Idle Hands are the Poet’s Playground: Brendan Constantine on Taking a Chance

Brendan Constantine, September’s Writer in Residence, was born in 1967 and named after Irish playwright Brendan Behan. An ardent supporter of Southern California’s poetry communities, he is one of the region’s most recognized authors. He is currently poet-in-residence at the Windward School and regularly conducts workshops in hospitals, foster homes, and with the Art of Elysium. His latest collections of poetry are Birthday Girl With Possum (2011 Write Bloody Publishing) and Calamity Joe (2012 Red Hen Press). He lives in Hollywood, California, at Bela Lugosi’s last address.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

My relationship with Poets & Writers began in 1995 when I first sought their help in paying authors to read for a local series, the Valley Contemporary Poets. In the years since, their support—both financial and creative—has enabled me to build a whole career. I’m sure you can appreciate how daunting it is, then, to try to write something “worthy.” At every keystroke I imagine someone at the P&W main office looking up from a computer and saying, “Wait, we’ve PAID this guy to give readings?”

Of course, it’s just the same old vanity that plagues every writer: the Phantom of Originality, also known as the Tenth Muse. Not only is originality a false god, history has made it plain there are no profundities so great they cannot be trivialized; death is a business, so are babies, and now Webster’s definition of “reality” includes the subheading “a genre of television.” If nothing is sacred, neither is writing.

Exactly ninety years before the date this blog will appear, a writer named Richard le Gallienne wrote a New York Times review of four new books of poetry. Before addressing any of the titles, he observes, “Unless poetry is as compelling as Ragtime, we labor in vain to read it.”

Ragtime. Join me for a deep sigh, would you?

For those of you who’ve ever felt as though your art has too much with which to compete in popular media, that it’s no match for TV, movies, or popular music, the above quote should offer some comfort. Ragtime may have topped the charts of 1922, but a good deal of transcendent writing came after, indeed most of what we call Modern poetry. Give yourself a break.

Speaking of taking a break, in Samuel Johnson’s essay “The Rambler,” he contends, “It is certain that any wild wish or vain imagination never takes such firm possession of the mind, as when it is found empty and unoccupied….” He is praising activity for its own sake, warning against the hazards of idleness. What are the hazards? Depression, melancholy, and, even worse, posthumous notoriety.

But for writers, the value of “down time,” with nothing on our minds but the cookie in our hands, is priceless. There’s no telling what combination of whim and weariness will send us into despair or creative action. But perhaps they’re the same. To be an artist is to create “stillnesses”—the stillness of the page, the plinth, and the canvas, the thousand stillnesses in one minute of film. Or dance.

To be an artist is to invite “any wild wish or vain imagination” to take firm possession of our minds, to dare boredom to do its worst, to take second place to Ragtime.

Furthermore, it will always be true that our poorest work lies ahead of us. We’re going to write something truly awful in the future. We have to. Why do we have to? It’s often the only way to uncover the good writing. Like going through a kitchen drawer, sometimes we have to take out things we don’t need in order to get at the things we do.

Ask yourself about the conditions under which you’ve done your best work so far. Did you start with a defined vision and follow it to the end without deviation? I’m guessing, No.

Where I see many of us get stuck, again and again, is in forgetting the role of “chance.” No sooner are we enjoying a sense of success (even if it’s just saying “Well, that didn’t TOTALLY suck.”) than we are forgetting the experience of discovering our art as we went.

Chances are (sorry), we’ll attempt to create something else, but this time out of sheer will. Under these conditions, we’re totally screwed. Excuse me, Ragtimed. The best we can hope for is something almost as good as we used to be.

I think the answer is to just create, create a lot, make lots of mistakes, finish a bunch of lousy work, emphasis on “finish,” but get it all the way out. Make something. Make anything. Buy a children’s paint set. Get an airplane model. Make a list of the times and conditions under which someone says “awesome” and then set it to music. Something with piano and trumpets, a trombone and snare drum. Write about a room where someone is dancing to it, someone who knows it’s stupid and dances anyway.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

If only I could embrace the maxim I use in the classroom: Writer’s Block is almost never a deficit of magic but a surplus of judgment. I believe this, I do, but I'm still stuck. This is particularly ironic because what I want to talk about is Speechlessness; a speechless woman and a speechless universe. Maybe I can get this rolling if I work backwards and start with the universe.

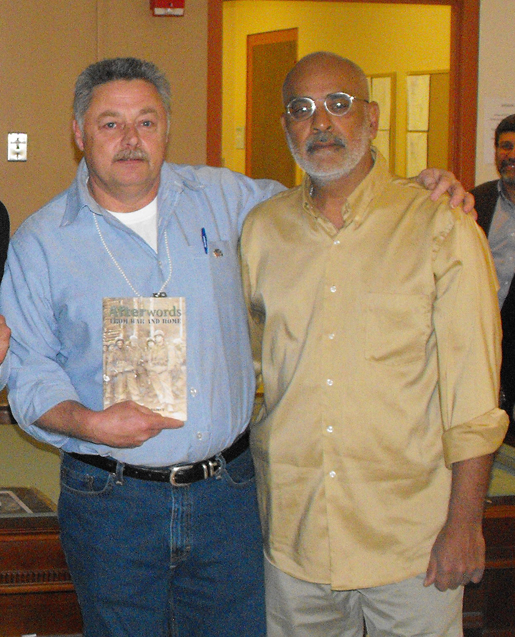

If only I could embrace the maxim I use in the classroom: Writer’s Block is almost never a deficit of magic but a surplus of judgment. I believe this, I do, but I'm still stuck. This is particularly ironic because what I want to talk about is Speechlessness; a speechless woman and a speechless universe. Maybe I can get this rolling if I work backwards and start with the universe. Dances With Wordz: Orisha Poetry, curated by Latinos NYC founder and CEO Raul K. Rios, featured performances celebrating the Yuroba faith of West Africa. The poets, garbed in white from head to toe, were an immaculate presence inside the

