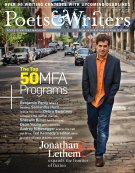

For the latest rankings of the top fifty MFA programs in creative writing, read "2011 MFA Rankings: The Top Fifty." For a ranking of low-residency programs, read "2011 MFA Rankings: The Top Ten Low-Residency Programs."

None of the data used for the rankings that follow was subjective, nor were any of the specific categories devised and employed for the rankings based on factors particular to any individual applicant.

The following is an excerpt of an article that appeared in the November/December 2009 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine. The print article, and its accompanying rankings, include eight categories of additional data for each program, including size, duration, cost of living, teaching load, and curriculum focus.

"When U.S. News & World Report last gathered original data about graduate creative writing programs, in 1996, it did so based on two erroneous assumptions. First, it presumed that no part of the writing community was better equipped to assess the relative strengths of the country's then three-score MFA programs than the faculties of the programs themselves. In fact, there was rather more evidence to suggest that no part of the community was less suited to opine on this topic than the one selected. MFA faculties are by definition composed of working writers for whom teaching is an important but often secondary pursuit; likewise, faculty members, because they are primarily focused on writing and teaching within their own programs, have no particular impetus to understand the broader landscape of graduate creative writing programs.

A second major flaw—among many smaller ones—in the USNWR approach was the premise that, unlike every other field of graduate education, graduate study in creative writing was singularly resistant to quantitative analysis, and that therefore the only category of assessment worthy of exploration was faculty opinion on individual programs' "reputations." In fact, every graduate creative writing program has (somewhere) a documented acceptance rate, an annual if changeable funding scheme, and a whole host of less weighty but equally quantifiable data points: student-to-faculty ratio, matriculating-class size, credit-distribution prerequisites, local cost of living, and so on. USNWR ignored all of these.

Irrespective of the approach taken by USNWR, the evils of educational rankings are indeed legion and do urge caution on the part of any prospective analyst of MFA programs. At base it is impossible to quantify or predict the experience any one MFA candidate will have at any one program. By and large, students find that their experiences are circumscribed by entirely unforeseeable circumstances: They befriend a fellow writer; they unexpectedly discover a mentor; they come to live in a town or city that, previously foreign, becomes as dear to them as home. No ranking ought to pretend to establish the absolute truth about program quality, and in keeping with that maxim the rankings that follow have no such pretensions. When I first began compiling data for comprehensive MFA rankings, nearly three years ago, I regularly told the many MFA applicants I corresponded with that educational rankings should only constitute a minor part of their application and matriculation decisions; that's a piece of advice I still routinely give, even as the creative writing MFA rankings I helped promulgate have become the most viewed and most utilized rankings in the field—read online by thousands of prospective MFA applicants every month.

None of the data used for the rankings that follow was subjective, nor were any of the specific categories devised and employed for the rankings based on factors particular to any individual applicant. Location, for instance, cannot be quantified—some applicants prefer warm climates, some cold; some prefer cities, some college towns; and so on—and so it forms no part of the assessment. Other factors traditionally viewed as vital to assessing MFA programs have likewise been excluded. For instance, conventional wisdom has been for many years that a program may be best assessed on the basis of its faculty. The new wisdom holds that applicants are well advised to seek out current and former students of a program to get as much anecdotal information about its faculty as possible, but, in the absence of such information, one must be careful not to confuse a writer's artistic merit with merit as a professor. In the past, too many applicants have staked years of their lives on the fact that the work of this writer or that one appealed to them more than others, only to find that the great writers are not always the great teachers, and vice versa. Likewise, mentoring relationships are difficult to form under even the best of circumstances, particularly because neither faculty member nor incoming student knows the other's personality and temperament in advance. In short, determining whose poetry and fiction and memoir publications you most enjoy yields little information about whose workshops and one-on-one meetings you will find most instructive and inspirational.

Comments

jelhai replied on Permalink

Low-residency programs

Seth Abramson wrote: "Generally speaking, low-residency programs do not offer much if any financial aid, cannot offer teaching opportunities to students,...are less likely to be gauged on the basis of their locales (as applicants only spend the briefest of periods on campus), and, because their faculties are part-time, are more likely to feature star-studded faculty rosters."

Given that hundreds, surely thousands, of people DO apply to low-residency programs each year, doesn't that suggest that many of the qualities measured in these rankings are unimportant to a significant number of students? And what is the basis for asserting that low-residency faculties are more star-studded than others? Even if it were true, how would it matter?

Finally, don't rankings merely offer a lazy short cut to school selection, perpetuating the myth that some programs are inherently better than others, when prospective students would benefit most by finding the program that is best suited to their individual aims and needs? You may not intentionally provide these rankings as a template for school selection, but you can bet that many people will foolishly use them that way, just as people use the US News & World Report rankings.

Seth Abramson replied on Permalink

Re:

Hi Jelhai,

You're absolutely right that the hundreds (not thousands; the national total is under 2,000) of aspiring poets and fiction-writers who apply to low-residency programs annually are, generally speaking, a very different demographic than those who apply to full-residency programs: they tend to be older, they are more likely to be married and/or have children, they are more likely to be professionals (i.e. have a career rather than a job), they are more likely to be (only relatively speaking) financially stable, they are more likely to have strong personal, financial, or logistical ties to their current location (hence the decision to apply to low-res programs, which require minimal travel and no moving). That's the reason this article did not contemplate low-res programs, in additional to the reasons already stated in the article. So when the article makes claims about MFA applicants, yes, it is referring to full-residency MFA applicants. Assessing low-residency programs and their applicants would be an entirely different project, requiring a different assessment rubric as well as--as the article implicitly acknowledges--a different series of first principles about applicant values.

