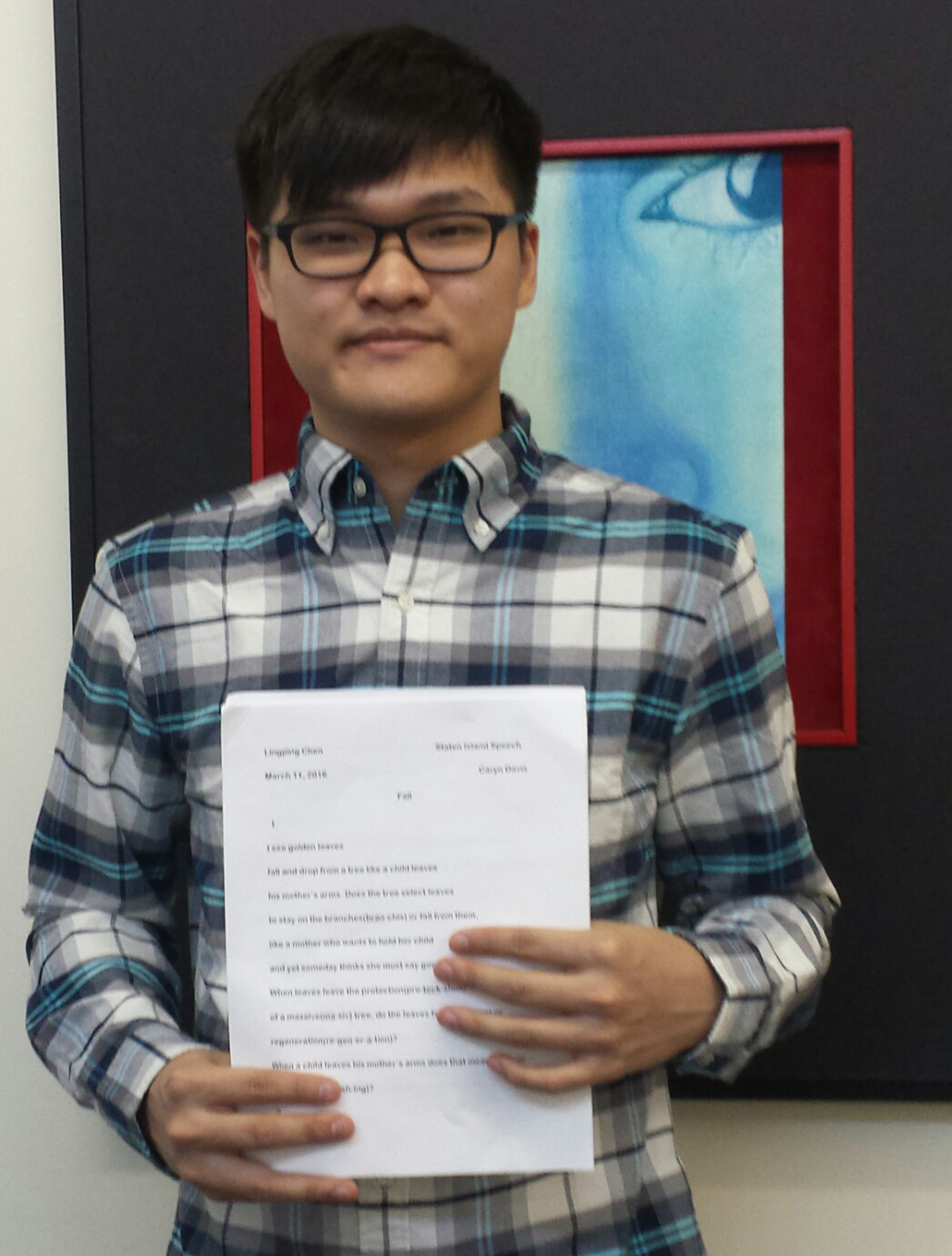

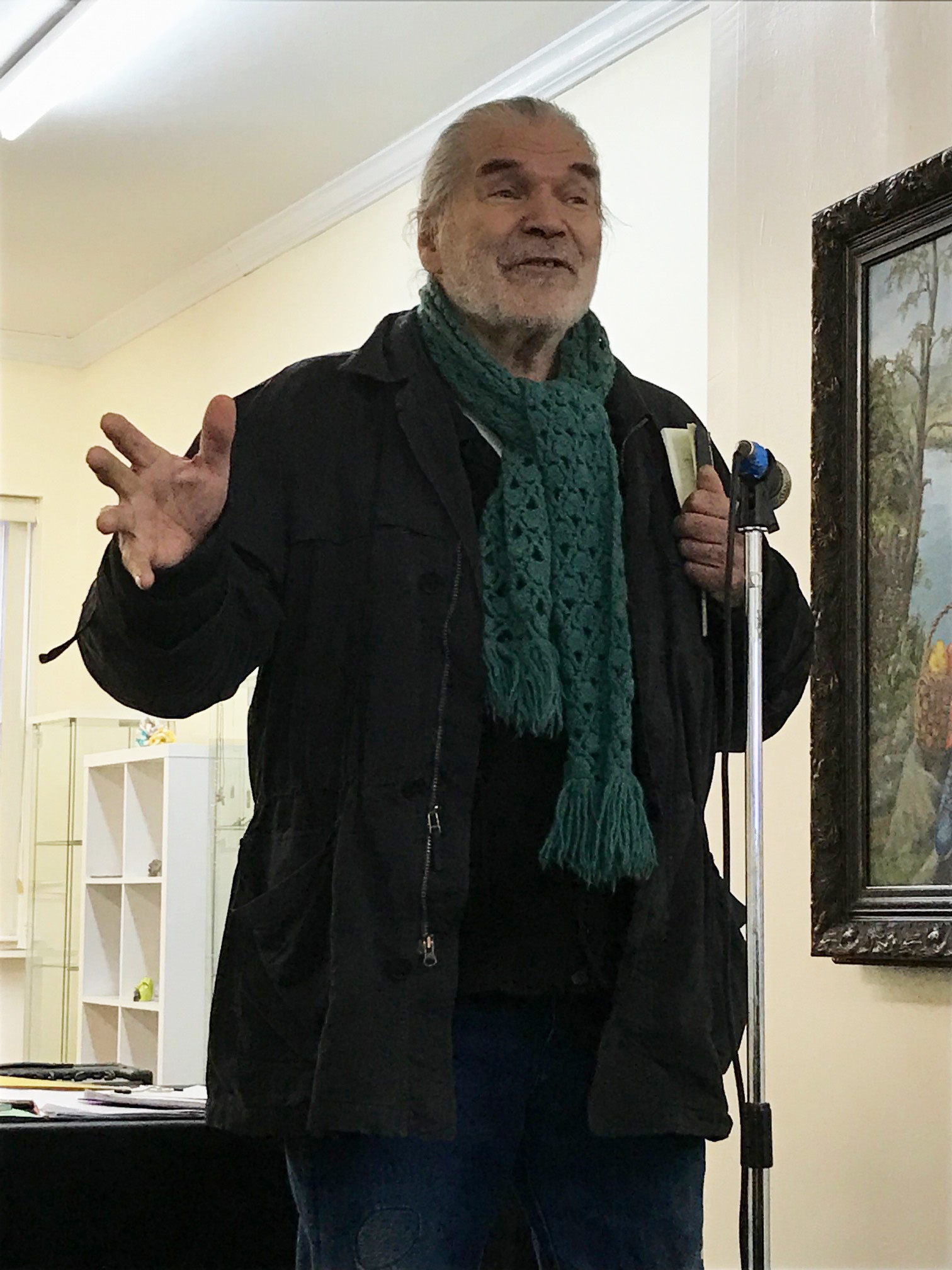

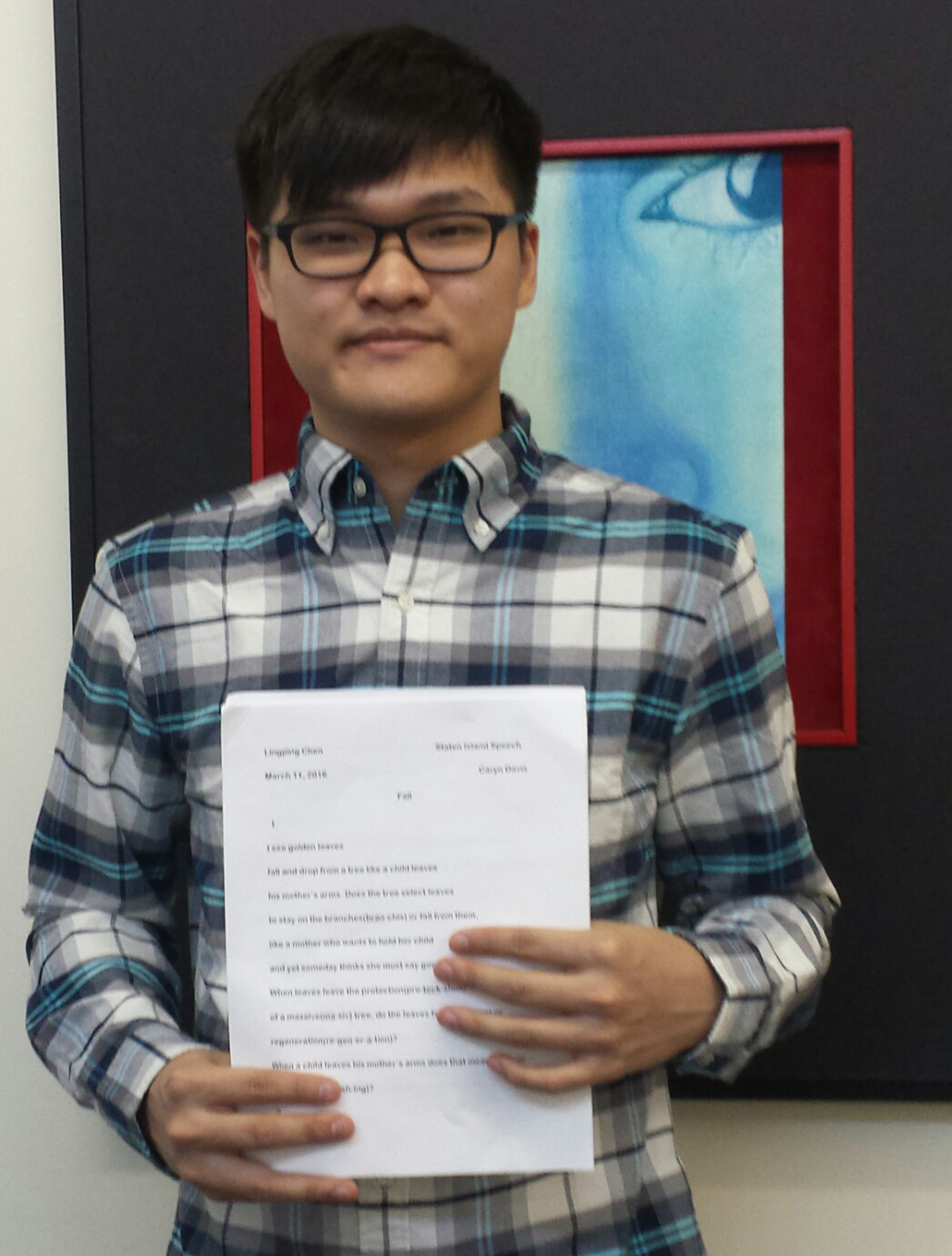

At 2:00 PM the gallery was empty. We shoveled the sidewalk and salted the ramp. An hour later, the gallery was full. Marilyn Kiss read in Spanish, Kevyn Fairchild in Hungarian, Malachi McCormick in Irish, Dominic Ambrose in Italian, Lorenzo Hail in French, and Lingping Chen, who had come in on the ferry, read in Chinese.

At 2:00 PM the gallery was empty. We shoveled the sidewalk and salted the ramp. An hour later, the gallery was full. Marilyn Kiss read in Spanish, Kevyn Fairchild in Hungarian, Malachi McCormick in Irish, Dominic Ambrose in Italian, Lorenzo Hail in French, and Lingping Chen, who had come in on the ferry, read in Chinese.

Henry Van Campen, recipient of the R&W grant for this event, read from his new book, Internal Externals, in both Japanese and English. Hiroki Otani concluded the event singing original lyrics in Japanese. We all sang along. “Ganbaro,” we sang. “Hello, goodbye, and take courage.”

Who braves the storm to read a poem? Who braves the storm to hear poetry in many languages? It is a testament not only to the strength that support from Poets & Writers has given Second Sunday Spoken Word in Staten Island, but to the strength inherent in the diversity of New York City. It is a testament to the power of poetry.

