Daniela Jungova is the Development & Communications associate at Calvary Women’s Services, the award-winning organization that empowers homeless women in Washington, D.C., to transform their lives through housing, health, education, and employment programs. She feels lucky to have had the opportunity to witness the inspiration that poetry offers to women overcoming homelessness.

“Poetry is people conveying their dreams through words,” mused Sonja Berry, who attended all three of the Echoes in These Streets poetry readings at Calvary Women’s Services—an award-winning organization empowering homeless women in Washington, D.C.

The P&W–supported reading series took place over the course of three beautiful summer Sundays (July 9, 16 and 30) and featured five outstanding poets from the D.C. area—Teri Ellen Cross Davis, Hayes Davis, Katherine McCord, Saundra Rose Maley, and Nancy Arbuthnot. The poets were selected for their cultural relevancy, as well as the ability to connect with diverse populations—the majority of women living at Calvary are survivors of domestic violence, are learning to manage a mental illness, and/or are in recovery from substance abuse.

The P&W–supported reading series took place over the course of three beautiful summer Sundays (July 9, 16 and 30) and featured five outstanding poets from the D.C. area—Teri Ellen Cross Davis, Hayes Davis, Katherine McCord, Saundra Rose Maley, and Nancy Arbuthnot. The poets were selected for their cultural relevancy, as well as the ability to connect with diverse populations—the majority of women living at Calvary are survivors of domestic violence, are learning to manage a mental illness, and/or are in recovery from substance abuse.

For many women facing similar challenges, closing up to the world is an easy way to cope. Berry, who came to Calvary four months ago, says that the poets’ openness was a true gift: “Seeing the poets describe reality in metaphors made me feel inspired, and, well, curious.”

Indeed, all five of the presenting poets got quite personal. Their poems tackled issues such as ordinary life, identity, depression, stereotypes, fatherhood, even breastfeeding. Some delivered their works boldly, fearlessly offering their musings to the world. Others invited the audience to an intimate conversation, softly whispering as if to a best friend. All of them though, voiced their inner thoughts in a genuine and relatable way.

Hayes Davis wrote in his piece “Musings”: “One myth that’s part truth / is men don’t always share sadness that rests / on a foundation of vulnerability.” In “Gaze,” Teri Ellen Cross Davis wrote: “Standing, I name myself / shedding the fiction of availability / becoming nonfiction.” In her piece about islands, Katherine McCord contemplated: “After all, swimming is all / luck. We have no gills / and islands are all light. / Escape that.” Saundra Rose Maley described a hot summer night scene in “First Blues”: “Televisions gone bleary / blinked / in front of men / in undershirts drinking beer.” In “Song,” Nancy Arbuthnot observed: “The best things are nearest / breath, light, flowers / the path just before you.”

Arbuthnot, a poetry teacher at the Naval Academy and longtime volunteer at Calvary Women’s Services, says most of her poems, like the one above, explore everyday life, spirituality, and the way we confront major life issues. Perhaps that’s why her poems resonated so strongly with women at Calvary. She feels the same way about them: “Echoes in These Streets was held on Sundays, and attendance was voluntary. The women who showed up were clearly very interested. They were an incredibly receptive audience, which is what every poet certainly appreciates. It’s been delightful—it made me wonder who really is giving and who is gaining.”

Echoes in These Streets brought much joy and inspiration to women at Calvary, who have long enjoyed experimenting with their own creative abilities. Even though the reading series is over, women at Calvary will have the support they need no matter what artistic endeavor they decide to undertake in the future—Calvary’s literacy and arts program, LEAP, runs year-round and is designed to empower women in understanding and using their own talents and strengths.

Elaine Johnson, who coordinates LEAP and witnesses women’s artistic sides firsthand, noted: “Echoes in These Streets deepened women’s relationship with writing. At the last session, the women were discussing the idea of continuing to meet on Sunday evenings to share and discuss their own poetry—and I see that as evidence of the lasting effect of the series!”

