Koon Woon’s Lessons from Uncle Sum

P&W-supported poet Koon Woon, October’s Writer in Residence, was born in a timeless village in China in 1949. In 1960 he immigrated to Washington State, first to the logging town of Aberdeen, then to Seattle, where he now resides. He turned to poetry while he was a mathematics and philosophy student coping with mental illness. Later he attended the workshops of Nelson Bentley at the University of Washington. At the age of forty-eight, Koon’s first book, The Truth in Rented Rooms, was published by Kaya Press.  My Uncle Sum was my second maternal uncle and my mentor, a man of three teachings: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. He told his wife that the proper place to wash his clothes was at the river by the ancestral shrine, the part of the chicken to give their nephew was the thigh, and the way to regulate the household was to avoid unnecessary noise.

My Uncle Sum was my second maternal uncle and my mentor, a man of three teachings: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. He told his wife that the proper place to wash his clothes was at the river by the ancestral shrine, the part of the chicken to give their nephew was the thigh, and the way to regulate the household was to avoid unnecessary noise.

He told me that the short pines behind his house in the village could be used to make furniture for newlyweds. Their scent, he said, would lure the Shaolin Buddhist monks, but the way to fight is by avoiding fights. The way to use an abacus is to balance equals with equals, the ebb and flow of the Tao. He read me stories in our Canton flat. He signed his name to my school report cards when my father was faraway in America.

Literature comes from great love—love for stories and books, love for the unseen and the invisible, but mostly love for humanity. My Uncle Sum taught me those things, and when I won my first literary prize, he told me that was the time to work even harder.

In taking my cues from Uncle Sum, I stood in opposition to my pragmatic father, who labored to support his wife and eight restless children. After I joined him in the United States, we lived in the housing projects. At one point, he worked as a fry cook for a restaurant owned by the mayor. Another time, he was forced to take a job at a restaurant that fronted a whorehouse, where I helped him in the kitchen until the wee hours of the morning. It was a traumatizing experience (and no doubt a contributor to my struggle with mental illness), which I blocked out as I hit the school books, became the literary chair of my high school, and won a science scholarship.

But that’s only part of my journey to becoming a poet. Here are my instructions for the rest: After a promising career as a student, begin a slow descent into the hell of mental illness. Live in flea bag hotels or on the street. Get confined to psychiatric hospitals and jails. Live in tenement rooms with a sink in the corner and a hotplate to cook pinto beans and bacon rinds, reading the poetry of Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, and Anne Sexton while not caring if your soul survives. Labor under the glare of a bare bulb trying to write as tenderly as Pablo Neruda and as daringly as Cesar Vallejo. You won’t have money, but you will have a strange, unshakable optimism about humanity.

The latter is what I learned from Uncle Sum. When he was across the Pacific dying of liver cancer, I was starting my life as a poet. I felt like I was drowning in shallow water. But armed with poetry, I survived, as strong as a cockroach.

Everyone wants to win the Yale Younger Poets prize or the Pulitzer. But even winning the Nobel does not guarantee nobility of soul. As I said before, I write because I have to. It is the exorcism of all that is still immature in me.

Photo: Koon Woon reads with Beacon Bards at the Station coffee shop in Seattle. Credit: Greg Bem

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Seattle is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

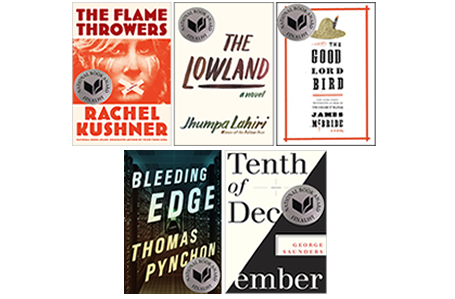

The finalists in poetry are Frank Bidart, Metaphysical Dog (Farrar, Straus and Giroux); Lucie Brock-Broido, Stay, Illusion (Knopf); Adrian Matejka, The Big Smoke (Penguin); Matt Rasmussen, Black Aperture (Louisiana State University Press); and Mary Szybist, Incarnadine (Graywolf Press).

The finalists in poetry are Frank Bidart, Metaphysical Dog (Farrar, Straus and Giroux); Lucie Brock-Broido, Stay, Illusion (Knopf); Adrian Matejka, The Big Smoke (Penguin); Matt Rasmussen, Black Aperture (Louisiana State University Press); and Mary Szybist, Incarnadine (Graywolf Press).

My most recent reading in Seattle—a production of the Chrysanthemum Literary Society with support from Poets & Writers, featuring several

My most recent reading in Seattle—a production of the Chrysanthemum Literary Society with support from Poets & Writers, featuring several  It might sound like a stretch, but poetry saved my life—along with the care of psychotherapists, the kindness of my dear friend Betty Irene Priebe, and a continuous parade of literary friends.

It might sound like a stretch, but poetry saved my life—along with the care of psychotherapists, the kindness of my dear friend Betty Irene Priebe, and a continuous parade of literary friends.