W. J. Herbert

Dear Specimen

Beacon Press

(National Poetry Series)

Ghost fish, tail flapping

like a translucent scrap

of linen in the wind,

flag of surrender

with a spine inside,

eyes riding on slow

light through the deep

ocean’s darkness:

Do you know what my mother was looking for?—

—from “At the Sea Floor Exploration Exhibit, Sarah Asks”

How it began: I began drafting Dear Specimen at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, where I felt both mesmerized and saddened by the sight of a feathered dovekie tucked into a drawer, ankles delicately bound, and a tern chick floating in formalin, skin glittering. Some of the poems I wrote pointed to our brutal treatment of other species, but only a few touched on our culpability for the climate crisis. After Trump pulled us out of the Paris accord and began dismantling hard-won environmental victories, I felt despair. When I stumbled upon the Zuhl Museum in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where the fossils of five-hundred-million-year-old species are displayed beside the few whose descendants survive, the magnitude of the losses we face suddenly felt real to me. But Dear Specimen is more than a collection of fossil and specimen poems. In talking to fellow poet Tim Carrier, I realized they not only reflect my meditations on personal mortality, but also explore our connections to one another. Within six months I had expanded the manuscript to include the “Sarah” poems, intimate exchanges between a dying speaker and her daughter. Thankfully they aren’t autobiographical!

Inspiration: Wild places inspire me. In the early sixties, vast tracts of sand stretched from the foothills of Southern California’s San Jacinto Mountains to the wilderness at Joshua Tree. Eight years old and set loose to wander, I watched chuckwallas wedge between the rocks, followed the sidewinder’s zigzag tracks in the dry wash, and imagined the nocturnal lives of creatures that emerged as I lay sleeping.

As a teenager I backpacked in the High Sierra. As a parent I took our daughters on hikes led by ranger-naturalists who knew well the threats posed by climate change. Finally, on a camping trip to the Canadian Rockies in the early nineties, we drove across the Icefields Parkway at the foot of Mount Athabasca and saw for ourselves what rapid glacial retreat looks like.

Like many of us I’m fascinated by the myriad species and fragile ecological niches they inhabit: The desire to express that awe often infuses my writing. But Dear Specimen also reflects my personal landscape, and several generations of my family feel ever-present to me in these poems.

Influences: In my career as a flutist, I looked for emotional resonance in music’s complex ordering of sounds, but when our young daughters asked me to recite Mother Goose’s often archaic rhymes, I became enchanted again by language. I was writing a novel when I met Maurya Simon, author of The Wilderness: New & Selected Poems 1980–2016 (Red Hen Press, 2018). After she offered a miraculous poem to the writers’ group she had invited me to join, I switched genres. Decades later, the group still meets to share poetry, and we have become devoted colleagues and friends.

I also reached out to B. H. Fairchild, author of The Blue Buick: New and Selected Poems (Norton, 2014). Though my writing was wildly overwrought back then, he generously mentored me. I am grateful not only for his skilled guidance but for his confidence in me.

I met Robert Wrigley, author of The True Account of Myself as a Bird, forthcoming from Penguin Books, when he came to Claremont, California, to accept the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. I’m inspired by the syntactic and emotional complexity of his poems, many about the natural world. He has always been generous with his time.

I’d like to give a quick shout-out to other skilled poets I studied with: Charles Harper Webb, Joshua Mehigan, Jessica Greenbaum, and Kathleen Ossip.

Writer’s block remedy: I send myself to a writers retreat: not an actual one—mine’s imagined. Recently, the two books I took were Jacques J. Rancourt’s Brocken Spectre (Alice James Books, 2021) and Stephanie Rogers’s Fat Girl Forms (Saturnalia Books, 2021). I read both again and again to absorb their energy. Another answer to this question is: I give up on poems I’m heavily invested in, if they seem to want to be cut loose.

Advice: Sarah Kortemeier submitted Ganbatte (University of Wisconsin Press) for eight years before it won the 2019 Felix Pollak Poetry Prize, and her book is every bit as good as mine. Keep submitting!

To those who write and intend to publish a book, I’d say: Avoid idolizing anyone. On your particular journey, only you can see how dark the water, how luminous the light.

