Take Two

Take two lines you love from a poem that isn’t working. Write a new poem using one as the first line and the other as the last line. For an added perspective, try writing a second poem switching the two.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

Take two lines you love from a poem that isn’t working. Write a new poem using one as the first line and the other as the last line. For an added perspective, try writing a second poem switching the two.

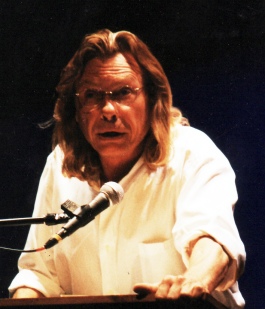

Thomas Lux blogs about his P&W-funded reading with Jon Sands for Page Meets Stage, a reading series in New York City. Lux is Bourne Professor of Poetry at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He has two new books out this fall—the poetry collection Child Made of Sand (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and his nonfiction debut From the Southland (Marick Press).

I’d heard Jon Sands read and perform a few years earlier at Sarah Lawrence College. The budget for readings was always meager and P&W has helped out several times. I believe P&W kicked in for a tribute to Muriel Rukeyser, not long before she died.

I’d heard Jon Sands read and perform a few years earlier at Sarah Lawrence College. The budget for readings was always meager and P&W has helped out several times. I believe P&W kicked in for a tribute to Muriel Rukeyser, not long before she died.

Page Meets Stage was started by Taylor Mali and others, several years ago, and was originally called Page Versus Stage. It’s now called Page Meets Stage. “Versus” sounded like an unfair fight to me—page poets are mostly older and would get our asses kicked by the stage poets, who are generally younger, and kick ass anyway, just for fun. So they changed the name. I contend, however, that the people there weren’t concerned with what it was called—they were there for poetry.

I’d read in the program several years before with Marty McConnell, a stunning spoken word/poet, at the storied Bowery Poetry Club, started by Bob Holman, an éminence grise of the spoken word/poet poetry world.

On September 19th, Page Meets Stage held its reading, for the first time ever, at that miracle place, Poets House. It’s in the Battery (as I write this, Storm Sandy is expected to hit the Battery hard) and not too far from Ground Zero. It’s brand new and has two floors filled with poetry books, over 50,000 of them! They also offer many outreach programs and are completely inclusive. They even have sleepovers. Borges said something like: “I can only sleep in a room filled with books.” At Poets House he’d sleep like a big fat baby! It exists, in a nutshell, to serve the art form of poetry. Recently, a student considering taking a class of mine wrote asking for a copy of my syllabus. I wrote back: “Go to NYC, go to Poets House, find the exact center of it, stand there, and turn around 360 degrees. That’s my syllabus.” He responded not.

I often ask Taylor (a premier spoken word/poet): What the bleep’s the difference? Only one, and it’s not even a rule: spoken word/poets tend to memorize their poems. All poets have to write first, on a page, or on a screen, and—this shouldn’t come as a surprise—it’s hard to write well. Page poets give readings; spoken word/poets give readings but tend to call them “performances.” Some stage poets are breathtakingly self-indulgent, some page poets lay on the pseudo-profundity so much I can only hope someday someone translates them into readable English! Taylor usually gives an erudite and nuanced answer to my question.

I still don’t see much difference. It was a larger, younger, more boisterous crowd than the night before at the gallery. Sands is an excellent young spoken word/poet, and his delivery is intense. He leans slightly forward, almost as if he’s walking into a strong wind, and speaks his poems. No histrionics, little body movement—he held the audience with every syllable. We read alternately, trying to bounce poems off each other. It was a blast. Let me put it this way: do not badmouth, or say anything supercilious, around me re: performance poetry. It’s likely I’d fall asleep right in your face.

Photo: Thomas Lux.

Support for Readings/Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, The Cowles Charitable Trust, the Abbey K. Starr Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

American fiction writer Maggie Shipstead was recently named the winner of the 2012 Dylan Thomas Prize for young writers, an annual award of £30,000 (approximately $48,000) given by the University of Wales to a writer under the age of thirty.

Shipstead, twenty-eight, won the prize for her debut novel, Seating Arrangements (Knopf, 2012). A graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and former Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford, she lives in Coronado, California.

About Seating Arrangements, which turns a satirical eye toward New England wealth and family, author and prize judge Allison Pearson says, “At the age of twenty-eight, Maggie Shipstead has imagined herself inside the head of a fifty-nine-year-old male in the grip of an erotic infatuation. This is territory that has been covered by the greats of American fiction, including John Updike and Jane Smiley. Maggie Shipstead doesn’t just follow in their footsteps; she beats a distinctive and dazzling path of her own. The world has found a remarkable, humane new voice to explain us to ourselves.”