Elaine Johnson, who coordinates LEAP and witnesses women’s artistic sides firsthand, noted: “Echoes in These Streets deepened women’s relationship with writing. At the last session, the women were discussing the idea of continuing to meet on Sunday evenings to share and discuss their own poetry—and I see that as evidence of the lasting effect of the series!”

Nancy Arbuthnot agrees: “I think it’s really great that Poets & Writers makes it possible for poets to go out to communities like Calvary. Echoes in These Streets clearly showed that the audience and poets alike benefit from these readings.”

The staff and residents of Calvary Women’s Services would like to thank everyone who participated in the readings and savored poetry as a tool for self-expression, empowerment, and acceptance. A sincere thank you also goes to Poets & Writers who made it possible for the five brilliant poets to present their work to women at Calvary. There is no way these three wonderful evenings would have been possible without your generous support. Here at Calvary, your gift of poetry will certainly keep on giving.

Support for Readings & Workshops in Washington, D.C. is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

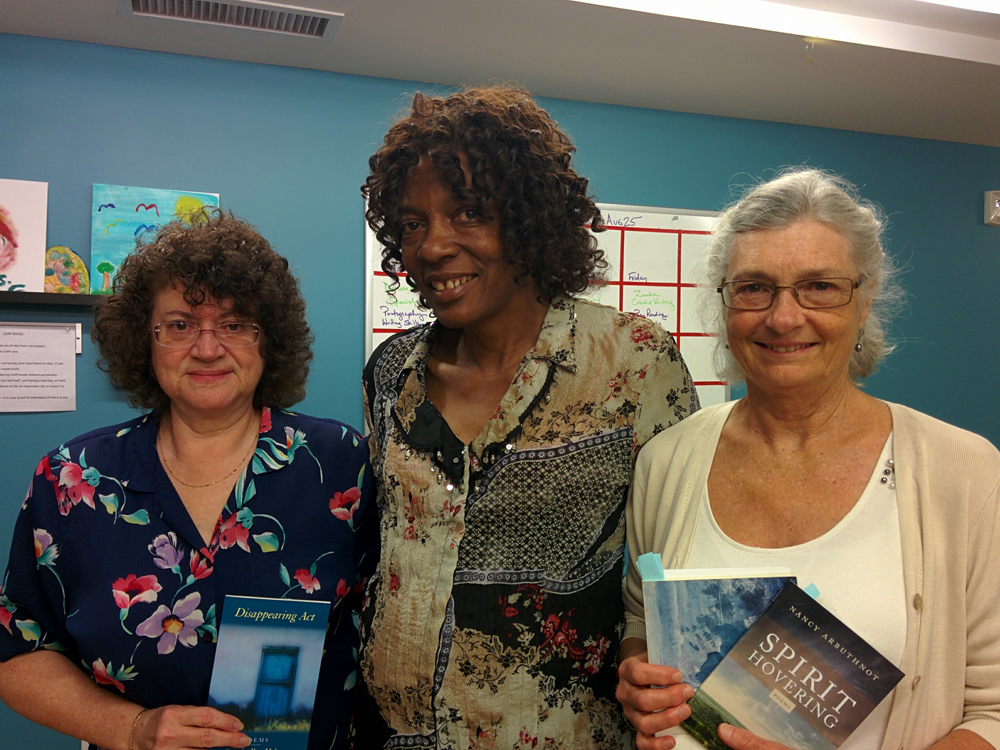

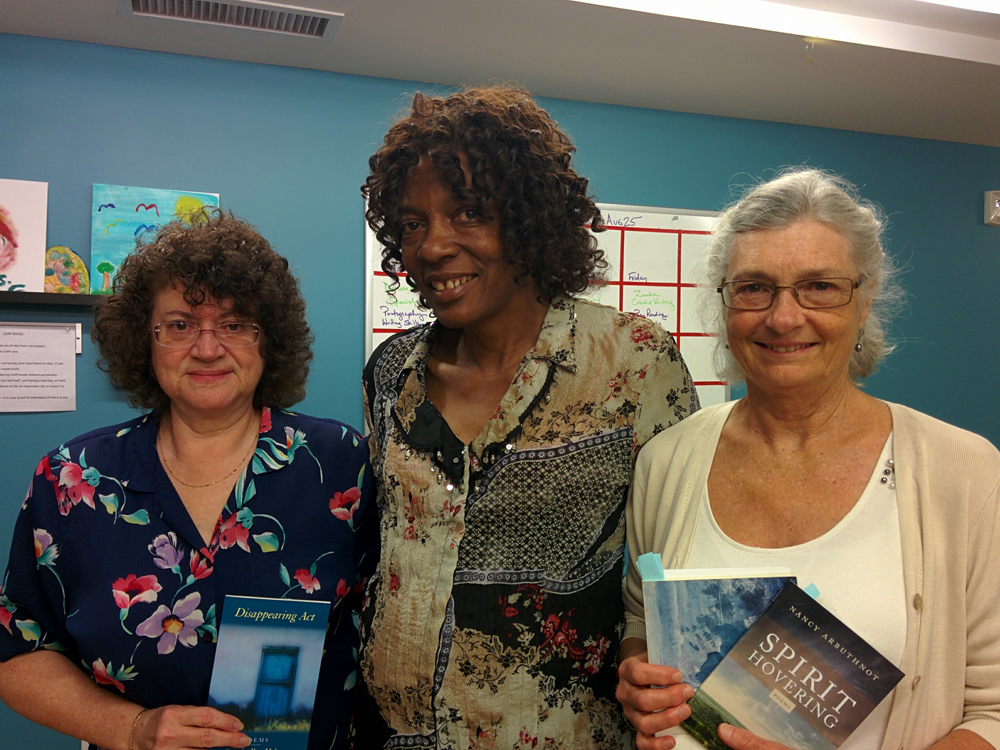

Photos: (top) Hayes Davis, Sonja Berry, and Teri Ellen Cross Davis (Credit: Elaine Johnson). (bottom) Saundra Rose Maley and Nancy Arbuthnot with audience member (Credit: Elaine Johnson).

