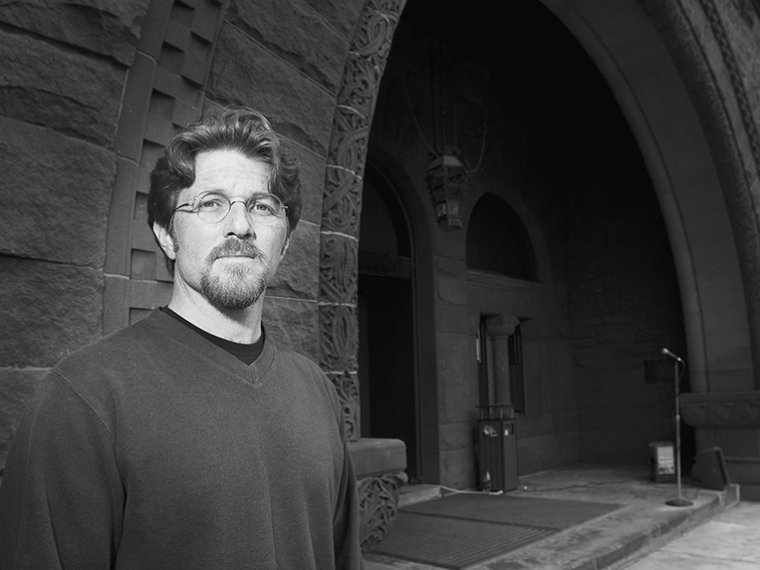

The truth is, Greg Bottoms is a liar. Just not in the conventional sense of the word. Not in the “I am not who I say I am” sense. He didn’t fabricate a million little pieces of his past in order to push a best-selling memoir. Not in the “it depends on what your definition of the word is is” sense either. You won’t find him crossing his fingers behind his back. And certainly not in the “byline: Stephen Glass” sense. What he writes is his own.

Greg Bottoms is a liar only insofar as any creative nonfiction writer is: He pursues truth through the lens of an inescapable subjectivity. For the past decade or so, he has thought carefully about how a writer uses the facts: salvaging them, preserving them, contextualizing them, personalizing them, even ignoring them. He has written about a small crowd of people’s lives—his schizophrenic brother, a suicidal writer, and outsider artists, among others—and in each instance he has tried to get beneath the surface of their stories, below the preconceived notions and societal assumptions, down to some bedrock of truth. “I think writing ought to have a kind of honesty to it, a sort of courage, but not a courage to be titillating or coarse, just a courage to keep going until you feel like you’ve gotten to the heart of the matter, which is not easy to do and can be sort of painful,” he says.

But the truth is elusive. It’s open to interpretation, as Bottoms has discovered most recently and pointedly with his new book, a memoir about outsider art and artists, published by the University of Chicago Press in the spring. In The Colorful Apocalypse, a chronicle of his journey into the lives of three artists—the late Howard Finster, William Thomas Thompson, and Norbert Kox—Bottoms explores the creative impulse, in the face of disorder, chaos, madness, and despair, to make sense of life through art. The book, which took Bottoms six years to write, is also about the fundamental act of storytelling itself and the precarious nature of writing about another person’s life.

“There’s a kind of self-consciousness in the book about the making of narrative and the making of story, which is considerably more difficult when you’re writing about real people,” Bottoms says. “Great care is required, and I think no matter how much care you take there’s some part of you that thinks, ‘Ah, did I get that right? Did I do that right? Was this even mine to say?’”

![]()

Bottoms was born in Hampton, Virginia, just as his mother and father had been, in 1970. “I come from a place where people move down the street,” he says, and indeed, his mother, grandmother, and aunt still live there, in the Tidewater region of Virginia, in the suburban New South. His father and his older brother, Michael, do not, and it is the long, dark, sometimes violent, and complicated narrative leading to their absence that is the subject of Bottoms’s first book, the memoir Angelhead (Crown, 2000), which he began writing in 1997 while pursuing his MFA in fiction at the University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville.

“My brother saw the face of God,” Bottoms writes at the beginning of Angelhead. “You never recover from a trauma like that. He was fourteen, on LSD, shouting for help in the darkness of his room in our new suburban home. I was ten.” He goes on to describe how his brother, once considered the “good-looking bad boy” of the neighborhood, slipped further and further away from reality. First there were the obsessions, with heavy metal music, martial arts, snakes—odd behavior, unsettling, but easily swept under the rug of adolescence. Then came the violence, to himself and to others, and finally—over a period of years that included a false admission of murder, two tries at suicide, and a diagnosis of acute paranoid schizophrenia—an attempt to burn down his family’s house with them still inside. Bottoms’s father, who had worked hard to establish a good life for his family in the suburbs, died of lung cancer before a judge sentenced Michael to thirty years in the psychiatric ward of a Virginia maximum-security prison.

