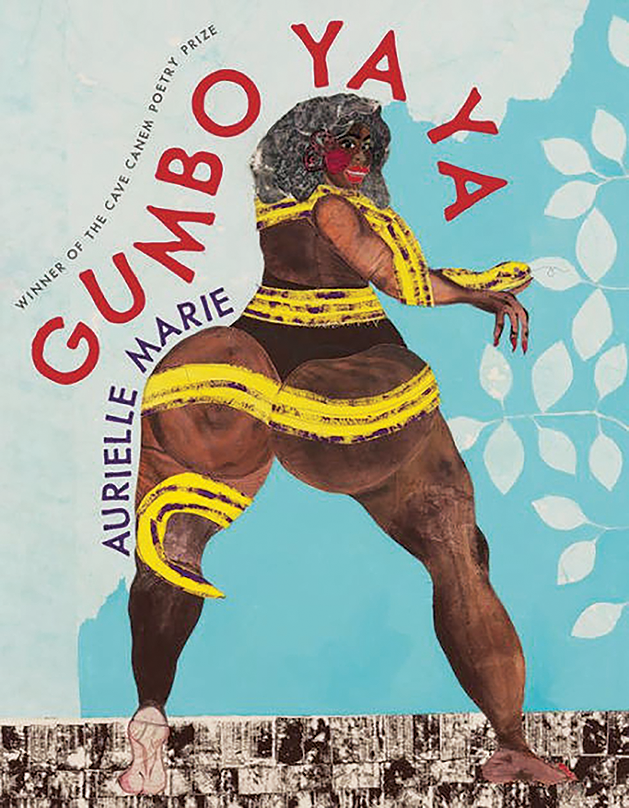

Aurielle Marie

Gumbo Ya Ya

University of Pittsburgh Press

(Cave Canem Prize)

the opposite of flying is

death the opposite

of falling is death

the opposite of death

is a skinned knee and only a skinned knee

—from “gumbo ya ya”

How it began: In the early stages of Gumbo Ya Ya, I was a community organizer who had been kidnapped by the police, trying to figure out what I wanted in life. That traumatic experience, being unable to write about little dissonances between who I imagined myself to be as an organizer and who I was as a writer. So I began the project to suture these two selves together. I don’t think I ever set out to write a book; I was simply trying to soothe these jarring dissonances interrupting my life: police and fathers, pleasure in the midst of what felt like a (race) war. What emerged was a road map or a monument, carved out of the “both/and.” This book is tender math, a slow testament to the discordances that are alive at the intersections of our identities.

Inspiration: In A Map to the Door of No Return (Doubleday Canada, 2001), Dionne Brand writes, “Having no name to call on [is] having no past....” And that has always felt true, even before I heard the phrase. In trying to more deeply understand and articulate what Gumbo Ya Ya was trying to do/is doing, I had to build identities from fragments—my mother’s great-grandfather’s surname, the recipe for gumbo from a great-aunt, the resting place of our oldest matriarch’s bones—and believe in spirit, in conjuring, and in my egun enough to trust that the past was reaching itself out to me. Mapping backward created opportunities for me to talk to all my family in new ways, both ancestors and alive kin in tandem. It’s been the biggest gift.

Influences: Noname is a hip-hop artist who is, I believe, one of the great revolutionaries of our time. Not that I believe her praxis is perfect, but I believe she is committed to using her art and her work to further ideas of liberation and create access for marginalized folks to have rich discussions among ourselves. I want to be creating in a way that does that tricky, tricky work as well. I read Dionne Brand and Saidiya Hartman and meet myself on the page. From them I’ve learned not just the criticality of storytelling but the value of fugitivity and audacity on the page. Also, my friend and peer Da’Shaun L. Harrison, an essayist and theorist, has helped keep me accountable on the page to the things I believe and profess off of it. And to trust that my work is rigorous enough, scholarly enough, doing theoretical and practical labor.

Writer’s block remedy: If the impasse is merely an impasse, I grab a writing prompt from the workshops I took with the genius Franny Choi. Her prompts always encourage me to lean into the strange, the wild, the fugitive, and I get to work. Mama ain’t raise no quitter.

But usually real burnout is my body trying to tell me it has hit a limit. I am a Black femme, a disabled writer, an organizer who has faced incredible violence, and so the truth is I am tired more often than I am not! In trying to build a career that moves at the speed of my own capacity, when the burnout comes I’ll either read a book that isn’t in the genre I’m currently writing, go for a drive without my phone (much to my fiancée’s irritation), or grab food with one of my beloveds.

