Brian Castner is the author of The Long Walk (Doubleday, 2012), an Amazon Best Book of 2012 and Chautauqua Literary & Scientific Circle selection for 2013. His writing has appeared in Wired, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Outside, and on National Public Radio. Castner is the co-founder of Buffalo, Books & Beer, a new literary series in his hometown of Buffalo, New York.

We’re all still learning how to come home from a war. Veterans struggle to readjust, civilians and family wonder how to welcome back their changed loved ones. We shouldn’t be so hard on ourselves; Odysseus had trouble, too.

This truism of history still applies: Every veteran saw their own war, had their own individual experience, were exposed to their own proportion of terror and transcendence, and deal with their own mix of pride and regret. It follows, then, that no single national program or strategy will best welcome home all these men and women.

For some veterans, though, writing helps. Trauma therapy for some, but for most, just a human need to share an experience with others. The same could be said for the country at large, of course; narrative helps all of us make sense of our lives.

Inclusivity. This is what spurs Words After War, a literary nonprofit based in New York City, to organize workshops and events around the country. Rather than focusing on writing for a small circle of military peers, Words After War instead creates opportunities for veterans and civilians to speak to each other. It’s an effort to bridge the civilian-military divide, one story at a time.

This past semester, with support from Poets & Writers, I led a Words After War workshop on the campus of Canisius College in Buffalo, New York. On Tuesday evenings, war was a lens through which to read and write and think about the same topics that have always preoccupied writers. Many traditional workshops use this lens model, we simply considered violence and its aftermath instead of environmentalism or realism or faith or any other typical construct.

There is no good writing without good reading, so we started each session with Whitman or Hemingway or Vonnegut or Klay (who visited our class just weeks before he won the National Book Award). We studied classics, but also new work from Siobhan Fallon, Brian Turner, and Hassan Blasim, and two post-Vietnam books, Qais Akbar Omar’s A Fort of Nine Towers and Larry Heinemann’s Paco’s Story. What better way to start than to put great sentences—moving sentences, jarring sentences, and imperfect sentences—in everyone’s ears? An ice-breaker, for the workshopping that followed.

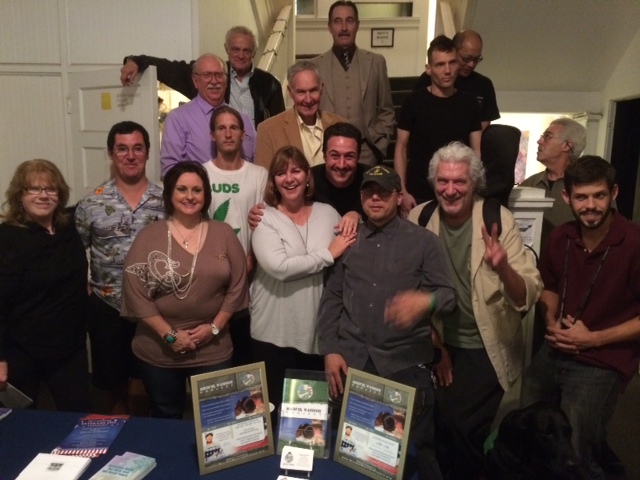

I’d like to think that the strength of our program is to be found in the stories we wrote and the precision and quality of the feedback we provided each other. To judge our success in bridging the civilian-military divide, we could parse the demographics of our group (five veterans/six civilians, four women/seven men, three graduates of creative writing programs, three retirees, a lawyer, a photographer, a poet, an anthropology professor, a magazine editor, an author of four books, one that had not written in decades), but I’d rather examine the work we produced.

Some stories you would expect from a veteran writing group—a nighttime raid in Afghanistan, a day on the gunnery range in basic training—but most may surprise. A dying grandmother who keeps a secret to the end of her life. A son with nightmares while his father fights in Iraq. Travels in Korea. A meditation in a snow-filled graveyard. We workshopped prose poems and flash fiction, chapters from novels, and a Civil War biography told through letters. Some stories had a military connection, but plenty did not; grief and love are grief and love, after all.

In short, a veteran writing workshop looks a lot like any other serious literary class. Because at the end of the day, we’re all just trying to produce good writing; Hemmingway’s one true sentence.

Photo (top): Don Bond, Brian Castner at a teaching workshop. Photo (center): Brittany Gray. Photo (bottom): Marilyn Rochester. Photo Credit: Words After War

Support for Readings & Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, A.K. Starr Charitable Trust and Friends of Poets & Writers.

Jason Frye, a travel, culinary, and culture writer from Wilmington, will serve as the final judge.

Jason Frye, a travel, culinary, and culture writer from Wilmington, will serve as the final judge.