Reviews of Angelhead appeared in the usual places—Publishers Weekly (“one of the most harrowing portraits of madness in recent memory”), Esquire, Salon, even CNN.com—but also in medical journals like Psychology Today and the British Medical Journal. It was almost universally praised for its honesty, for Bottom’s unflinching look at mental illness. But it was also a juicy story, attractive to journalists looking for a little drama, and Bottoms’s personal life—and the life of his sick brother—was suddenly open to misinterpretation. “It made me very uneasy. I felt like there’s a way that that kind of trauma memoir or confessional prose or family-chaos-mayhem-made-into-a-story goes out into the world. There’s almost a template for its reception. It started even before the publication of the book,” he says, referring to the press release that he received from Crown.

“It was almost this celebration of what seemed salable about it—‘a devastating portrait of…’—like it was this rock-and-roll book: ‘Man, this is so edgy, what an edgy story about this crazy guy.’ And I thought, ‘What? I didn’t say that. I’m saying he was my brother and it’s complicated and I loved him very much.’ All of a sudden here came this marketing-speak, and it just went out into the world. I thought, ‘Well, I’ve participated in this,’ so it made me deeply uneasy.”

Adding to Bottoms’s concern about the marketing of the memoir was his anxiety about being portrayed as some kind of trumped-up survivor. In his new book, he recounts being interviewed about Angelhead and feeling like a sellout. “I felt…that I had done nothing more than sell my tragedy in an au courant literary form, the trauma memoir, which courts, in this cultural moment, self-aggrandizement, even if that self-aggrandizement is half-buried under irony or self-deprecation.” The reason the book received the kind of reception it did, Bottoms sometimes felt, was not because of its literary merit but at least partially because it was a tragic tale.

Bottoms was still fielding interviewers’ questions about Angelhead when his next book, Sentimental, Heartbroken Rednecks (Context Books), a collection of stories set in the South that blurs the lines between autobiography, fiction, and essay, was published—just days before September 11, 2001. It did not have an auspicious start, and no one can fail to recognize at least one possible reason why, although Bottoms immediately disregards such excuses. “For me to say, ‘Gee, my book didn’t sell very well because there was a catastrophe,’ to see my own pathetic little story as mattering in all that is just ragingly narcissistic, so whatever, you write and the world goes on and sometimes people notice what you do and sometimes they don’t, and there you have it.”

A brief review in the New York Times pointed to two biographical pieces in the middle of Sentimental, Heartbroken Rednecks (which was billed by its publisher as “stories”) as lending a “hodgepodge feel to Bottoms’s book—evidence, perhaps, of a serious talent still racked by growing pains.” While the reviewer, Jonathan Miles, had a point—Bottoms himself says he disagrees with the way the book was packaged—the review glossed over the subjects of those two pieces: one about the late Southern writer Breece D’J Pancake, which was reprinted in this magazine; the other about James Hampton Jr., a janitor in Washington, D.C., whose 180-piece sculpture, “The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly,” was discovered in a rented garage after his death.

“A Seat for the Coming Savior” (later titled “Patron Saint of Thrown-Away Things: An Essay on Devotion” for a revised paperback edition of the book, published in May by Shoemaker & Hoard) was not the first time Bottoms had written about a so-called outsider artist. In the MFA program at UVA, while Bottoms was researching schizophrenia, dementia praecox, and the history of asylums and hospitals for Angelhead, he “bumped into” the topic of outsider art almost immediately and began collecting notes about three Christian visionary artists.

The first was the famous Reverend Howard Finster, an outsider artist in Pennville, Georgia, about whom Bottoms had written a short essay for the short-lived online magazine Feed. Bottoms was interested in Finster because, as a teenager in Virginia, he and his friends had seen the artist in a documentary about the mid-1980s music scene in Athens, Georgia, and something about Finster’s bigger-than-life persona struck a chord with him. The second was Greenville, South Carolina, artist William Thomas Thompson, who, in the late 1980s, after contracting a mysterious nerve disorder, traveled to Hawaii for treatment, attended a church service at which he glimpsed a vision of hell—a fire-and-brimstone, Four-Horsemen-of-the-Apocalypse type of vision—then spent three years painting a three-hundred-foot mural of the book of Revelation. And the third was Norbert Kox of New Franken, Wisconsin, once a member of the Waterloo Outlaws biker gang, who looked at his father one night and saw a vision of a crucified Jesus, wrote “nine hundred pages of Christian prophecy,” as Bottoms describes it, and began to paint “apocalyptic visual parables.”

When Bottoms heard the news that Finster had died in October 2001, he was living in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and teaching creative writing to undergraduates at Sweet Briar College—his first teaching job after graduating from UVA. He was driving through the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, listening to the radio, when he heard the report. It was raining, and as he pulled his car over to the side of the road, he decided then and there that he would go to Georgia for Finster’s memorial service—held at his four-acre Christian “visionary” art environment, Paradise Gardens—and begin what would be almost a six-year journey into the always strange and sometimes dark and contradictory world of outsider art, a journey chronicled in The Colorful Apocalypse.