Jane Morton

"Cowboy poet" Jane Morton reads her poem "Prairie Fire" at the Out of the Ashes: Words of Rebirth, Healing, and Hope poetry gathering in Colorado Springs on July 11, 2012.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

"Cowboy poet" Jane Morton reads her poem "Prairie Fire" at the Out of the Ashes: Words of Rebirth, Healing, and Hope poetry gathering in Colorado Springs on July 11, 2012.

The annual Troubadour International Poetry Prize, sponsored by the London-based Coffee-House Poetry and Cegin Productions, is currently open for submissions. The grand-prize winner will receive £2,500, or approximately $4,050.

The contest is open to poets from any country over the age of eighteen. Poets may submit two copies of previously unpublished poems of up to forty-five lines each, written in English, with a £5 ($8) entry fee. Submissions are accepted via postal mail only, and payments can be made by mail or through PayPal. The deadline for submissions is October 15.

A second-place prize of £500 (approximately $810) and a third-place prize of £250 (approximately $405) will also be given. Winning poems may also be published on the Troubadour International Poetry Prize website. Jane Draycott, whose latest work is a translation of the fourteenth century poem Pearl (Carcanet, 2011), and Bernard O’Donoghue, whose most recent poetry collection is Farmers Cross (Faber & Faber, 2011), which was shortlisted for the 2011 T. S. Elliot Prize, will judge the contest.

Founded in 1997 by poet Anne-Marie Fyfe, Coffee-House Poetry is a weekly reading series held at the Troubadour, a writers’ and artists’ café in London. The series hosts readings by both emerging and established poets throughout the year, and has featured poets such as Billy Collins, David Constantine, Stephen Dobyns, Mark Doty, Helen Dunmore, Jorie Graham, Jane Hirshfield, Michael Rosen, C.K. Williams, and C.D. Wright, among many others. The series also hosts book discussions, literary magazine launches, craft classes, and workshops taught by poets such as Sharon Olds, Tom Sleigh, and Matthew Sweeney. Contest submission fees are used to help support the series.

Winners of the 2012 Troubadour Prize will be notified by November 19, and will be honored at Coffee-House Poetry at the Troubadour on December 3.

For more information on Coffee-House Poetry and complete submission guidelines, visit the Troubadour Poetry Prize website.

Revisit one of your poems that needs revising, especially in terms of its length. Rewrite it on a postcard, including only what is most important, using the limited space of the postcard as your guide. When you've finished, consider mailing it to someone!

Brendan Constantine, September’s Writer in Residence, was born in 1967 and named after Irish playwright Brendan Behan. An ardent supporter of Southern California’s poetry communities, he is one of the region’s most recognized authors. He is currently poet-in-residence at the Windward School and regularly conducts workshops in hospitals, foster homes, and with the Art of Elysium. His latest collections of poetry are Birthday Girl With Possum (2011 Write Bloody Publishing) and Calamity Joe (2012 Red Hen Press). He lives in Hollywood, California, at Bela Lugosi’s last address.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with my last blog as “writer in residence” for P&W. Thanks for visiting with me today.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with my last blog as “writer in residence” for P&W. Thanks for visiting with me today.

A while ago, I came across this comment in response to an L.A. Daily News article about efforts to appoint L.A.’s first poet laureate: “The economy is in shambles, people are looking for work and the city wants to hire a poet? This is the most absurd thing I have ever heard of! I am so glad that I moved away from Los Angeles!”

Wow. How do we begin to respond to that? How does a poet help a city? Isn’t it a waste of time and resources when people are desperate? Why do we need poets at all?

Those are worthy topics. But in the days since the story appeared I’ve noticed something else. Many of the poets I know have, or have had, reservations about identifying as such. Some of them seem to have internalized the prejudice displayed in the opening quote. More about that in a moment.

