Moheb Soliman

HOMES

Coffee House Press

Concrete rubble to Lake Ontario / wear me down to my girders / the lake / the half-naked lake / slipping off its jersey / started in with its cats’ tongue

—“From jots at probably Tommy Thompson Park, Toronto when this all started”

How it began: This book is an accumulation of poems often started on site and/or en route as I lived and traveled for years all around the Great Lakes, nurturing a growing fascination with, and finding much fodder for, the overlaps of nature and modernity there and in the sprawling Midwest. As I was also trying to settle in Canada after much U.S. transience, I became preoccupied with the tangle of belonging and identity and place. The poems started as renderings, dispatches, scraps, and jots, and in between projects and travel in the region, developed as memories, conjurings, pangs, and plans. As I kept setting off, inhabiting and understanding this region that’s been at the edge of my consciousness and so far out the back door, the capturing and interpreting was happening for me as a matter of course.

Inspiration: The countless diverse places along the shoreline: towns, cities, hamlets, reservations; national, state, and other managed wilderness; the in-between wild spaces; industry and ghost towns; individuals, families, and communities I was outside and inside of; all that I saw and returned to and made much of.

Influences: Walt Whitman was foundational to me, and I’ve kept finding him, differently. His place as a supreme nature poet who also celebrated metropolises and people and this country, and his ability to write ecstatically, all was enthralling.

Sekou Sundiata was a teacher of mine; his spoken-word work totally captivated me in transcending the form and living just as much in jazz and performance art rooted in poetry.

W. G. Sebald means so much to me—spellbinding in excavating and interpolating place and history and consciousness through physical and psychical inhabitation and experience.

Adrienne Rich. She gives me the chills—her prowess and passion with the personal-political intersection and her lyricism and style and forms really give so much to sink into and take away.

Can’t even go into other artists! So much music truly constitutes my writing practice in ways I probably rightfully couldn’t put into words.

Writer’s block remedy: Honestly, simply: not thinking of writing as anything more than the excess of rich, lived life. Casting writing and art aside and letting them come crawling back and find me outside or doing something else that’s so differently, existentially gratifying. But for a long time now I feel like I’ve barely had much time like that—I’m bad with work-life balance and efficient productivity. And there’s a lot of anxiety in struggling. It’s necessary to put some discipline and perspective into those moments instead of simply walking away to take a dip or day trip or stress-eat pretzels.

Advice: Well, two maybe contradictory points. (1) Write with abandon! Forget publishing it, and just write the thing as your heart desires; that’ll hopefully circle back to having a better, realer book to put out. (2) Don’t write it forever! It’ll change and develop—the editing process was long and deep, in my experience, after getting the book picked up, so just get the manuscript to a complete-enough, solid place to share.

Finding time to write: For me, it’s never happening and always happening. This could mean both that there isn’t enough discipline and routine in my life for writing, and also that I’m doing good writing all over the place, literally, and at strange times between (and during) things (when I shouldn’t be) and that’s making the writing actually better, not in a vacuum but in relationship to lived life.

Putting the book together: This book is in part based on circumnavigating the Great Lakes (the five lakes are in fact one connected body of water) and a close engagement with the many diverse places and spaces along the coastline, and the poem titles reflect that. The book could have been organized spatially, following the coast in order of places encountered, or organized by lake, all to emphasize a journey and the geography. Or it could have buried all that under a more thematic or other content-based organization. But I always had a conceptual geographical framework in mind from what vividly had always captivated me: That this region, ecologically/historically/more, is “one place.” So I wanted to work that into the very structure of the book, crisscrossing the Lakes with each poem, putting far-flung yet similar interstate and international places next to each other, not allowing the geopolitical divisions to run the book, overlaying the natural and cultural as it really is especially in this region. Even the titles question the definitions of place in mixing the regulated proper nouns with the more ambiguous marginal nomenclature for spaces.