Established in 2006, the Dylan Thomas Prize, one of the world’s largest literary prizes for young writers, is given internationally for a book written in English and published in the previous year. The shortlist for the prize also included Tom Benn for The Doll Princess (Jonathan Cape), Andrea Eames for The White Shadow (Random House), Chibundu Onuzo for The Spider King’s Daughter (Faber & Faber), and D.W. Wilson for Once You Break A Knuckle (Bloomsbury).

Previous winners include Lucy Caldwell for her novel The Meeting Point (Faber & Faber, 2011), Elyse Fenton for her poetry collection Clamour (Cleveland State University, 2010), Nam Le for his short story collection The Boat (Knopf, 2008), and Rachel Trezise, whose short story collection Fresh Apples (Parthian Books) received the inaugural prize in 2006. For more information on the Dylan Thomas Prize, visit the website.

Write an essay about your memories of Thanksgivings past, how your family celebrated the holiday and what it means to you now and why.

Write a scene for a story that takes place at the Thanksgiving day table during dinner or in the kitchen during preparations for the meal with two characters who are are angry at each other but not addressing their conflict directly.

To mark the holiday this week, make a list of things you're grateful for. Beneath each item, free-associate a list of objects. Pick ten from your lists of objects and use them to write a poem.

Thomas Lux blogs about his P&W-funded reading at Marc Straus, an art gallery in New York City. Lux is Bourne Professor of Poetry at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He has two new books out this fall—the poetry collection Child Made of Sand (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and his nonfiction debut From the Southland (Marick Press).

I’ve never written a blog before and I’ve only read a handful of them. I can use e-mail (an excellent invention), and the computer is a very a sophisticated typewriter. I remember when Poets & Writers Magazine started. I believe the early issues were stapled, short newsletters. Maybe mimeographed? Now it’s grown in range and depth and is an important read for most contemporary writers.

It was once possible to keep up with virtually all of contemporary poetry—the number of presses and literary magazines were finite, and limited to print. Books from big houses and books from independent presses (then called “small presses”) looked pretty ugly, frankly, compared to books today, because of our enormous improvements in printing technology. They're many more venues for poetry today. Poetry is showing up everywhere.

P&W recently put a few bucks in my pocket. In mid-September, I gave a reading in New York City with Marc Straus at the Marc Straus Gallery on Grand Street. I’ve known Marc for over twenty years since he took a class of mine at the 92nd Street Y. We became friends. Marc’s a medical oncologist and, with his wife, Livia, a major collector of contemporary art. Marc is also a poet. He’s published three books: One Word, Not God, and Symmetry. Many of his poems deal with his experience as an oncologist. He writes sometimes in the voice of the doctor and sometimes in the voice of a patient. Only a real poet and oncologist can write the poems he writes. He recently opened his own art gallery, directly across Grand Street from a drapery store his father owned and ran many decades ago, and where Marc worked as a child. Here’s one of his poems, "Scarlet Crown":

I met a man my age running a greenhouse.

He pointed to the pots with pride, saying

they contained a thousand separate cacti.

Not much interest in these when I started,

he said. He pointed to the barbed bristles

(glochids), the bearing cushions (areoles),

and the names of many of the 200 genera:

Brain, Button, Cow-tongue, Hot Dog, Lace,

Coral, and Silver ball. In my work,

I said, I’m burdened with such straight-

forward terms: lung cancer, lymphoma,

breast cancer, leukemia. I’d love

to switch to: Pond-lily, Star,

or Scarlet Crown. Really, he said,

pointing to other plants, named

Hatchet, Devil, Dagger, Hook, and

Snake—or perhaps a diagnosis of this:

Rat-tail, White-chin, Wooly-torch,

or Dancing Bones.

The show up at the time was by a painter, seventy-nine-year-old Charles Hinman, who’d only recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and who’d been painting in relative obscurity for decades in a rent controlled studio just a few blocks from the gallery. I like reading surrounded by art. (Note: the show was a big hit.) Afterwards, someone handed me a rather generous check from P&W. And ditto another check the next night at a Page Meets Stage reading at Poets House. I read with a spoken-word artist/poet named Jon Sands. (To be continued in the next blog post...)

Photo: Thomas Lux.