First, let’s face it, the term “poet” is pretty laden (indeed, even “leaden”) with associations. Even after I’d begun to write poetry in earnest, I shrunk from using the title. It sounded like bragging, or worse, likening myself to the most extreme stereotypes of self-absorption. To call myself a poet was like telling people I made a career of being tragically misunderstood.

Yesterday I had lunch with poet Mindy Nettifee. Like all the poets mentioned in this post, she’s received grants from the Readings/Workshops program to present her work—meaning that, on some level, she’s publicly owned the title of “poet.” But when I asked her if she’d ever had reservations about it, she said, “Are you kidding? I still sometimes feel like I’ve just told people I’m a really famous mime in Texas.” I laughed out loud for five minutes.

Today I started calling poets I knew and asked the same question. I caught poet Kim Addonizio in an airport—come to think of it, I never asked where she was going, oh well—and she said that for her, the title of poet was something that had to be deserved. Writing one poem wasn’t enough. Writing two or three was still tourism. “I had to earn my stripes,” she said.

But there’s no day that stands out as the one when she knew she’d crossed a line into the territory of legitimacy. She just noticed that she had been calling herself a poet.

“It’s a ridiculous thing to call yourself,” says poet Doug Kearney. “I mean, what does it actually say about what you do? A painter’s title contains a verb. So does ‘singer’ or ‘sculptor,’ ‘dancer,’ etc…. But a poet is a...what...a poem-er?”

Kearney does identify as a poet and began to do so around the time of his fellowship with Cave Canem, a renowned writer’s conservancy with a focus on African-American authors. At some point in his residency, being daily in the company of other poets who regarded him as one of them, he passed through an initiation. But again, he noticed only in retrospect.

So what’s the big deal already? Do you call yourself a poet? There’s no shame in it, is there? No licenses to practice, no tribe with the power to vote you off an island. Do you have associations with the term (or expect others will) that give it a bad light?

Poet Julianna McCarthy, who happens to be my mom, has been writing poetry for quite some time. She has a degree and body of published work. And yet, this evening, she said over the phone, “I still can’t do it. I have to change the syntax so that instead of saying I’m a poet, I say ‘I write poetry.’”

This isn’t going to end cleanly, by the way. I don’t have any answers and I’m not blaming poets for opinions like the one appearing at the top of this post. I will say that whatever it is about poetry that inspired such passionate criticism may be related to whatever it is that stops some of us from going public.

In my first post I said: “People invent poetry as a means of expressing something they can’t easily say. The desire to talk about special things in a special way, the desire to change, elaborate, or deliberately misuse language for the purpose of greater communion is all but universal.”

I wish to add that when I say “people” I don’t necessarily mean poets. Poetry predates the job of poet. In ancient Greece and Rome, the words for poetry refer to something “made,” a thing, even a formula. In Arabic cultures it can mean to “ask” or inquire. It may also mean to “perceive.” In China and later Japan, poems are “sacred words,” “temple words.”

Who needs temple words? Everyone outside the temple. Who needs to ask or perceive? Anyone who would answer, who would face another questioner. Who needs to make a thing out of words? Anyone unmade by speechlessness.

Photo: Brendan Constantine talks with young poets at Hillsides in Pasadena, California. Credit: Nicola Wilkens-Miller