Finding time to write: As a flutist, I encouraged students to practice: Whether for five minutes or five hours, the first step is opening the flute case or picking up the pencil. Before I had a smartphone, I scribbled on a notepad that I kept in my back pocket. I rarely miss a day, but everyone knows that writing practices differ wildly.

Putting the book together: During a weekend chapbook workshop given by Arisa White through the Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance, I learned to think of each poem as energized by earth, air, fire, or water—amorphous categorizations maybe, but a way of understanding the visceral effect of each on the reader. Too many fiery poems in succession and they’re scorched. Too much water, they drown. Ordering in this way helped me to sense the resonance between poems. The process also helped me to create two parallel journeys for the larger manuscript: one, the inexorable arc of a single human life as it’s lost; the second, a slow unfolding of geologic time juxtaposed with the immediate and horrific extinction event we’re experiencing.

What’s next: I’m writing kaleidoscopic poems exploring the moment of my mother’s death. But I will also make calls and/or knock on doors in advance of the 2022 midterm elections. I’ve joined Bill McKibben’s new climate activist organization, Third Act, and will continue to participate in the Sierra Club’s climate campaigns.

Age: The calendar says I’m seventy, but that can’t be right!

Residence: In Portland, Maine, most of the time.

Job: I’m a retired performing and teaching flutist.

Time spent writing the book: Rick Bass once said that as he was learning he wrote one hundred stories, or the same story one hundred times. So for me, three years. Or three decades. Both are correct.

Time spent finding a home for it: I sent a version without the “Sarah” poems to the 2019 National Poetry Series, as well as to a few other contests that year. I wrote the collection’s “Sarah” poems over the next six months, then resubmitted it to the 2020 contest. Because Dear Specimen was my first manuscript, I was delighted when Kwame Dawes selected it for the National Poetry Series.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Meghan Dunn’s Curriculum (Gunpowder Press), Jenny Qi’s Focal Point (Steel Toe Books), Susan Nguyen’s Dear Diaspora (University of Nebraska Press), Trevor Ketner’s [WHITE] (University of Georgia Press), Amanda Moore’s Requeening (Ecco), and Devon Walker-Figueroa’s Philomath (Milkweed Editions).

Dear Specimen by W. J. Herbert

![]()

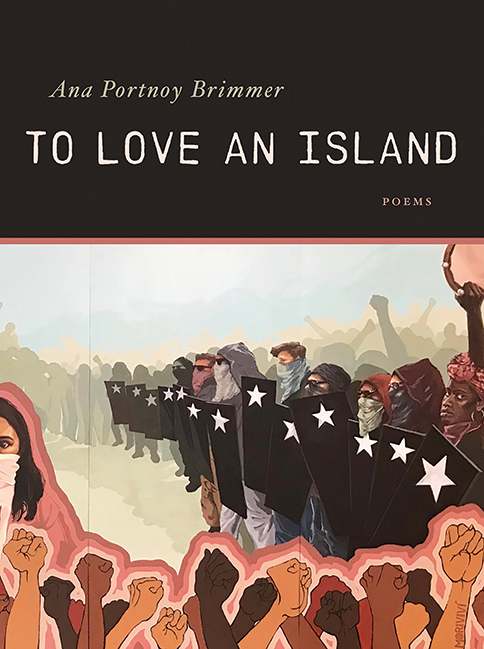

Ana Portnoy Brimmer

To Love an Island

YesYes Books

If the intimate conceivement

of self is to call upon a history

of place, summon the spirit

of home. If when I write

a poem, every poem I write

is home. If when I write

this poem, I ask you to forgive me

for the earth tumbling out of my mouth.