As to the rankings that are here, keep in mind that what you're seeing is an abbreviated version. The full version, available either in the upcoming print edition or as an e-book (available for purchase on this site), includes data categories for each school: duration, size, funding scheme, cost of living, teaching load, curriculum focus (studio or academic). These are some of the most important "individual aims and needs" the hundreds and hundreds of MFA applicants I've spoken with over the past three years have referenced. Indeed, I've even done polling (the first-ever polling of its kind) to ask applicants what they value most in making their matriculation decision: in a recent poll of 325 MFA applicants (where applicants could list more than one top choice), 59% said funding was most important, 44% said reputation (e.g. ranking) was most important, 34% said location, 19% said faculty, and much smaller percentages said "curriculum" and "selectivity."

These rankings (and the article above) specifically urge applicants to make their own decisions about location, but provide ample information about funding, reputation, curriculum, and selectivity--four of applicants' top six matriculation considerations. Needless to say, many applicants will have "individual aims and needs" that they need to consider in making their matriculation decision, and I always urge them to look to those needs with the same fervor they consider (as they do) funding, reputation, location, and so on. But to imply these rankings haven't done the necessary footwork to ask applicants what their primary aims and needs are is simply incorrect. In fact, in the poll referenced above applicants were given the opportunity to vote for "none of the above"--meaning, they were invited to say that their top consideration in choosing a school was something other than the six categories referenced above. Only 1% of poll respondents chose this option. So when we speak casually of "individual aims and needs," I think we need to remember that these aims and needs are no longer as unknowable as they once were--largely due to efforts like the one that produced these rankings. And again, for those who don't see their own aims and needs reflected in the data chart that accompanies this ranking (and which you haven't seen yet), I say--as I always say--that these rankings and this data should be used only as a starting point for making an intensely personal and particularized decision.

Take care,

Seth

Seth Abramson replied on Permalink

Re:

P.S. I should say, too, that the poll I mentioned above is just one of many. Another poll (of 371 applicants, where applicants could pick more than one first choice), showed that 57% of applicants have as their top "aim" getting funded "time to write," 42% say employability (i.e. the degree itself), 36% say mentoring (which causes them to primarily consider program size, as program size helps determine student-to-faculty ratio), 34% say "community" (which again causes applicants to consider program size, though it pushes many of these applicants to consider larger programs, i.e. larger communities), 19% say "the credential" (again, as represented by the degree itself, though this also pushes such applicants to favor shorter programs, with a lower time-to-degree), and much smaller percentages said that they wanted an MFA to validate themselves as writers or to avoid full-time employment (very similar to wanting "time to write," per the above, just as "validation" is intimately related to "mentoring" and "the credential"). Again, these polls were not intended to be exhaustive, though it's noteworthy that 0% of poll respondents chose "none of the above."

clairels replied on Permalink

Suspicious

A graduate of Harvard Law School and the Iowa Writers' Workshop

I'm not accusing anyone of anything, but you have to realize how suspicious this looks.

Seth Abramson replied on Permalink

Re:

Hi Clairels,

I'd respond to your comment, but honestly I have absolutely no idea what you mean to imply or what your concern is. I attended both those programs (J.D., 2001; M.F.A. 2009), and certainly don't regret either experience.

Take care,

S.

Seth Abramson replied on Permalink

P.S. I think it was the

P.S. I think it was the reference to HLS that threw me. If you're talking about my IWW affiliation (as I now see you might be), I don't know what to tell you except to say that you won't find a single person who's well-versed in the field of creative writing who's surprised by Iowa's placement in the poll--a poll that was taken publicly and with full transparency, and whose results are echoed in/by the 2007 poll, the 2008 poll, the (ongoing) 2011 poll, USNWR's 1996 poll, and the 2007 MFA research conducted by The Atlantic. Iowa has been regarded as the top MFA program in the United States since the Roosevelt Administration (1936). In three years of running MFA polls I'll say that I think you're the first person to suggest to me (even indirectly) that Iowa might have finished first in the poll for any reason other than that it finished first in the poll (to no one's surprise). So no, I can't say that I see my affiliation with the IWW--an affiliation I share with thousands of poets (Iowa graduates 250 poets every decade) is "suspicious." --S.

sweetjane replied on Permalink

To be fair, Seth, I think

Seth_Abramson replied on Permalink

Hi SJ, Sorry for any

J Thomas Lore replied on Permalink

Acceptance Rates

J Thomas Lore replied on Permalink

And Seth, there was a link

Seth Abramson replied on Permalink

Hi JTL, Per my contract

sweetjane replied on Permalink

"Sorry for any confusion--my

Seth_Abramson replied on Permalink

Hi Phoebe, I've addressed

sstgermain replied on Permalink

question about collection of information

Seth_Abramson replied on Permalink

Hi SSTG, This was one of

ewjunc replied on Permalink

nothing is absolutley objective

sethabramson replied on Permalink

Hi ewjunc, The article's

OKevin replied on Permalink

Hi Seth, Good job. Have a

sethabramson replied on Permalink

Hi there Kevin, thanks so

illingworthl replied on Permalink

Re: UNH Core Faculty--include Mekeel McBride, please!

sashanaomi replied on Permalink

Other factors: health insurance

Since Seth Abramson is considering cost of living and funding, I think he should consider another, really huge factor: Does the school offer health insurance? There are some very highly ranked CUNY programs. Yes, CUNY is cheap, but there is no health insurance. If you really want to commit to a writing program, you don't really have time for a full-time job with health benefits. Health insurance was a big factor in my selection, and I'm sure it is for many others as well.