The Smitten Author

“It’s okay to love your writing. Just don’t love your writing.” This rather quirky clip acknowledges the inevitable approach of the year’s most saccharine holiday, Valentine’s Day.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

“It’s okay to love your writing. Just don’t love your writing.” This rather quirky clip acknowledges the inevitable approach of the year’s most saccharine holiday, Valentine’s Day.

The award-winning poet and former poet laureate is seen here reading three poems at the 2008 Dodge Poetry Festival. Kumin passed away on February 6 at the age of eighty-eight.

The author most recently of Gossamurmur (Penguin, 2013) reads from "Manatee/Humanity" as part of Poet-to-Poet, an educational project from the Academy of American Poets for National Poetry Month 2014.

PBS NewsHour's Jeffrey Brown recently talked with Carolyn Forché, whose new anthology, Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English 1500-2001, published last month by W.W. Norton, contains the work of poets who have witnessed war, imprisonment, torture, and slavery. Forché calls the collection an "outcry of the soul."

“The most wasted of all days is one without laughter,” wrote E. E. Cummings. Timing is important both in comedy and in poetry. Though poets often engage with serious subjects, a well-placed moment of levity can make a poem even more poignant. This week, try to incorporate humor in your own writing. It can be a funny image, a pun, or a parody. See how this moment affects the tone of your poem, or how it leads you in a new, unexpected direction.

"How lovely it is to write with all these vowels." The latest short film from Motionpoems features Robert Bly's poem "The Watcher of Vowels," with design and animation by Matt Van Ekeren.

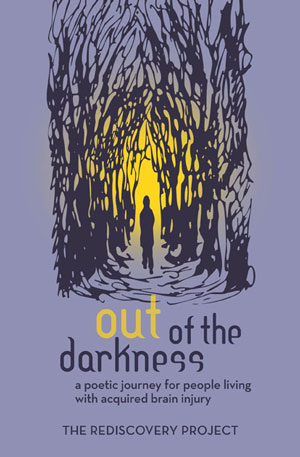

Krista Wissing is a licensed therapist who has facilitated expressive arts therapy experiences for people impacted by brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, medical illness, addiction, co-occurring disorders, and trauma. She founded The Rediscovery Project in 2012 and is currently the Day Program Coordinator for Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area. Expressive writing has been critical to Krista’s own healing process, and her work has appeared in The Molotov Cocktail, Bitchbuzz.com, and Know Journal (upcoming). She recently taught a workshop for people with brain injuries at the Institute for Poetic Medicine in Larkspur, California. We asked her to blog about the experience.

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be.

In my years of working with people who’ve experienced an acquired brain injury (ABI), I often hear how destabilizing and isolating the cognitive, emotional, social, and physical aftermath of ABI can be.

The thing about ABI is that nine times out of ten there is no warning. Be it a head trauma, stroke or a virus attacking the brain, ABI barrels in like an unexpected wind and divides one’s life narrative into two—life before and life after brain injury.

It’s the kind of phenomena that rocks one’s foundation to the core.

It’s the kind of phenomena that leaves the bearer asking tough questions. Why did this happen to me? What kind of life lies ahead? Where and with whom do I belong? And what of my dreams? My purpose? My identity? My faith?

My Right Arm

Blake Herod

My right arm was my buddy. Grade school

rock and ball throwing. Nose

and scab picking. Young breast holding

nipple rolling. Holder of all the

body making, body destroying

drugs, liquor, food, for a good time

call, wait a minute, hold this.

Can you climb all the way to the

top, gesture drawing, paintbrush holding

steering wheel with three on the

tree, 5-speed, with granny gear,

floor shifting, board paddling wave

riding. Pool lap swimming. Nail pounding,

board lifting, torch holding, bike riding,

throttle whacking, old buddy.

My future by building the foundation.

Now it’s not.

It’s the kind of life-altering experience that holds the transformative potential of the Hero’s Journey and merits the healing elixirs of poetry, art, and community.

This is the heart and soul of the Rediscovery Project, a ten-week group that supports ABI survivors in uncovering their own Hero’s Journey through poetry and expressive art. The project culminates by bridging project participants with the community at large through a public poetry reading and print anthology.

The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter.

The project was conceived of in 2011 during a discussion I had with poetry therapist John Fox, CPT. Years earlier, during grad school, I attended John’s poetry therapy class and felt an affinity for his work with poetry as healer. By 2012, John’s organization, Institute of Poetic Medicine, was on board to graciously fund the program. Rediscovery Project was launched later that year at Brain Injury Network of the Bay Area and continued in 2013, thanks to funding from Institute of Poetic Medicine, P&W’s Readings/Workshops program, and Bread for the Journey-Marin Chapter.