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

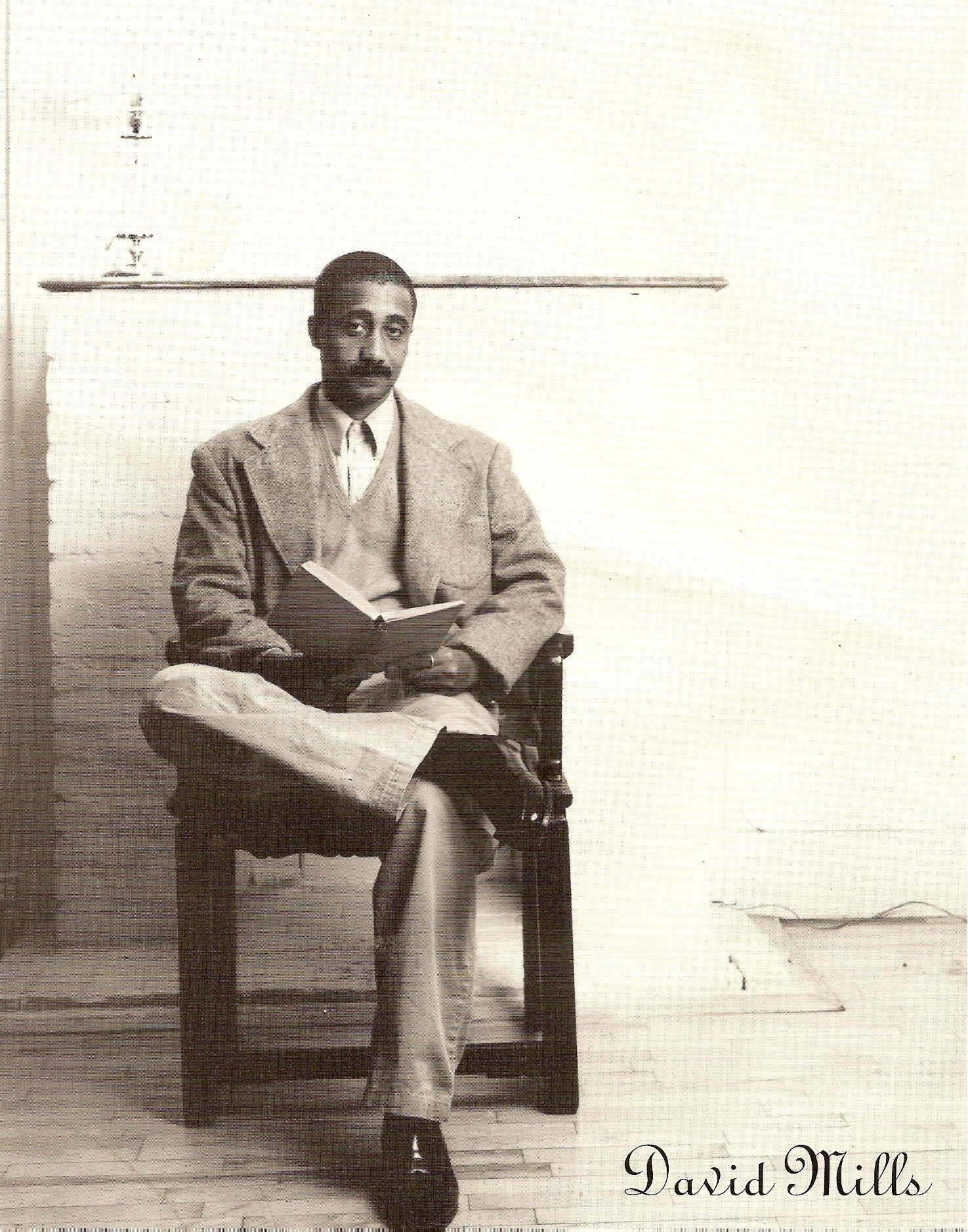

David Mills has taught several P&W–supported workshops at the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center in Chicago. He is author of the poetry collection The Dream Detective (Straw Gate Books) and has poems in the anthology Jubilation! (Peepal Tree Press) and magazines, including Ploughshares and jubilat. Mills is also the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. What is your writing critique philosophy?

What is your writing critique philosophy?

Most of the workshops I conduct are with kids, so I always write on the board “2+2=57,” which means for the hour that I am with them, I don’t want them to worry about spelling or grammar because obsessing over “crossed Ts” could mean losing a moment of genius.

How do you get shy writers to open up?

I try to present a model poem that will spark both conversation and creativity. I remind the students that poetry is not on Mount Parnassus. It’s right t/here, wherever we happen to be geographically and psychically. I make self-deprecating jokes to put them at ease and let them know everything is poetic fair game.