—from “Forgive me when I speak of land”

How it began: If I’m being honest, I wish this book never came to exist. By this I mean I wish the conditions and circumstances that brought this book to fruition—hurricanes, earthquakes, political disasters, colonialism and all the ongoing violences that come with it—never afflicted the place I call home, but history stretches too far back into those storms. Right after Hurricane María made landfall in Puerto Rico—when most of the population, if not all, was stripped of electricity, water, telecommunications; so many, of their lives—I sat under a propane lantern in the dark of my parents’ house in Mayagüez and started writing because for a while there was nothing else I felt I could do. I joined mutual aid efforts and grassroots brigades, reciprocated caretaking with neighbors and loved ones, but the systemic abandonment and forced isolation that followed in the aftermath of María for Puerto Rico was scarring, to say the least. Writing poems about what I was experiencing and witnessing was one of the ways I survived this phenomenon that marked an entire generation of people. And unbeknownst to me, that’s how and when To Love an Island started and continued to take shape as Puerto Rico’s crises unfolded along with my own political formation. The book and my relationship to it have had many iterations throughout the years. More than anything, I hope that this book, as part of a larger tapestry of poetic and political traditions, inches us a little closer toward collective mourning, healing, and the sovereign futures we ardently fight for.

Inspiration: Definitely poets, writers, and at times singer-songwriters working under decolonial and revolutionary traditions, for the unbridled and exquisite ways they reconcile politics and sentimentality. Contemporary poets I’ve built relationships with—such as Raquel Salas Rivera, Nicole Cecilia Delgado, Lark Omura, Laura Villareal, Richard Georges—who have crafted such a careful and lush poetics around home, landscape, and the intimate. Caribbean theory and landscape. My MFA and workshop cohorts have been spaces of meaningful exchange. My family, for encouraging leave-takings, returns, and creative pursuits. And of course, compas and comrades, and the legacy of those who came before us, for the expansiveness of their imagination.

Influences: This question always feels limiting and the responses incomplete, but this book lives and breathes thanks to community that accompanies and precedes me. Raquel Salas Rivera for their decolonial imaginary. Nicole Cecilia Delgado’s Periodo Especial (Aguadulce/La Impresora, 2019) and Kei Miller’s There Is an Anger That Moves (Carcanet Press, 2007) for teaching me how to write my way (back) home. Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler (Coffee House Press, 2008) for engaging the politics of disaster with such grace and inventiveness. Rigoberto González, Willie Perdomo, Dannabang Kuwabong, and Loretta Collins Klobah for guiding me in the delicate dance of developing voice.

Writer’s block remedy: I’ve slowly been learning that an impasse is more often than not a warning sign you don’t want to miss, and burnout the result of disregarding it. Capitalism wants your writing practice to be a self-flagellating experience. I’m gradually training myself to listen to these moments and embrace them as signs to feed other areas in my life that may be lacking, or simply give myself the detour and rest tugging at me. I’ll sometimes go for walks or runs; blast music and dance (I love dancing); spend time with friends, community, family, and loved ones; organize, jam, and get creative with comrades; take myself on dates; spend time with the stray animals that hang out at my parents house; watch a silly movie; cook and eat food that I relish; rest; and get into the practice of reminding myself that an impasse is sometimes nothing more than life asking you to move in a different direction for a while.

Advice: Here goes my humble and ever-evolving advice: (1) Writing is a collective experience; you’re never writing alone. Your work is woven through with all the people who have moved you—whether that be other writers, visual artists, musicians, your teachers, your comrades, your neighbor, your mother, a stranger. Writing may often be a solitary practice, but it never happens in a vacuum. Take the time to reflect on and pay homage to the people, traditions, and lineages you’re writing under. (2) Don’t mine your trauma. Establish healthy boundaries with your craft. There are already so many external forces trying to exploit you and your hurt—don’t be one of them. (3) Like any living creature, you have to feed your poetry. To do so, remember to go out into community, explore yourself outside of poetry, do things and meet people and contribute to the continuous task of world-building. And avoid basing the whole of your identity on being a writer. You are valuable and worthy outside of your craft. (4) Read internationally; develop a broad geopolitical reading practice. (5) Hold on tight to your values and politics as your book makes its debut; how the book moves through the world is just as important as what’s in it. (6) Writing won’t always come to you, and that’s okay. There’s so much left to do in this world. Come—join la lucha!