Photo: (top) Robin Lampman at the National Lighthouse Museum. Photo credit: Michael McQueeny. (middle) Malachi McCormick recites his poems in Irish. (bottom) Lingping Chen reading in Chinese. Photo credit: Robin Lampman.

Support for the Readings & Workshops Program in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis and Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Trust, and Friends of Poets & Writers.

In June of 2015, the event was attended by ten poets, and we were each other’s audience. In February 2016, we received the first of four Readings & Workshops grants. Since then we have been able to fund a poet who once lived in Staten Island but now lives in Manhattan, a poet who writes in both English and Spanish, and a poet who writes in both Japanese and English. Our audience as well as our pool of writers has grown.

In June of 2015, the event was attended by ten poets, and we were each other’s audience. In February 2016, we received the first of four Readings & Workshops grants. Since then we have been able to fund a poet who once lived in Staten Island but now lives in Manhattan, a poet who writes in both English and Spanish, and a poet who writes in both Japanese and English. Our audience as well as our pool of writers has grown. At 2:00 PM the gallery was empty. We shoveled the sidewalk and salted the ramp. An hour later, the gallery was full. Marilyn Kiss read in Spanish, Kevyn Fairchild in Hungarian, Malachi McCormick in Irish, Dominic Ambrose in Italian, Lorenzo Hail in French, and Lingping Chen, who had come in on the ferry, read in Chinese.

At 2:00 PM the gallery was empty. We shoveled the sidewalk and salted the ramp. An hour later, the gallery was full. Marilyn Kiss read in Spanish, Kevyn Fairchild in Hungarian, Malachi McCormick in Irish, Dominic Ambrose in Italian, Lorenzo Hail in French, and Lingping Chen, who had come in on the ferry, read in Chinese.

Now, I am in New York City. I am excited and terrified. I have just arrived on the red-eye into JFK.

Now, I am in New York City. I am excited and terrified. I have just arrived on the red-eye into JFK.  Alicia meets me at the hotel. We cab to Chinatown and eat an amazing lunch. We sightsee before heading back to the hotel for our initial meeting with Bonnie Rose Marcus and Wo Chan, who work in the Readings & Workshops (East) department at Poets & Writers.

Alicia meets me at the hotel. We cab to Chinatown and eat an amazing lunch. We sightsee before heading back to the hotel for our initial meeting with Bonnie Rose Marcus and Wo Chan, who work in the Readings & Workshops (East) department at Poets & Writers.