I sweat, so I’ll say: “I sweat while I swim. Use that. ‘How can this guy sweat while he swims?’”

I have abstract expressionist penmanship, so I’ll say: “I write like a blind man with five broken fingers. How’s that possible for a poet?”

I don’t want them to write about my idiosyncrasies, but I hope that by framing them as kooky koans the kids will access their own creative centers.

What has been your most rewarding experience as a writing teacher?

Workshops like the ones P&W sponsored at the Cook County Juvenile Detention come to mind. In one visit, I used Randall Horton’s poignant and ironic poem “Poetry Reading at Mount McGregor (Saratoga, NY).” During his own incarceration, he could never have imagined voluntarily returning to a prison, yet in the poem that’s exactly where he finds himself.

I discuss redemption.

What happens for Randall in his poem is what I hope will happen for these kids. Writing gave him a raison d’etre. Horton writes: “tonight poetry is a sinner’s prayer,” and reflects on how when he was incarcerated he “searched for the… alphabets to help me escape.” He concludes the poem: “How do I say welcome me, I am your brother?”

I got misty-eyed as I read those lines. I think the boys felt what the poem was meant to evoke: union, communion.

There were gangbangers in the class from opposing gangs—African-American and Chicano-American. The teachers had warned that certain guys had to sit on opposite sides of the room. As we discussed the poem, guys started talking across “colors,” opening up. Teachers who weren’t part of the workshop stepped in and stayed.

I asked the guys to write about returning to a place—physically or psychically--that might be filled with pain, fear, anger, or an unresolved question. I asked them to describe it physically, but to then address the wound or fear to a person who had something to do with whatever unresolved feeling was back there.

One Chicano student described a town center in Mexico where an incident had occurred that caused his family to flee to the U.S. What happened to his family is less important than what happened to his peers as a result of his avowal. His poem gave his classmates both insight into and greater empathy for him.

What do you consider to be the benefits of writing workshops for special groups (i.e. teens, elders, the disabled, veterans, prisoners)?

I have only worked with male populations where posturing and bravura run deep. But given an opportunity to see that their vulnerability will not be used against them, these boys will open up. I think some of these young men feel—and sometimes rightfully so—like the words in Patricia Smith’s poem, “CRIPtic Comment”:

If we are not shooting

at someone

then no one

can see us.

There is the sense that these boys feel both seen and heard during our time together. In one of the P&W–supported Cook County Juvenile Detention workshops, I used Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”:

I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

Hughes’s piece has an epic reach—bodies of water of mythic, cultural, and historic proportion. I talked about Hughes’s “knowing.” I got the boys to write about things they knew intimately, using Hughes’ structure to organize their “knowing.” One participant wrote about the various sneakers he has “rocked”:

I’ve known Nikes, shell-top Adidas...

You get the idea.

Another student had lived in Illinois and Indiana, so he wrote about “knowing” distinct parts of these two states, both in terms of geography but also the “temperature” of different communities.

What's the strangest question you’ve received from a student?

I am pretty zany so no question strikes me as strange. I do get a lot of “Why do you sweat so much?”

Photo: David Mills. Credit: Luig Cazzaniga.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Chicago is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Choose a poem—one of your favorites or one you select randomly—and closely analyze its structure. How many stanzas does it have? How many lines comprise each stanza? How many stressed syllables are in each line? Is there a pattern to the number of syllables per line? Once you've fully analyzed the structure, write a poem of your own using that structure.