What’s next: I’m wringing my hands over a different book of poems about American wilderness and identity from the perspective of Hi Jolly (Hadji Ali), an obscure figure in U.S. history brought from abroad by the military in the mid-1800s to work in their experimental, failed “Camel Corps” as an animal handler and driver. Also, loathing to write a more creative nonfiction book dealing with the black hole of cisgender masculine identity/body crisis that I’d like to call The Man With Beasts, about gynecomastia. Kind of a micro-nature book, in contrast to this macro one, HOMES.

Age: 42.

Residence: Minneapolis.

Job: I’m a cobbler; I cobble together grants, arts administration jobs, and interdisciplinary projects. This past year for a living I’ve been part of the Tulsa Artist Fellowship program while also working a gig for the City of Minneapolis as a public art manager and completing varied small grant projects and art commissions.

Time spent writing the book: Short answer: over a decade.

Time spent finding a home for it: For a very long time I didn’t try at all to find a publisher; I didn’t think I was literary enough. Then I moved to Minneapolis, home of three of the top, most amazing indie presses, and I was working for the Arab American lit journal Mizna, and things just came together and I was actually solicited for the manuscript. However, it took two years to get officially accepted, and another couple to get put out. Bands rise, break, and reunite in the same time frame of this book. Such is literature?

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: I must shame myself in an effort to change: I’m a terrible reader, like a real food-finicky baby. Anyway, one beautiful one to mention that comes to me: Michael Kleber-Diggs’s Worldly Things (Milkweed Editions).

HOMES by Moheb Soliman

![]()

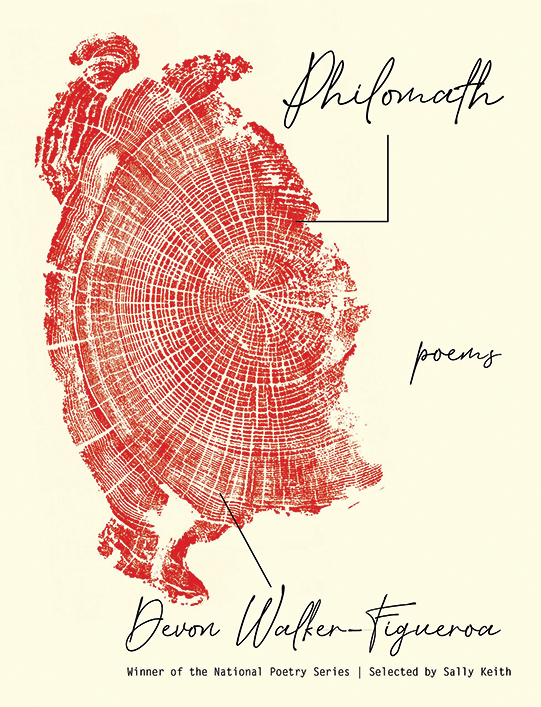

Devon Walker-Figueroa

Philomath

Milkweed Editions

(National Poetry Series)

The neighbor is eating locusts again,

as if a plague were just another

point of view, sitting out back of his caved

two-story, squinting skyward, a cast

iron in hand, a mouthful of

wings ground to dust.

—from “Kings Valley”

How it began: A place, a people, a state of mind, a set of experiences that haunted me.

Another way to say it: I never set out to write a book called Philomath. The first lines of what would become the book took shape in a candlelit basement in Salem, Oregon, where I was bartending at the time. I’d scribble lines of poetry on guest checks and either stuff them in my apron or under the register drawer until my shift ended.

What would become the title poem of the book came along a couple of years later in response to an undergraduate poetry assignment given by Michael Dumanis at Bennington College. Michael had lit a fire under my heels and given me a new sense of the poetic line by introducing me to poets such as Shane McCrae, Samuel Amadon, Olena Kalytiak Davis, C. D. Wright, Kiki Petrosino, and Lucie Brock-Broido. With their voices fresh in my ears, I set out to write a poem that captured something of the essence of a world I’d passed through, or which had passed through me and left significant traces of itself. I called “Philomath” my “hometown poem.” And I’d go back and write more poems in this mode during my grad years at Iowa and a couple of years beyond.

