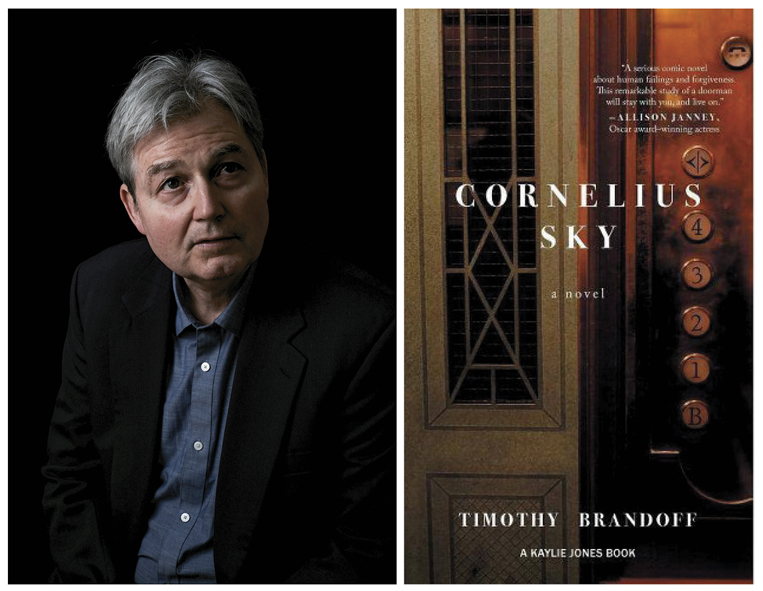

Timothy Brandoff, author of Cornelius Sky, published in August by Akashic Books. (Credit: Reuben Radding)

He sat alone in the dark, save for the snow on the television screen. He got to his feet and considered this question: how does a nonalcoholic get ready for bed? He decided to brush his teeth. He reserved toothbrushing for the morning as a rule, but given the night’s events he thought he’d brush before bed as a demonstration of his nonalcoholic nature. People of an alcoholic nature go to bed without brushing, he figured, and given the fact that he was not an alcoholic, he probably should brush. And then he thought, What else does a person who’s not an alcoholic do? His mind drew a blank. Then he thought, I know what I can do, I can prepare my clothes for the morning. I can lay my clothes out so when I wake up I know what I’m going to wear. People of nonalcoholic natures do such things. If I’m not an alcoholic, he thought, and I’m not, I can lay my clothes out like a nonalcoholic in preparation for tomorrow’s nonalcoholic day. Granted, I like to drink. Vic Morrow probably enjoys a drink himself. He got up and looked at his clothes in the closet and thought, What a strange thing to do, and decided against it. I’m not going to put my clothes out for tomorrow just to prove I’m not an alcoholic. If I’m not an alcoholic, why do I have to prove it? I don’t have to prove my nonalcoholic nature to anybody. And who would I be proving it to anyway? And even if I am an alkie, whose business is that?

They had tried to help his father, those men in suits. They came up to the house, spoke to his mother, the half-heard conversations lodged in Connie’s memory. A strange word when you’re seven years old: anonymous. Their clean-shaven faces, their pressed suits, a lucidity in the eye. Whispered words between his mother and those men, seeping through fabric hanging from doorway curtain rods, one doorless doorway after the next in those railroad flats, curtain after curtain through which muffled words floated.

Did they know Connie’s father killed himself? Of course they knew. They came to the house, tried to help, prior to the move uptown. They knew Sammy. And then, back in Chelsea, after the six-month nightmare that was Harlem, they paid Connie and his siblings special attention. They bought out Connie’s stack of newspapers nightly, tipped him heavily, gave him cold bottles of Coca-Cola from the red machine that tasted so good. Those men in suits, that AA clubhouse right there on 24th, they tried, didn’t they?

Motherfuckers at that diner, and David playing dumb. Go ahead, David, keep playing dumb, see what happens.

He decided on some light housecleaning like a nonalcoholic might. He picked up the ashtray, escorted it across the room, and was going to dump its contents out the window—but caught himself about to perform the act of an alcoholic. Your first night in the house and you want to dump your ashtray directly over the entranceway?

He laid down and prayed aloud: “Lord God Father, please hear my prayer. Bless Maureen and Artie and Stevie, grant them peace and watch over them, Father.” He called his god Father because he liked it that way. He never did have too much of an earthly father.

That man for a time up in Harlem, after Sammy and Edward passed, the man who taught Connie how to find the constellations in the sky. From that spot in St. Nicolas Park, surrounded by the night, away from the streetlamps (to let the stars shine more bright, the man said). The man’s breath on Connie’s neck, crouching behind him, the heaviness of an arm on Connie’s shoulder. The smell of talc on the man, a porkpie hat on his head. Did the man show Connie care and concern—was he really about astronomy? Holding Connie in a specific manner by the arms, directing his body to face a certain angle, to line up a constellation in the sky. The guy had his hands on me quite a bit: like that priest who taught me how to make free throws. They always position themselves behind you, these short eyes. They sure know how to pick out a fatherless kid, let me tell you. Eagle eyes for the fatherless ones. See a kid with no father coming a mile off, a short eyes can. The special talent of any moderately gifted pedophile.

I cannot picture life without it. He tried to feel out in his mind for an image of himself as a person who did not drink, and nothing came. The construct of a character named Connie Sky who lived a sober life eluded him, terrified him down to the ground, made him shudder.

An alcoholic walks into a bar.

He felt his consciousness abandoning itself, the gears of his thoughts slipping, failing to catch altogether, and his last internal ramble came as a refrain, a fervent appeal tinged by the martyrdom of his suffering.

Let me go, Connie’s heart cried, let me go, let me go.

Excerpted from the novel Cornelius Sky, by Timothy Brandoff. Used with the permission of the author and Akashic Books (akashicbooks.com).