Advice: As someone who walked away from a book deal and a publisher who was in conflict with my values, my needs, and my voice...listen to your inner knowing. There are a million opportunities and a million more entry points into the literary space. Trust your pen and your potential enough to only walk through doors that are right for you. The future versions of yourself will thank you for your belief and your discernment.

Finding time to write: I’m a habitual procrastinator so I typically set deadlines for myself then clear time ahead of these deadlines to write. Otherwise, I’m being shaken awake by a poem or an idea that needs to wrestle itself out of me.

Putting the book together: I worked myself into a frenzy trying to find the “perfect” organization for this collection. It was so noisy, so dense, and contained many (maybe too many) themes that acted as through lines. I was so frustrated! I printed the final version out, then decided to print two previous versions. I wanted to watch from a bird’s eye how the text had matured, to try to find ways for the order to help articulate the growth. There’s no perfect formula. Ultimately, much like seasoning a good meal, I kept poring over the pages and switching it up until an ancestor somewhere walked up behind me and whispered, Stop.

What’s next: I’m working on an essay collection about the lived experiences of young organizers in the world of racial justice who were most active between the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the death of Ma’Khia Bryant in April 2021. After seven years, I’m finally able to write plainly about the violence, the passion, the love, and the urgency alive on America’s frontlines, and how we still have so much to learn from the lives and work of the freedom fighters, the abolitionists, and the ambulance chasers.

Age: 27.

Residence: Atlanta.

Job: I am a full-time artist. I’m a writer, a speaker, a facilitator, and a community organizer, and I do consultant work for organizations that need support actualizing their commitment to equity.

Time spent writing the book: Six years from start to finish. This book has had a life!

Time spent finding a home for it: Two and a half years all told.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: We Are Owed (Grieveland) by Ariana Brown. Speechless, still. Also, The Wild Fox of Yemen (Graywolf Press) by Threa Almontaser, Poor (Penguin Books, 2020) by Caleb Femi, and Gentefication (Four Way Books) by Antonio de Jesús López.

Gumbo Ya Ya by Aurielle Marie

![]()

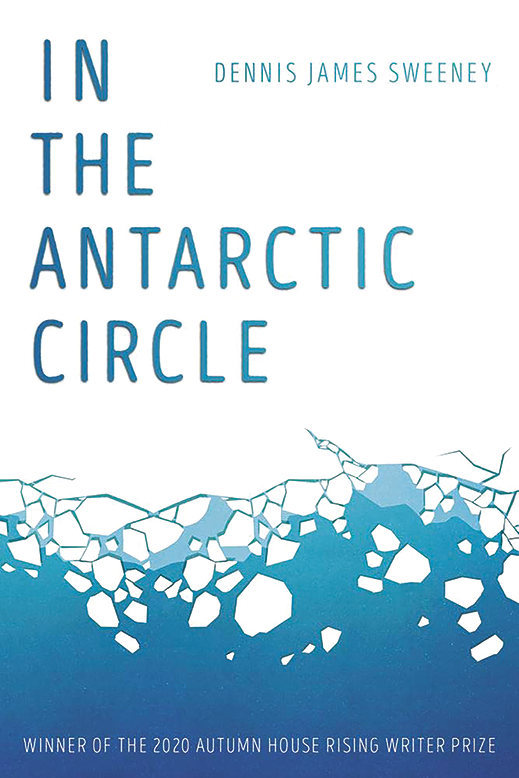

Dennis James Sweeney

In the Antarctic Circle

Autumn House Press

(Rising Writer Prize)

A heart is too found to run through.

Arrive—

The blizzard mourns fully and gently over you.

—from “75°30’S 107°0’W”

How it began: What I love about writing poetry is that I never set off to do anything. The process of In the Antarctic Circle was more like this: These moments of icy, white language arose; I followed them and explored that language space; suddenly, immersed in the cold Antarctic expanse, an ambient relationship occurred between the poems; I understood them as, potentially, “a book”; I ignored this thought for as long as possible so that I could continue to encounter the poems in a less intentional, spontaneous way; finally my own plans and ideas got the better of me, and the drafting process petered out. Only then did I allow myself to suspect that I had something.

So in a way I set off to write the book only after I had already written it.