The rest was just longing—to hold on to and preserve what’s receding from my consciousness; to connect with others in ways I can’t seem to when I’m physically in their presence; to estrange myself from what I “know”—and regret, which is also just a form of longing, I suppose, for the past to be other than it is.

Inspiration: A single-wide mobile home decorated with painted saw blades. Russian ballet teachers and Oregonian loggers. Harpists and cowboys and Gloucester’s leap. Vacation Bible School. Microwave dinners and ghost hunters. Lorenzo Ghiberti’s bronze reliefs on the Baptistery doors in Florence. An illuminated tank at the Oregon Coast Aquarium that’s full of moon jellyfish in their medusa phase. Loitering in art museums and used bookstores. A Season in Hell and The Divine Comedy. György Ligeti’s Atmosphères. Also, the voices of so many different people. I was a bartender for a number of years, so I got to hear a lot of tongues wag—that was a gift. Such blues and gossip and intoxicated babble. Those voices, their stories and syntactical tics and slang, they stick in my head until I metabolize them and then they find some phantom presence in a poem, the way everything we eat, in its way, becomes a tiny part of us, a bit of ATP flitting through the bloodstream, though we don’t see it happen. Which is to say, inspiration might be inevitable and often occurs when we aren’t looking or don’t yet feel it animating us.

Influences: Jorie Graham’s poetry found me at a crucial moment in my life, and my admiration of her swift and breathless movement and fearless images, which also often double as portals through time and space, has never faltered. The hypnotic abundance and onrushing music of Nathaniel Mackey’s “Mu” and “Song of the Andoumboulou” poems helped me to stop imposing so many arbitrary limits on my poems and enabled me to listen more closely to the poem as it was taking shape, to sense where the lines, and not just I, wanted to go. Lucie Brock-Broido’s daring and polytonal sense of line, intimacy of address, and elastic diction that reaches back in time and deep into the present moment all at once, was life-changing for me as well. The ballet and modern dancer Sylvie Guillem has greatly influenced my work, too, not just in terms of what I strove for in ballet, when that was my profession, but how I now approach sculpting the human form and moving through language on a page. Her versatility is astonishing, her ability to shift seamlessly from machine-centric to animal-centric movement styles and to evoke the ethereal and the earthen in a single step, not to mention her balance, surreal flexibility, and breathtaking lines—all of which continue to enrapture me and shape how I move through and with art.

Writer’s block remedy: I’m a big fan of denial when it comes to “writer’s block” or “burnout.” I like mostly to pretend it’s a made-up thing. But for the moments when my head is overcrowded with data to the point of being numb or I just can’t convince myself with my flat-earther approach to burnout, for the moments when I feel so far from the words as to be exiled from them, I try a two-pronged approach of returning to my roots—that is, the poetry I read that first led me to respond to it by writing poetry—and then simultaneously reaching far from my own sensibilities and seeking out works that challenge any aesthetic I might have settled into. The idea being this: Find the roots in order to move the roots, to transplant your writer’s mind, as it were, so you can draw from the strength you already have but also draw in new nutrients from soil you haven’t leached out with endless searching and absorbing and reabsorbing. To me, it’s all about the reading—whether what you’re reading is the page in front of you or the room in which you sit.

Advice: Don’t stop or pause your writing just because you’re trying to focus on getting your first book out there. The continuation and development of your creative process need not be disrupted by the apparent completion of a single work. Also, be selective but also take some risks when you send out. And by that I mean get to know the presses to which you are submitting. Know the styles they gravitate toward and make educated decisions about whether or not your work fits with their larger project. Also, if you think your work would meaningfully complicate what a given press is up to, that might be a good reason to submit there. Because the truth is that editors get tired of writers just sending them material that “fits” with their, the editor’s, past selection habits. Everyone wants the chance to change, even editors. Point being: Send to the place where your work fits, sure, but also consider sending to some places where you think your work would meaningfully expand their scope or complicate their catalogue in some way.