Support for Readings/Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, The Cowles Charitable Trust, the Abbey K. Starr Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

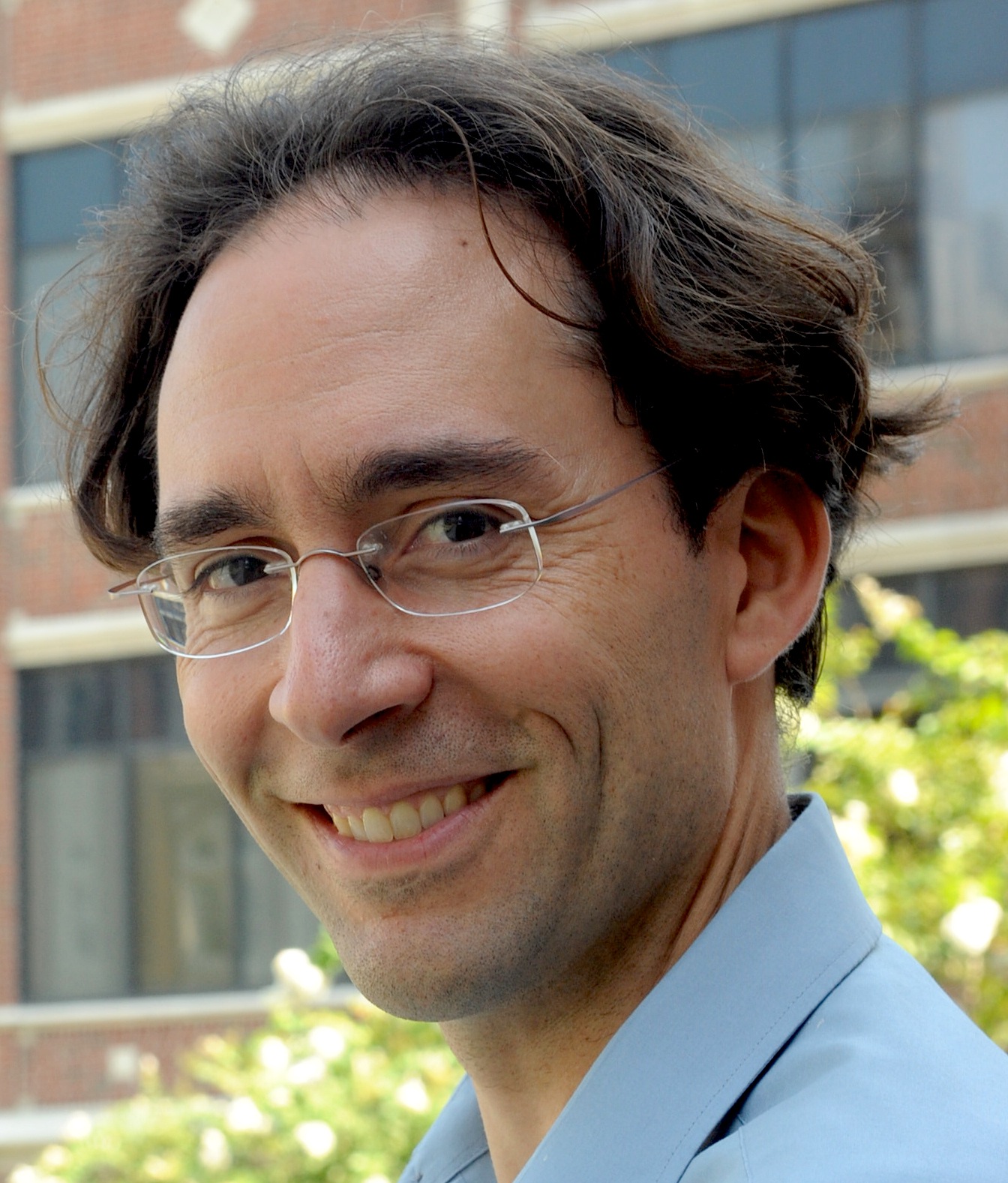

Mark Yakich's first collection, Unrelated Individuals Forming a Group Waiting to Cross (Penguin, 2004), was a winner of the National Poetry Series. His most recent collection is The Importance of Peeling Potatoes in Ukraine (Penguin, 2008). Yakich teaches at Loyola University and is editor of New Orleans Review. Poets & Writers has supported readings he’s given in both New Orleans and New York State. What are your reading dos?

What are your reading dos?

I try to prepare for a reading by having one drink beforehand. One drink loosens me up, but two makes me undress people visually in the crowd, especially small crowds where there may be only four or five pairs of eyes.

What’s the strangest comment you’ve received from an audience member?

One audience member asked after I read my poem “The Invisible Man’s Daughter”: “Who’s the invisible man’s daughter?” I didn’t really understand the question until I realized there are a lot of audience members who would like to know of such and such a poem: What’s the actual “story” behind it? This was so much the case with my first book, in which there are numerous fairy-tale-type characters, that I wrote a second book, The Making of Collateral Beauty, in order to explain the “reality” behind the poems in my first book, which I made up entirely.

What’s your crowd-pleaser, and why does it work?