Inspiration: The hybrid and cross-genre work published by Les Figues Press, Tarpaulin Sky Press, Sidebrow Books, Rose Metal Press, Publishing Genius, Civil Coping Mechanisms—and so many other small presses, past and present—created a community of possibility for the work I write.

Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1992) and Mat Johnson’s Pym (Spiegel & Grau, 2011) showed me how to dynamically inhabit problematic Antarctic spaces that I didn’t want to reinscribe.

Also, it helped that I have never been to Antarctica, the ostensible subject of my book, despite reading and thinking a lot about it. The continent just kept refreshing itself and never crystallized, even now.

Influences: I’ll mention just a few of the writers who had an influence on this book: Jenny Boully showed me the power of the elliptical—how language can be a footnote to something absent or off the page. Zachary Schomburg, who I was reading a lot of when I wrote In the Antarctic Circle, taught me about pleasure and play in the prose poem. I also read Emily Kendal Frey’s Sorrow Arrow (Octopus Books, 2014) when I was writing this book, and it gave me permission to live in the space between images, to find the magic there. Dorothea Lasky was the poet who began me with poetry. Hearing her read taught me to open a part of myself I didn’t know was there.

Writer’s block remedy: I usually turn to another writing project. I am lucky to have enough things going at this point that when I simply can’t work on something anymore, I put a pin in it, take a couple of notes on what I was doing, and leave it. Sometimes I leave it for years. Many things are in a continued state of being left. Then I work on something else—maybe something more analytical like revising prose, writing book reviews, or sending out work—until something itches at me to return to the thing I had left.

Advice: That old advice—never give up. But with a specific fold to it: It’s not only sending the work out that you should never give up on, but also continually refining the work, developing your approach, reading into new spaces, reevaluating yourself as a writer, critiquing the language itself, questioning your poems toward their best possible selves. Even that won’t guarantee publication. But it will at least make you feel like an active part of the process, so that sending out your work is more of a conversation than a one-way street. Your poems will continue to grow, and that’s what ultimately matters—not the fate of any particular compilation of them.

Finding time to write: These days, it’s about using the in-between spaces, letting the work be magnetic, returning to it as a form of play, as a joy, as a recovery. Weirdly, the more I’m away from my work, the more I’m excited to do it. I always want expanses of unfettered time, but when I get it, it can be really hard to feel invigorated about writing. So in a way it’s invigorating to have the opposite.

Putting the book together: I relied on many different versions of myself to do the ordering over the many years I worked on the book. There was a point when I printed out every piece and experimented with different orders by moving the pieces of paper around on the floor. That process happened intuitively—I could never quite articulate why a certain piece needed to be where it was. But seeing it from far away, “reading” the order over and over, tapped into the part of my body that just knows when a certain order or arc feels right. I love that I don’t remember now why I made the decisions I did. They feel resonant in ways that are beyond me now.

What’s next: The Last Remedy, a book of lyric essays inhabiting chronic illness through my own experience with Crohn’s.

And (secretly) more poems. I always like to pretend like I’m not working on them, that they’re just happening. Somehow that seems to better allow them.

Age: 33.

Residence: Amherst, Massachusetts.

Job: I teach at Amherst College.

Time spent writing the book: The core of the book was created over a few months: the first drafts, the images that return and return, the concept of the coordinates as titles. But the revisions and surrounding materials and organization and assembly of the book itself, plus the editorial process that I consider also a part of writing, took around six years.

Time spent finding a home for it: Five years. The book never stopped changing during that period. It only found its “final” form in the year before it was accepted.

Recommendations for debut collections from this year: This is going to involve me cheating a bit in terms of time frame, because there are several recent debuts I can’t stop thinking about. Jerika Marchan’s SWOLE (Futurepoem, 2018) blew my mind with the expansiveness and multivocal possibilities of a long poem—and seeing her perform it completely rewired my circuits. Lara Mimosa Montes’s THRESHOLES (Coffee House Press, 2020) is essay and poetry at once, a space that makes space for what is empty or at least unsaid. This year strictly defined, I loved Kylie Gellatly’s The Fever Poems (Finishing Line Press), an erasure of The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter that exposes the vulnerability of the want behind the dream of polar exploration. And Ada Limón’s debut poetry collection, Lucky Wreck, was reissued by Autumn House Press, my publisher! I was so moved to read her first published work and to see the spirit and experimentation that laid the groundwork for what she’s doing today.

In the Antarctic Circle by Dennis James Sweeney

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the name of the author of The Fever Poems. It is Kylie Gellatly.