Finding time to write: It’s all about finding time to read for me. If I’m reading deeply, then the writing follows of its own accord. Reading is an incredibly creative act, as much so as writing. It just doesn’t always have a physical artifact to prove itself to the public. When it does, we call that criticism, I suppose. I also find time by being flexible when it comes to environment. Basically, I think one can write anywhere if the music or image or sense or mood driving the poem-to-be strikes them. I once drafted a sestina on my phone while commuting on the PATH train—with a woman dressed up as the Corpse Bride practically sitting on my lap as I did so. It was incredibly loud, but I didn’t register that once I got my head into those lines. Obviously, a lot of time and quiet are preferable, but that’s just not always possible, especially for people who don’t get summers off or have punishing work schedules/commutes. And sometimes an external source of chaos can actually be the thing to jar you into the act of writing. You never know.

Putting the book together: I ordered the manuscript in every way I possibly could until I found a mixture of methods that worked—namely identifying modes and intermingling them, keeping a certain proportion and space between them, then finding a sort of end-to-beginning relation (think crown of sonnets, but not quite), and, finally, using something my mentor, Jane Mead, called “bookending,” which is to pick what you want to be the first and last poem of the book and then the first and last poems within any given sections. Her suggestion was to work inward from there. I found that helpful. Also, I had a number of people read and give me feedback on ordering, which helped clear some of the noise. You can look at your own work for too long, until the visual analog to semantic satiation occurs and you think, What on earth am I even looking at here? That’s when it’s time to call in your trusted readers, and you don’t need many. I think I had just three.

What’s next: I’m working on a collection of interwoven novellas-in-verse and finalizing edits on a collection of poems in form, but forms whose DNA I’ve re-sequenced, so to speak. On the prose side, I’ve been writing a novel built around the theme of hunger, though it’s too inchoate to talk much about. (To utter its working title would be to blow it to the ground!) I’m also working on translating the poems of my great grandfather Francisco Figueroa into English. His poetry is known in Guatemala and Honduras, but not so much in the so-called English-speaking world. I would like to change that, if I can.

Age: 34.

Residence: Brooklyn, New York.

Job: I teach undergraduate creative writing at NYU, where I’m completing my second MFA, this one in fiction. I’d like to keep teaching and/or return to literary editing after I graduate in the spring.

Time spent writing the book: I wrote the first poem in 2014 and the last poem in 2020, so it took six years to complete, though I wrote a second collection concurrently. I needed that—the sort of alternating current that comes from moving back and forth between two projects.

Time spent finding a home for it: The manuscript under this title and in this form took one year to place. But if you count earlier versions, it took two and a half years.

Recommendations for debut collections from this year: It’s hard to pick just a few. Laura Kolbe’s Little Pharma (University of Pittsburgh Press). Desiree C. Bailey’s What Noise Against the Cane (Yale University Press). Emily Pittinos’s The Last Unkillable Thing (University of Iowa Press). Steven Kleinman’s Life Cycle of a Bear (Anhinga Press). W. J. Herbert’s Dear Specimen (Beacon Press). Michael Kleber-Diggs’s Worldly Things (Milkweed Editions). Threa Almontaser’s The Wild Fox of Yemen (Graywolf Press). Benjamin Gucciardi’s West Portal (University of Utah Press). Catherine Pond’s Fieldglass (Southern Illinois University Press). Natasha Rao’s Latitudes (American Poetry Review).

Philomath by Devon Walker-Figueroa

Dana Isokawa is a writer and editor living in New York City. She is the managing editor of the Margins, the literary magazine of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and a former senior editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.