The P&W–supported reading series took place over the course of three beautiful summer Sundays (July 9, 16 and 30) and featured five outstanding poets from the D.C. area—Teri Ellen Cross Davis, Hayes Davis, Katherine McCord, Saundra Rose Maley, and Nancy Arbuthnot. The poets were selected for their cultural relevancy, as well as the ability to connect with diverse populations—the majority of women living at Calvary are survivors of domestic violence, are learning to manage a mental illness, and/or are in recovery from substance abuse.

The P&W–supported reading series took place over the course of three beautiful summer Sundays (July 9, 16 and 30) and featured five outstanding poets from the D.C. area—Teri Ellen Cross Davis, Hayes Davis, Katherine McCord, Saundra Rose Maley, and Nancy Arbuthnot. The poets were selected for their cultural relevancy, as well as the ability to connect with diverse populations—the majority of women living at Calvary are survivors of domestic violence, are learning to manage a mental illness, and/or are in recovery from substance abuse. Elaine Johnson, who coordinates LEAP and witnesses women’s artistic sides firsthand, noted: “Echoes in These Streets deepened women’s relationship with writing. At the last session, the women were discussing the idea of continuing to meet on Sunday evenings to share and discuss their own poetry—and I see that as evidence of the lasting effect of the series!”

Elaine Johnson, who coordinates LEAP and witnesses women’s artistic sides firsthand, noted: “Echoes in These Streets deepened women’s relationship with writing. At the last session, the women were discussing the idea of continuing to meet on Sunday evenings to share and discuss their own poetry—and I see that as evidence of the lasting effect of the series!”