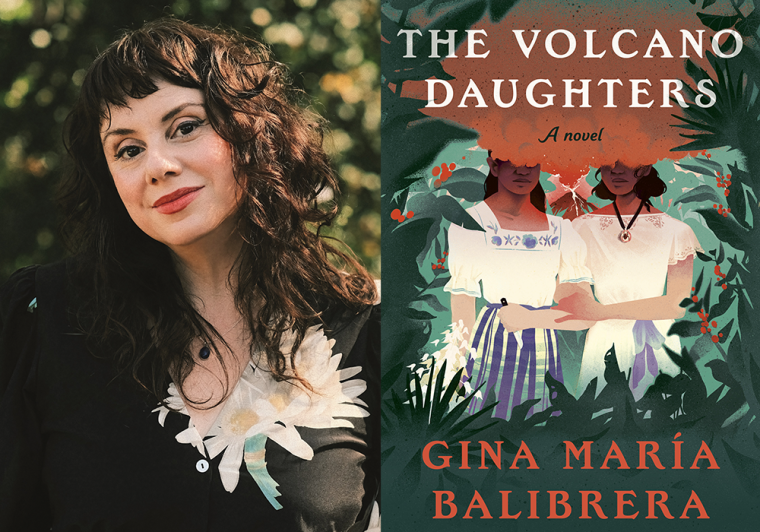

The Volcano Daughters

Gina María Balibrera

Gina María Balibrera, whose debut novel, The Volcano Daughters, was published by Pantheon in August. (Credit: Charles Amyx)

Here we are. All is still.

Cuando vos vas, yo ya vengo. We begin at la púchica root of the world.

Before we were made, the animals chattered. Jaguars spat the bones. Monkeys howled, volcanoes howled, the stars howled, cold and enormous. Someone listened and chose to destroy them, miren que, with a pair of large and ordinary hands. And after, those large hands that had made the beasts felt only emptiness. They itched to create something that could also create, beings that could carry life’s bright-blue thread through years and years, and so they rooted for just the right materials.

Poco a poco, new beings took shape. But the first, the mud creations were deemed soft and senseless; then the wood creations, bloodless and deformed. They were all cast away.

But maíz was tender, supple, fertile—talon of a wandering bird, a feather’s iridescence, a hard flake of jade, blood, milk, gold, gota a gota, formed a mano, a mano, a mano—then, slowly, we children de Cuzcatlán became too.

And us? There are four of us here in these pages. We are Lourdes, María, Cora, Lucía.

We cipotas were born of our mothers in a high, igneous sliver between the forest and the sea.

You see, before the massacre that killed us, we lived. We survived earthquakes and mudslides, the eruption of our volcano, Izalco. In the mountainside town where we all died (abandoned to rot, para más joder, piled like husks and leaves in a felled forest), our mothers had listened to radio piped in from the capital and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes in the coffee fields and never washed the black dirt from under their nails. We were in many ways like our mothers, even as we fought them, ignored them, hid from them, lied to them to run into the forest to kiss boys. (Except María—she kissed mostly girls.) What else could we do? The world was changing, everyone kept saying, but where was there for us volcano daughters to go?

Graciela was our friend. Like us, she was left for dead. But somehow she didn’t die in the massacre, as we did. Our cherita Graciela and her wannabe-chelita sister, Consuelo—when our souls discovered that they both had lived, pues, we hitched a ride on their life threads, followed along with them for the rest of their days.

Our own life threads, severed by our deaths, whip in the wind with our carcajadas. You’ve heard our carcajadas, our cackling laughter—it carries with it the stories of our mothers and grandmothers, the stories of ourselves. There are parrots in the field, and we’re always listening, siempre, a la vez. Sometimes we speak as one. Sometimes the wind scatters us apart, each a different seed. An eternal part of us remained after the massacre, the part that you hear, the voice telling you this story from all directions. We are gathering the threads of our lives, finding the words to write a new book of the people, to make our world. Miren que, the word makes the world.

Because you know what we’ve learned? Every myth, every story, has at least two versions. The growing of indigo and coffee, the movies and their magicians, the railroad tracing its long legs across our land like un pulpo, the story of a disgraced mother, a dictator, a nation’s beauties, a weeping woman beside water, a prophet. These mythic figures shift shapes, depending upon who tells their story and who listens.

From The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera. Copyright © 2024 by Gina María Balibrera. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.