Brendan Constantine, September’s Writer in Residence, was born in 1967 and named after Irish playwright Brendan Behan. An ardent supporter of Southern California’s poetry communities, he is one of the region’s most recognized authors. He is currently poet-in-residence at the Windward School and regularly conducts workshops in hospitals, foster homes, and with the Art of Elysium. His latest collections of poetry are Birthday Girl With Possum (2011 Write Bloody Publishing) and Calamity Joe (2012 Red Hen Press). He lives in Hollywood, California, at Bela Lugosi’s last address.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

My relationship with Poets & Writers began in 1995 when I first sought their help in paying authors to read for a local series, the Valley Contemporary Poets. In the years since, their support—both financial and creative—has enabled me to build a whole career. I’m sure you can appreciate how daunting it is, then, to try to write something “worthy.” At every keystroke I imagine someone at the P&W main office looking up from a computer and saying, “Wait, we’ve PAID this guy to give readings?”

Of course, it’s just the same old vanity that plagues every writer: the Phantom of Originality, also known as the Tenth Muse. Not only is originality a false god, history has made it plain there are no profundities so great they cannot be trivialized; death is a business, so are babies, and now Webster’s definition of “reality” includes the subheading “a genre of television.” If nothing is sacred, neither is writing.

Exactly ninety years before the date this blog will appear, a writer named Richard le Gallienne wrote a New York Times review of four new books of poetry. Before addressing any of the titles, he observes, “Unless poetry is as compelling as Ragtime, we labor in vain to read it.”

Ragtime. Join me for a deep sigh, would you?

For those of you who’ve ever felt as though your art has too much with which to compete in popular media, that it’s no match for TV, movies, or popular music, the above quote should offer some comfort. Ragtime may have topped the charts of 1922, but a good deal of transcendent writing came after, indeed most of what we call Modern poetry. Give yourself a break.

Speaking of taking a break, in Samuel Johnson’s essay “The Rambler,” he contends, “It is certain that any wild wish or vain imagination never takes such firm possession of the mind, as when it is found empty and unoccupied….” He is praising activity for its own sake, warning against the hazards of idleness. What are the hazards? Depression, melancholy, and, even worse, posthumous notoriety.

But for writers, the value of “down time,” with nothing on our minds but the cookie in our hands, is priceless. There’s no telling what combination of whim and weariness will send us into despair or creative action. But perhaps they’re the same. To be an artist is to create “stillnesses”—the stillness of the page, the plinth, and the canvas, the thousand stillnesses in one minute of film. Or dance.

To be an artist is to invite “any wild wish or vain imagination” to take firm possession of our minds, to dare boredom to do its worst, to take second place to Ragtime.

Furthermore, it will always be true that our poorest work lies ahead of us. We’re going to write something truly awful in the future. We have to. Why do we have to? It’s often the only way to uncover the good writing. Like going through a kitchen drawer, sometimes we have to take out things we don’t need in order to get at the things we do.

Ask yourself about the conditions under which you’ve done your best work so far. Did you start with a defined vision and follow it to the end without deviation? I’m guessing, No.

Where I see many of us get stuck, again and again, is in forgetting the role of “chance.” No sooner are we enjoying a sense of success (even if it’s just saying “Well, that didn’t TOTALLY suck.”) than we are forgetting the experience of discovering our art as we went.

Chances are (sorry), we’ll attempt to create something else, but this time out of sheer will. Under these conditions, we’re totally screwed. Excuse me, Ragtimed. The best we can hope for is something almost as good as we used to be.

I think the answer is to just create, create a lot, make lots of mistakes, finish a bunch of lousy work, emphasis on “finish,” but get it all the way out. Make something. Make anything. Buy a children’s paint set. Get an airplane model. Make a list of the times and conditions under which someone says “awesome” and then set it to music. Something with piano and trumpets, a trombone and snare drum. Write about a room where someone is dancing to it, someone who knows it’s stupid and dances anyway.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Read up on a famous figure (living or dead) whose personality is completely different from your own. Write a poem from that person's perspective about an important event or series of events that shaped who he or she was.

On a train from Sydney to Melbourne, four family members each wrote a short poem with the same title to create this simple yet touching video.

Created by YouTube user JankAround, this mashup of Walt Whitman’s poem “Pioneers! O Pioneers!” and footage as well as NASA animation of space exploration pays homage to the late Neil Armstrong.