Freedom of speech. Immigration status. Families separated across continents and cultures. Racial misunderstanding. Lying military officials. Corrupt political administration. These topics call to mind current headlines on travel bans and deportation forces in the United States, but they also highlight the troubles for characters in Samrat Upadhyay’s new story collection, Mad Country, published by Soho Press in April.

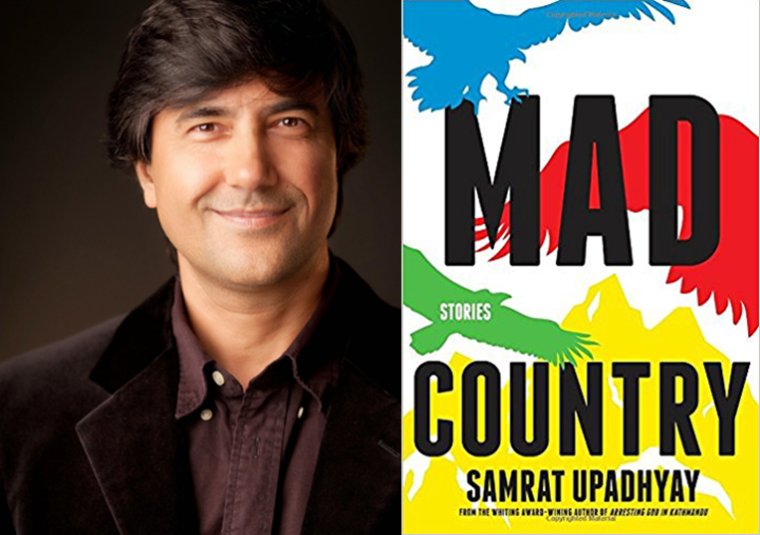

Samrat Upadhyay, author of Mad Country. (Credit: Daniel Pickett Photography)

Mad Country, described by Kirkus as “brilliant but accessible gems of short fiction,” is the latest book exploring Nepali lives, cultures, politics, and settings by the author who has been called the “Buddhist Chekhov.”

Born in Kathmandu, Upadhyay moved to the United States at the age of twenty-one. He received his BA from the College of Wooster in Ohio, his MA from Ohio University, and his PhD from the University of Hawaii. As his career unfolded, Upadhyay went from teaching creative writing at Baldwin Wallace University in Berea, Ohio, to a tenure-track position at Indiana University. His story “The Good Shopkeeper,” published in the 1998 issue of Manoa, was selected for the Best American Short Stories of 1999. Since then, he has enjoyed the kind of literary success emerging writers dream about, including a Whiting Award for his first book, the story collection Arresting God in Kathmandu (Mariner Books, 2001). His first novel, The Guru of Love (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), was a New York Times notable book. It was followed by the collection The Royal Ghosts (Mariner Books, 2006) and the novels Buddha’s Orphans (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and The City Son (Soho Press, 2014).

In Mad Country, Upadhyay widens his view to include a variety of characters, stepping beyond Nepal and the singular focus on Nepalis. The Whiting Awards website describes Mad Country as a “thrilling new collection [which] brings stories of thieves, lovers, political prisoners, fractured families, and of Nepali Americans attempting to navigate the strange customs of the United States. It reaffirms Upadhyay’s brilliant contributions to the international literature of exile.” In fact, the stories in Mad Country reflect the most sublime, masterful, and wholly original fiction of Upadhyay’s work to date.

We met this past February in Washington, D.C. to discuss his writing process, exile literature, and of course, Mad Country.

I read somewhere that you switched to writing your fiction longhand before typing it. What prompted you to do this and how does it help your writing process?

Ever since about halfway through Buddha’s Orphans, I have been writing fiction longhand. While I was writing that book, seeing my words on the screen made me feel as if it was already moving toward a finished draft, which made me anxious. I knew the novel was far from finished. So, to return to the feeling of original composition, I decided to write the novel by hand. I bought cheap notebooks and large packets of pens from Costco. It was wonderful to return to the immediacy of pen on paper. Sometimes I wrote in large handwriting; other times in small. Sometimes, I deliberately went off on a tangent and wrote stuff that didn’t seem tightly connected to the novel. The entire process loosened something up inside me, assured me that my words were not concrete, that they were malleable. It also helped when I started typing my handwritten work because I instinctually was doing minor editing as I typed. Since then, I always write my original draft by hand.

How do you start writing your stories? Is there a single method? Does each story come to you the same way?

