Early Sobrieties

Michael Deagler

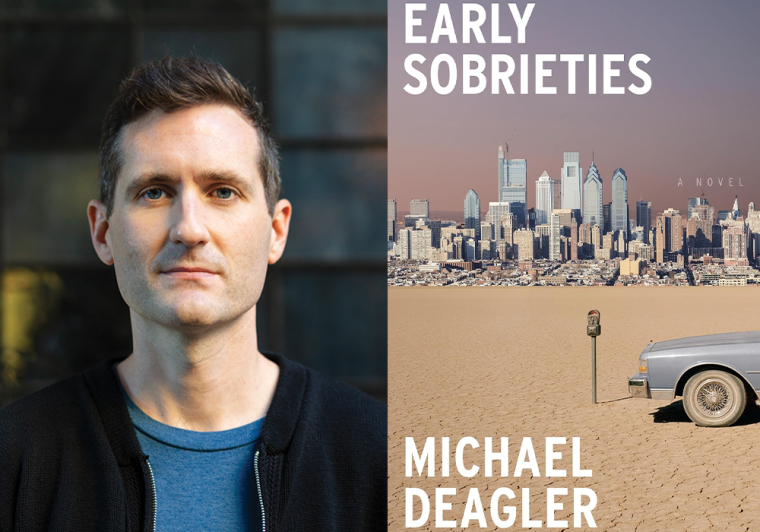

Michael Deagler, whose debut novel, Early Sobrieties, was published by Astra House in May. (Credit: Marissa Gawel)

PASSYUNK

News of my sobriety had spread throughout the land, at least among a certain subset of individuals for whom sobriety was a rare and ill-considered state. It was Oktoberfest at the Brauhaus, which, in the name of public merriment, had shut down a block of South Street in order to validate a lot of debased and antisocial behavior. Not that such conduct didn’t occur nightly on South Street, but the Brauhaus had welcomed it into the reputable light of day—to the accompaniment of Schlager and Volksmusik no less—which surely represented, if not an act of outright delinquency, at least some form of civic negligence. I came for a soft pretzel and to reaffirm my own constructive life choices.

Philadelphia was a small town when you got down to it, particularly if you sifted out those people for whom the Brauhaus Oktoberfest held little appeal. I ran into a number of acquaintances. Katie Doran was working the pretzel stand, and I imagine she mentioned my presence to Lilah Noth in the beer tent, who likely tipped off Rob Gill and his troop of inebriates, who accosted me outside the vegan café from which I was contemplating the purchase of a bubble tea. Gill had Sean Culp with him, and Sean Porth, and between the two of them they carried Mildew Hannafey like the crucified Christ, buttressing his slack, skinny arms with their shoulders. They cast the drunk man at me, repeating my name as though they believed it held incantatory properties. “Dennis Monk! Dennis Monk! Dennis Monk!”

“What?” I said. The lax face of Hannafey was pressed against my shirt. His flaccid limbs draped themselves around my neck.

“He’s overserved!” cried Gill. Gill, too, was overserved. The whole group of them was overserved. They continued to overserve themselves from the plastic beer steins germinating from their hands. “You’re sober, Dennis Monk! You need to take him home!”

“Is that Dennis Monk?” muttered Hannafey. “I know Dennis Monk.”

“I don’t know where he lives,” I said, turning my face away from the semiconscious reveler nuzzling at my sternum. He smelled strongly of beer and slightly of vomit. I knew very little about Hannafey. He was around twenty-two, on the shorter end of average height, with elfin features that suggested intoxication even when he was sober, which he rarely was. I’d only ever encountered him in low-lit bars, where the regulars evolved a sort of cave- blindness toward one another. I was alarmed to see him in daylight.

“He lives way down Passyunk!” Gill had sardine eyes, eyes terrified of ever missing a thing that happened in the world. “Down past Nineteenth!”

“I’m not going to take him there,” I said. “I don’t even have a car. Just put him on a bench for a while.”

“He’ll get sunstroke and die!” wailed Gill. “He’ll putrefy like a jack-o’-lantern!”

“Jesus, just put him in the shade,” I said, though already the old guilt was revving in my chest. I wanted nothing to do with the chemically impaired—they annoyed the fuck out of me, in a way that only those exhibiting my own inadequacies could—but for that same reason I felt an obligation toward them. They brought to mind all the people who had aided me when I had been in similar states of degeneration. All the people, too, who hadn’t bothered. Part of what impelled a person to substance abuse in the first place was the hope that, if he forfeited his faculties and lay himself before the mercy of his fellow man, some reluctant Samaritan might come along and look after him for a little while. I had once wobbled so discomfitingly before a bar in Callowhill that a woman invited me into her car and dropped me off at a friend’s place in Fairmount, asking nothing of me other than a promise that I would go straight to bed and take better care of myself in the future. Another time, a group of college students five years my junior—not one of whom I’d met before or since—bought me a late-night doughnut in Old City before sticking me in a cab bound for an address I knew in Northern Liberties. One time I stayed on the Blue Line long past my stop, all the way to Upper Darby, just to prove to a girlfriend that I was as proud as I was angry (as I was drunk, as I was baffled by my life) only to get mugged outside the 69th Street station and stumble back to her doorstep, thirty-five shameful blocks on foot, without receiving a single look of human recognition from a single person who crossed my path. For all of that—the people who’d helped and the ones who hadn’t—I agreed to get Mildew Hannafey to his bed, even though I didn’t want to. He’d become me, there in my arms, and I was someone else.

“Hooray!” cheered the inebriates, Gill and Culp and Porth and all of them, like I had solved something permanent in their lives. “Hooray for Dennis Monk!”

From Early Sobrieties by Michael Deagler. Published by Astra House. Copyright © Michael Deagler 2024. All rights reserved.