From my first book, the poem “On Raisins” is the crowd-pleaser. I think almost everyone has a love-hate relationship with them. I’ll eat raisins, especially the golden ones, in a handful, but I don’t like it when raisins try to become grapes again—as when I add milk to, say, Raisin Bran and the raisins rehydrate. I just don’t believe in transubstantiation, reincarnation, or whatever it is raisins are trying to do there.

In my latest collection, the crowd-pleaser is a poem called “A Brief History of Patriotism,” which traces the history of the potato throughout a wide range of cultures, countries, and ethnicities. The problem with the poem is that people find it funny. It’s a deadly serious poem, but I don’t have the energy any more to write a book explaining that.

Ultimately, the key to pleasing an audience is to entertain, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that they have to “get” the poem. Does anybody get the meaning when they hear Gertrude Stein’s work aloud? I would argue that foremost you get entertained sonically and comically when you hear Stein; conventional meaning is not her game.

What’s the most memorable thing that’s happened at an event you’ve been part of?

The first time my nine-part poem “Green Zone New Orleans” was read aloud I was floored. I enlisted eight volunteers from the audience. Each reader, plus myself, read the sections of the poem consecutively. As soon as the last person read the last section, we all began reading our individual sections at the same time. The cacophony of voices lasted for about a minute until one by one the voices dropped out… down to three voices, then a duet, and a single voice. Audience members shocked me with their wet eyes. I was a bit choked up myself. The voices all together and then falling away reminded me of the sound of the tin cans falling away from the bumper of the car my bride-wife and I drove home from the courthouse in which we were married. We listened to those tin cans—which I’d saved over a few weeks and then tied with twine to the car in the parking lot after the ceremony—relishing their tinkle and bang against one another and the road, the violent sounds turning sweeter as each can fell to its doom.

Since that first reading, I’ve enlisted audience volunteers to read “GZNO” many times. In New Orleans, P&W sponsored my first reading from “GZNO” at Antenna, a gallery that’s part of a literary co-op and small publisher called Press Street, which also published a special chapbook of the poem.

What do you consider to be the value of literary programs for your community?

Literary readings are not revolutionary get-togethers, or get-togethers of revolutionaries. Literary readings seem, to me, more like mini-conventions of loners who feel they should get out at least once a month. Indeed, these functions always feel paradoxical to me. A text or a book is usually made by an individual alone in a room, and are mostly read alone in a room. Literary readings are public performances: lovely spots of time in which writers and poets get to connect with their, mostly, invisible readers. And in New Orleans, readings are not just readings—they are always social and increasingly they hook into neighborhood events: charter school bazaars, co-op openings, gallery walks, playground constructions, and political protests.

Before the storm there weren’t as many literary events as at present. Or maybe that’s untrue. But what I know is that the literary events now feel more communal.

Photo: Mark Yakich. Credit: Harold Baquet.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in New Orleans is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. For Readings/Workshops in New York support is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, The Cowles Charitable Trust, and the Abbey K. Starr Charitable Trust. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Write an essay about your relationship to food. Consider the following questions: Do you see food as merely sustenance or as emotional comfort? What is your favorite meal and why? Were you a picky eater as a kid? Which foods do you detest and why?

Last night at the National Book Foundation gala in New York City, novelist Louise Erdrich was named the recipient of the 2012 National Book Award in fiction. Erdrich, whose latest novel is The Round House (Harper, 2012), will receive $10,000.

This is the first National Book Award for Erdrich, 58, who over the past thirty years has authored fourteen novels and a short story collection, three books of nonfiction, and three poetry collections. The Round House, the second installment in a trilogy, follows an Ojibwe boy as he seeks to avenge his mother's rape. Erdrich, who is part Ojibwe, dedicated her award last night to "the grace and endurance of native people."

"This is a book about a huge case of injustice ongoing on reservations," she added. "Thank you for giving it a wider audience."

In nonfiction, Katherine Boo took the prize for her debut, Beyond the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity (Random House, 2012). David Ferry, whose latest collection is Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations (University of Chicago Press, 2012), won the award in poetry. William Alexander won in the young people’s literature category for his young adult novel Goblin Secrets (Margaret K. McElderry, 2012). Each winner receives $10,000.

The awards were given amid recent discussions among publishers and the National Book Foundation that the annual award—one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the United States, second perhaps only to the Pulitzer—had become too insular, and was in need of expanding its image and scope. Finalists in fiction included such names as Dave Eggers and Junot Diaz; the finalists in nonfiction included Robert Caro's Lyndon Johnson series and the late Anthony Shadid's lauded memoir House of Stone (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). Honorary prizes were also given to author Elmore Leonard and longtime New York Times publisher and chairman Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr.

Established in 1950, the National Book Awards are given annually for works of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction published in the previous year. For more information, visit the National Book Foundation website.