Finding time to write: These days, navigating a global pandemic, the ongoing political disasters we’re subject to in Puerto Rico and worldwide, and my mental health, it’s been hard to both carve out time to write and find the impetus to do so. After finishing the MFA program at Rutgers University-Newark and moving back to Puerto Rico, I also had to rethink my writing routine. At the moment, I’m exchanging poems with a dear friend and poet, Laura Villareal. We send each other a poem a month, usually at the end of the month, but it varies. Some months we’re able to send each other work, others we aren’t, but it’s a consistent and gentle deadline that we can count on. And it’s always such a joy to exchange poems and watch our work grow and evolve.

Putting the book together: I attended the MFA program in creative writing at Rutgers University–Newark, which is where To Love an Island was completed. I had the privilege of having access to a gorgeous wooden, winding table I could spread my poems on. Once the pandemic hit, I kept organizing my manuscript on the floor of my apartment. There were poem clusters all over the floor arranged in different shapes and orders. I remember sending my parents pictures of the spectacle. Friends and mentors at my MFA program suggested using colorful sticky notes and markers to help conceptualize and organize clusters more efficiently. Ultimately, putting the manuscript together was a combination of accounting for the chronological, thematic, and conceptual—which led me to divide the book up into different sections—and trusting in the experiences that birthed the poems in the first place.

What’s next: I’m currently working on my second poetry collection. I’m attempting to explore the intersections between sex(uality), disaster, political organizing, and a return home to Puerto Rico. When I started the project, I was reading Bhanu Kapil’s The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers (Kelsey Street Press, 2001) and Hala Alyan’s The Twenty-Ninth Year (Mariner Books, 2019), both of which were influential in framing and conceptualizing the book. While some of the poems consider the vulnerability of exploring sex and queerness in tandem with pandemic isolation and trauma, others contemplate the ongoing violences of a colonial state and imperial overseer, the hope for a decolonial and anarchic future, all the while holding the amassed grief from which Puerto Rico has found no respite. I’m also organizing and doing beautiful and meaningful political work with the Alacena Feminista-Luquillo, which feeds my poetry in so many ways.

Age: 26.

Residence: I live on the northeastern coast of Puerto Rico, in the town of Luquillo.

Job: I’m currently working as an education and outreach specialist with the Puerto Rican Literature Project, and I’m on hiatus from working as the impact producer for the documentary Landfall by director Cecilia Aldarondo, along with the comings and goings of other freelance side gigs.

Time spent writing the book: I started writing these poems days after Hurricane María devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017. Since then, I wrote and revised poems alongside Puerto Rico’s ongoing political disasters until about mid-2020, so approximately three years.

Time spent finding a home for it: When I started submitting To Love an Island, it was in chapbook form, and it took about a year and a half to get picked up. YesYes Books gave it a home as the winner of the 2019 Vinyl 45 Chapbook Contest and then offered to publish an expanded edition of it as a full-length collection, along with a Spanish edition of the book in collaboration with La Impresora in Puerto Rico. I worked on both editions during my time in the MFA program at Rutgers University–Newark, and prior to that as a master’s student in the department of English at the University of Puerto Rico.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: To be honest, I have been reaching farther back in my reading, whether by a few years or decades, and have not kept up with this or the last year’s debuts. A few of the books I’ve been reading recently are The Rebel’s Silhouette: Selected Poems (University of Massachusetts Press, 1991) by Faiz Ahmed Faiz and translated by Agha Shahid Ali; The Veiled Suite: The Collected Poems (Norton, 2009) by Agha Shahid Ali; I Don’t Want This Poem to End (Interlink Books, 2017) by Mahmoud Darwish and translated by Mohammad Shaheen; We Are the Ocean: Selected Works (University of Hawai’i Press, 2008) by Epeli Hau’ofa; The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers (Kelsey Street Press, 2001) by Bhanu Kapil; The Twenty-Ninth Year (Mariner Books, 2019) by Hala Alyan; Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting (Peepal Tree Press, 2017) by Shivanee Ramlochan; Periodo Especial (Aguadulce/La Impresora, 2019) by Nicole Cecilia Delgado; La distancia es un lugar (La Impresora, 2020) by Amanda Hernández; 4645 (Editora Educación Emergente, 2020) by Christopher Powers Guimond; and Sobre el hombre y otros sistemas de colapso (La Impresora, 2020) by Karla Cristina.