When people who suffer come together to heal, magic happens. To bear witness to this is sacred. If we listen closely and with care, what might we hear? If we lean in, what might we feel? Might we hear the Hero’s call to adventure—its cadence, pulse, and urgency? Might we feel its gravitational pull, even at its most tentative, to life experiences that shake, shift, and shape us?

And when we finally wake up to our own Hero’s Journey, how do we explore the truth of what brings us here today?

Mosaic

Philippa Courtney

The white wolf wails inside my soul,

cries in the darkness—Make me whole.

Summon the shaman.

Fan the flame.

Scatter the ashes—chant my name.

Gather the pieces, shard and sliver

silent brain cells in a quiver

Fly like an arrow through the night.

Sparks ignited;

second sight.

Broken open,

given form.

Lose it all; be reborn.

Photos: Top: Krista Wissing. Credit: Kari Ovik. Lower: the anthology of work by participants in Wissing's classes.

Major support for Readings/Workshops in California is provided by The James Irvine Foundation. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

The Poetry Society of America (PSA) has announced that poet Gerald Stern will receive the 2014 Frost Medal, the organization’s most prestigious award, given annually for distinguished lifetime achievement in poetry.

The son of immigrants from Poland and Ukraine, Gerald Stern was born in 1925 in Pittsburgh. He is the author of eighteen books of poetry, including most recently In Beauty Bright (Norton, 2012), as well as two chapbooks and four essay collections. His collection This Time: New and Selected Poems, received the National Book Award in 1998, and in 2000 he was appointed the first poet laureate of New Jersey. Among numerous other accolades, he has also received the Wallace Stevens Award from the Academy of American Poets, and was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He studied at the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia University, and has taught literature and creative writing at Temple University, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Drew University, and the Iowa Writers' Workshop. He lives in Lambertville, New Jersey.

Stern will be honored, along with the recipients of PSA’s annual Shelley Award, Chapbook Fellowships, and a number of other annual poetry awards, at a ceremony on April 9 in New York City. Admission is free and open to the public.

Previous Frost Medal winners have included Robert Bly, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lucille Clifton, Robert Frost, Allen Ginsberg, Marianne Moore, Marilyn Nelson, Charles Simic, and Wallace Stevens.

In the video below, Gerald Stern reads his poem “The Dancing” for Public Television’s Poetry Everywhere series.

In an effort to celebrate great books of long ago that were overlooked by major American literary prizes such as the National Book Awards and the Pulitzer Prizes, online literary magazine Bookslut has launched its own new award.

The Daphnes will posthumously honor books published decades ago, starting with the year 1963, in order to “right the wrongs of the 1964 National Book Awards," editor Jessa Crispin writes on the Bookslut blog. “If you look back at the books that won the Pulitzer or the National Book Award, it is always the wrong book. It takes decades for the reader to catch up to a genius book, it takes years away from hype, publicity teams, and favoritism to see that some books just aren’t that good.”

The Bookslut team has begun compiling nominations of some of the best books published in 1963—very few of which even made the NBA shortlist—which in fiction included The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, V by Thomas Pynchon, and Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, among others (John Updike's The Centaur took the fiction prize that year). Notable nonfiction works of the year included Fire Next Time by James Baldwin and Eichmann in Jerusalem by Hannah Arendt (the award went to a biography of John Keats); and while a John Crowe Ransome anthology took the prize in poetry, other 1963 collections included 73 Poems by E. E. Cummings, Reality Sandwiches by Allen Ginsburg, Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law by Adrienne Rich, and All My Pretty Ones by Anne Sexton.

The editors are currently seeking more nominees for the best books of 1963, in the categories of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and children’s books. Nominations can be sent via e-mail to Jessa Crispin.

A panel of judges in each category, comprised of writers chosen by the editors, will read each nominated book and vote on the winner.

Stay tuned to the Bookslut blog for more updates about the award, and in the meantime check out an interview with Crispin by Dustin Kurtz of independent publisher Melville House.

“The poet is the priest of the invisible,” wrote Wallace Stevens. This week, try to write about an invisible force that affects you deeply. For example, it could be your DNA, music, or the smell of your childhood home. Try to imagine the complexity of the invisible (at least to the naked eye) structure that you are describing. Integrate all of your senses to navigate its visual formlessness.