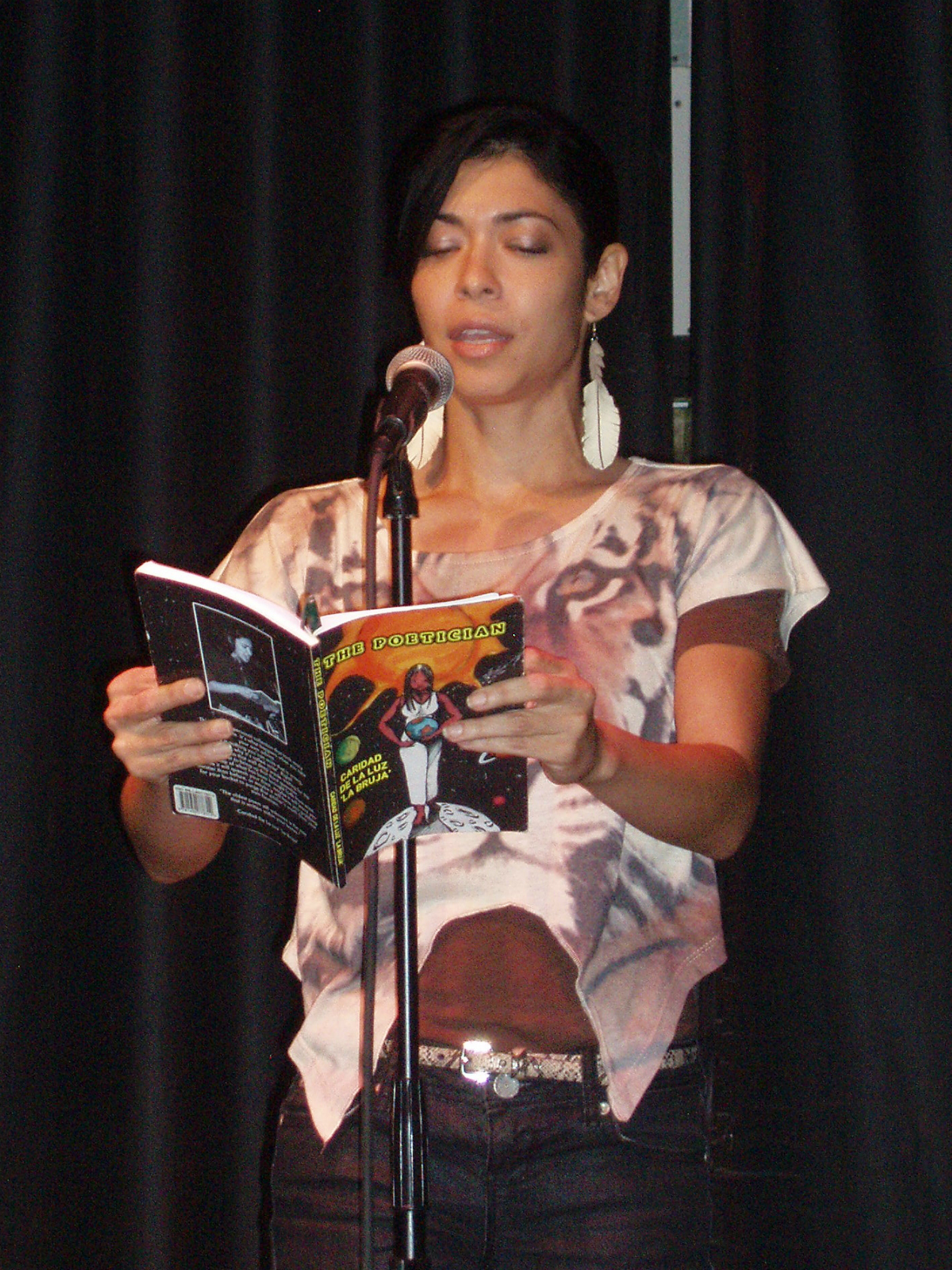

Dances With Wordz: Orisha Poetry, curated by Latinos NYC founder and CEO Raul K. Rios, featured performances celebrating the Yuroba faith of West Africa. The poets, garbed in white from head to toe, were an immaculate presence inside the  Nuyorican darling Caridad “La Bruja” De La Luz read from her first collection, The Poetician, then proceeded to rap and sing after reciting what she fondly called “straight up poetry.” Writer, actor, and painter Iya Ibo Mandingo performed last, conjuring images of home: luscious mangoes and coconuts. He ended his performance with a declarative poem, inciting reactions from the audience, which ranged from the gleeful to the guttural.

Nuyorican darling Caridad “La Bruja” De La Luz read from her first collection, The Poetician, then proceeded to rap and sing after reciting what she fondly called “straight up poetry.” Writer, actor, and painter Iya Ibo Mandingo performed last, conjuring images of home: luscious mangoes and coconuts. He ended his performance with a declarative poem, inciting reactions from the audience, which ranged from the gleeful to the guttural.