Each story has a different origin, different trajectory. Usually I start with an image of a protagonist in some degree of conflict. There’s always a setting, a character situated somewhere, because for me the setting informs the character and vice versa. I don’t plan or map out my stories beforehand. The pleasure of discovery, of surprise, is important. I don’t want to know right away what the character is going to do, who he or she is going to meet, how the original conflict will shape the way he or she moves through the story’s landscape. So, in a way, protagonist is plot. I have very few stories that have come out of “ideas.” Or if they have, the dominance of the original ideas give way to the demands of the moment.

Do you focus on finishing and polishing one story before starting the next or do you have various stories running along at the same time?

When I first started writing seriously, I could only focus on one story at a time. I still do, but now I can work on a story and a novel at the same time. It is a relief and pleasure to work on a short story when the demands of the novel become overwhelming. After I finish the story, I’m able to return to the novel with a renewed freshness.

Do you plan to write short stories and if so how does that change your approach? How does the form guide your writing?

Almost always I know at the start of a project whether I’m writing a short story or a novel. It seems that with a short story I “know” the ending soon after I begin, even as I may not know its exact contents, so I’m already working with a heightened sense of compression and focus. It’s almost like I’m humming the short story to myself, like a small lyrical piece. With a novel, there’s a sense of settling down, going into alleys and peeking down ravines, a feeling that I’m trying to bring disparate worlds together. The long-haul aspect of the novel also makes me a more cautious writer: I want to make sure that my project is a big-idea project that’s going to sustain me for many pages and years of writing.

Has a story ever not let itself be contained in that form? What did you do?

Only once has one of my stories, upon revision, turned into a novel: my second book and first novel, The Guru of Love. And yes, it reads like a very long short story.

You once advised that writers need to plumb the depths of their characters’ souls. Good advice. How do you know when you are doing that? What do you do when you find yourself not doing that?

I think you know this when the character comes “alive” on the page, when the character is not your idea of a character but someone who has a tactile presence. You know you’re doing it when you’re allowing your character free movement in the process of writing the story, when you’re letting them surprise you by what they say and do, as opposed to what you think they should say and do. It requires an intense, raw engagement with your character.

How does one write and/or teach multicultural literature? Have you ever assigned your MFA students to write a story from the point of view of a character from a wholly different cultural, ethnic, or other background?

I do encourage my students to write from perspectives other than their own, sometimes simply as an exercise, to see how successful they can be, or what kind of research they need to conduct to do justice to that perspective. The texts I assign for my courses are invariably multicultural, international: Ishiguro, Gordimer, Rushdie, McEwan, Ha Jin, etc. I think it’s very important for American students to know of the varied literary aesthetics and concerns that exist around the world.

Do you consider yourself a postcolonial writer? A multicultural writer? How useful are labels like this?

I don’t want to be categorized. Sometimes these labels are useful so that we can create a framework that enables us to focus, but then these labels are not solid. These days I question even the identity of my “self,” whether I exist exactly the way I think I do. I am interested in a variety of human experiences, and how we articulate those experiences—and sometimes create them!—through art, so naturally my interests span cultures.

Does your wife, Babita, who is also a journalist, assist you with your process? Do you work directly with an editor on all projects?

Babita is indeed my first reader. Early in my career, I used to have her read individual stories, or portions of a novel, but I found that her critique got in the way of the kind of focus I needed to push the book toward completion. So now I give her my manuscript only after I have finished writing it. This way she can give me a more comprehensive critique. Then I send it to my agent, then on to the publisher, where I work closely with the editor to make the book ready for publication. It’s with the editor that I do much of the macro- and micro-level editorial work.

How does raising a family influence the sort of stories you write? Has it expanded your topical interests?

I have been writing about relationships for a long time, so being part of a family heightens awareness of the challenges and joys of family relationships. Experiencing my daughter’s growth into a teenager—she was just born when my first book was published and her birth energized the writing of my second book—has given me insights into the workings of young minds, so parent-child issues have also emerged in my books.

How long do you go after completing a book—mailed off, accepted for publication—before setting your sights on a new project?

I am usually well underway with my next book by the time I’ve mailed off a completed book for publication. Rarely have I had a gap, or least a big one, between books.

What do you do to fill your “creative well,” for your writing? How do you regenerate? Refresh?

I have been fortunate than my creative well has remained replenished throughout the years. But during down times I read good books, watch good movies, or simply meditate.