What’s the biggest misconception about self-publishing?

Ciotta: The stigma. Slowly, the industry is breaking away from the stigma that if a book is self-published, it’s not worthy of a publishing house, or it’s not worthy to read at all. Now that many self-published authors are businesspeople, too, their books are well written and professional and they can certainly uphold or go above and beyond readers’ standards. That being said, both traditionally published and self-published books can be amazing, good, or just plain bad. So it’s an author’s job to do his best to be in the “amazing” category and blow readers away.

What’s the future of self-publishing look like? Where are we headed with this?

Ciotta: Since self-publishing is making a ton of money, it’s only going to get hotter and hotter. We’ll see more self-published titles than ever. I believe self-published authors will bust through some major industry barriers. Perhaps the New York Times will start reviewing a self-published book once in a while, in the future. Or we’ll start seeing a few more self-published authors being interviewed on NPR or on Jon Stewart.

But most of all, self-pubbing in the future will give the power back to the readers. What the readers demand, the readers will get. And that’s the beauty of self-publishing.

Nelson: Back in 2007, my fellow agents assumed that print-on-demand was only for those who couldn’t find an agent or a “real” publisher. I never thought that. And you know why? Because over the course of my career, I haven’t been able to sell any number of projects for a variety of reasons. But I thought those novels were always worthy and ready for publication, otherwise I wouldn’t have offered representation! Now if a client wants to pursue a regular publishing deal, we go for it. But if it doesn’t happen, we aren’t necessarily despondent. We have a host of other options available to help this author find his or her audience. Traditional publishing is simply one avenue. That’s why I launched NLA Digital in 2011. It’s a platform that not only supports the reissuing of client backlist titles but also supports clients launching new frontlist titles. And, according to Bowker stats from the 2013 Digital Book World Conference, on average the hybrid author—an author who is both traditionally and self-published—will make anywhere from 10 to 20 percent more in income than authors who are just in one camp or the other. My job is to not only guide an author’s career but to also help my client make more money. Through my agent filter, hybrid looks like the future to me.

When a traditional publisher gets 100 percent behind a title and the launch is a major event, the results are unparalleled. Hands down. It’s magic, and a completely unknown author becomes a household name in less than a year. The problem is that this treatment only happens for a handful of titles in any given year. Self-publishing is the empowerment of the midlist author who would have been dropped by a publisher for sales underperformance. Now that author can find the right price point for the audience, have ultimate control, and make a decent living.

And for me, here is the last word—for now: I have yet to see a self-published title become a worldwide, juggernaut best-seller without the backing of a major publisher. Now this isn’t to say it will never happen, but as the publishing world stands right now it would be hard to achieve. Until the first one...

Nash: The future of self-publishing is the same as the future of publishing. The two are inseparable; they aren’t, in fact, even two. They are these terms of convenience becoming increasingly inconvenient, at least in terms of describing reality. Walt Whitman, Sander Hicks, Hugh Howey, E. L. James, Chicken Soup for the Soul, and Guy Kawasaki have nothing in common, except that they’re all, technically, self-published. But the reasons, the tools, the goals are all radically different. You could create an equally absurd cross section of so-called traditional publishing. Some self-publishers have agents, some don’t; some are in print, some aren’t; some do “distribution” deals (as opposed to “publishing” deals), some don’t. I know, in order to have this conversation, we have to agree for the moment to talk about self-publishing as if it existed in contradistinction to selfless-publishing, but I do hope we abandon the term quickly, so we can proceed on to helping individual writers realize their goals, matching their skills with peers and intermediaries without regard for how closely they mimic what was once called traditional publishing. We’re all publishers now. That’s both a desire and a prediction.

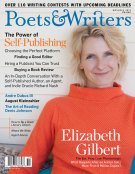

Kevin Larimer is the editor in chief of Poets & Writers, Inc.