The stories of the debut authors featured in our fourth annual 5 Over 50 trace the unique, sometimes long, and often winding paths that lead to publication. “There’s rarely an easy path to success,” writes seventy-year-old debut memoirist Peter Kaldheim. “But as I can testify, without persistence there’s no path at all.” And while much attention is paid to how long it has taken (“What kind of nut keeps at it for twenty-seven years without success?” asks fifty-six-year-old debut novelist Julie Langsdorf), it’s important to consider that these first books would not be what they are without the experience—the joys, sorrows, struggles, and achievements—that their authors picked up along the way. These books are special for many reasons, not least of all because of the time—and patience—that went into writing and publishing them.

In our November/December 2019 print issue you can read essays by each of these five authors about their paths to publication and below you can read excerpts from each of their debut books.

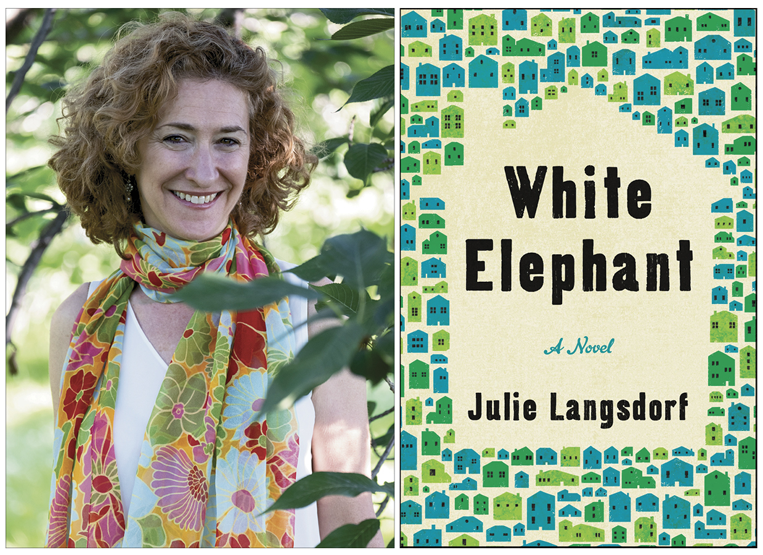

White Elephant (Ecco, March 2019) by Julie Langsdorf

Ridiculous Light (Persea Books, April 2019) by Valencia Robin

Cornelius Sky (Kaylie Jones Books, August 2019) by Timothy Brandoff

Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss (Milkweed Editions, July 2019) by Margaret Renkl

Idiot Wind (Canongate, August 2019) by Peter Kaldheim

Julie Langsdorf, author of White Elephant, published in March by Ecco. (Credit: Robin B. Langsdorf)

AUGUST 31—MORNING

Allison Miller lay in bed in the dim light of early morning thinking about sex. It was the hammering on the new house being built next door that was responsible, the rhythmic pound, pound, pounding that ought to have chipped away at any nascent amorous thoughts instead of inspiring them. She slid her hand across the sheet, touching her husband Ted’s thigh, but it was clear from the set of his mouth that sex was not in the offing this morning.

“Do you know what time it is, Al?”

The question was rhetorical. Their digital clock was of the large-numeral variety, designed for people like them, in their forties, eyes just beginning to go.

“We hardly need the alarm clock anymore, Cox is so loud,” Ted said. The revving of a chain saw made him leap out of bed as if stung. He opened the window—with effort. The Millers’ house was old and its parts had settled.

They’d lost the battle for the trees. Ted couldn’t accept it. Nick Cox, neighbor and builder, had been given the go-ahead to cut down more trees on the property next door. The town only had jurisdiction over trees that were twenty inches in diameter or more. There were a surprising number of these junior, cut-down-able-size trees on Cox’s property, a small forest that had sprung up over the years—trees not strong enough for climbing or genetically programmed to offer fruit or flowers, but still welcome for providing a little buffer of green between the Millers and the adjacent property.

Allison watched Ted with fond familiarity, the gentle curve of his rear end and the rush of red in his neck from the effort of opening the window. She waited for him to yell, to open his mouth and to really let loose. He’d threatened so many times.

She imagined Nick Cox in his jeans and hard hat, his blue eyes sparking as he yelled back. She pictured the two of them engaging in a twenty-first-century duel, fought across the yards, a battle of words over the fortress Nick was building to their left, a four-story monolith complete with battlements and a double front door that begged for attending knights in armor. It was even bigger than the faux stone castle he’d built to the right, with its many turrets and spires, where Nick, his wife, Kaye, and their two pretty blond children lived. One half-expected to see fireworks shooting into the sky above the house—if one could see the sky above from inside the Millers’, which one no longer could. Allison and Ted’s little house was wedged between the two, a pebble amid boulders.

In the meantime Tunlaw Place was in disarray, the air tinged with the stench of diesel. A construction truck and a dumpster were parked along the curb, along with Nick’s little yellow bulldozer, which looked like a brightly painted toy.

Allison closed her eyes and stretched her arms and legs toward all four corners of the bed imagining that she—not the neighborhood—was the one at stake, she the damsel in distress, she the one for whom Ted would slay Nick Cox. Or vice versa. The winner would bed her. She was ready to make the sacrifice.

Ted stood at the window, on the verge of shouting. Allison waited, excited at the prospect. Today, it was finally going to happen. Today, blood would be spilled. She took a deep breath, filling her lungs, waiting, waiting—but Ted seemed to think better of it. He slammed the window shut and stomped off to the shower.

The alarm beeped then, an unrelenting tone that increased in volume until Allison silenced it with the flat of her palm. She set off to face the last day of August. A day that was neither summer nor fall. A day neither here nor there. A day that promised to be nothing more than betwixt and between—just like she was, Allison thought. Just like her.

From the book White Elephant by Julie Langsdorf. Copyright © 2019 by Julie Langsdorf. Published on March 26, 2019 by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.