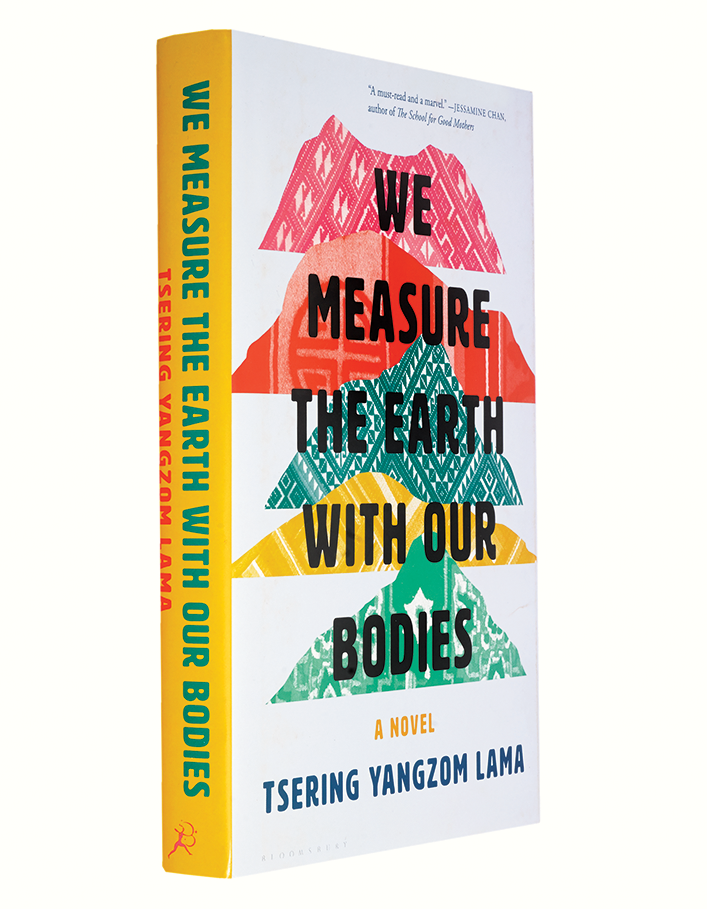

Tsering Yangzom Lama, author of the novel We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies, published in May by Bloomsbury, introduced by Tsering Wangmo Dhompa, author of four books, most recently Coming Home to Tibet: A Memoir of Love, Loss and Belonging, published by Shambhala Publications in 2016. (Credit: Lama: Paige Critcher; Dhompa: Ron Srinivasan)

![]()

Tsering Yangzom Lama’s debut novel, We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies, feels like a place I’ve lived all my life, or maybe it’s a place I’ve been waiting to live in. Lama’s novel is groundbreaking, and not just because the anglophone novel is a more recent feature of Tibetan literature. We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies begins in 1960 with the novel’s three main protagonists, Ama and her daughters, Lhamo and Tenkyi, being thrust into a life in exile in the wake of China’s invasion of Tibet. With heartbreaking clarity the novel explores the slow recovery of self, memory, and place.

Lama’s masterful control over a plot that covers more than fifty years exposes how displacement is never a singular event. She is precise in her writing about the tumult that encapsulates the life of her protagonists. “People find our culture beautiful,” but “not our suffering,” she writes in the voice of Dolma, Lhamo’s daughter, speaking to Samphel, a man whose life is entangled with that of the three women. In Lama’s saga of love and sacrifice, there is no romance to exile. We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies offers a way to believe that the land will persist and, with it, those who long to return to homelands stolen from them.

The title We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies lingers in me. Can you tell us a bit about how you came up with this title?

It refers to the ancient practice of making a pilgrimage through full-body prostrations, which is still alive among Tibetans. As you know, this is a method of prayer in which the pilgrim advances slowly, lying on the ground and rising, each step the length of their outstretched body. I was struck by this ritual because it conveys so much about how Tibetans relate to the land—intimately and corporally, showing reverence and connection to the earth. Land is so much more than just soil between borders. For Tibetans our land is home to gods and spirits. When we are displaced, or restricted in movement as Tibetans are in Tibet, we experience many forms of violence, including one of spiritual dispossession. This is what I explore in my novel—these underrecognized effects of occupation and exile.

My novel’s title also refers to the slow and difficult journeys that refugees make across the earth in search of safety and refuge. These are not theoretical or romantic journeys, but the embodied struggles of everyday statelessness and dispossession from one’s homeland. But even when the characters have been exiled from their homeland for decades, their bodies remain connected to that lost home. This is why the notion of home is painful but also why it’s impossible to abandon.

Your mention of gods and spirits takes me to the novel’s opening, when we discover that Ama, one of the central characters, is an oracle. Narratives of men as oracles tend to dominate our stories. Was Ama always an oracle as you began to see her as a character?

It’s true that the most famous oracles in Tibet are usually men who are institutionally associated with monasteries, even directly advising our leaders. But with this novel I wanted to focus on the lives of ordinary Tibetans, far from the centers of power. I first became interested in female oracles when I read the scholarly essay “Female Oracles in Modern Tibet” by Hildegard Diemberger. I learned that in remote places, female oracles could be among the only figures that a community could turn to in a crisis—not only to make premonitions, but for healing, counseling, even mediating issues.

I was also interested in oracles because they’re figures of crisis; they are natural guides in moments of turmoil and uncertainty. As an individual, the would-be oracle also experiences personal crisis in their initiation. If they’re able to survive this personal crisis, they can go on to help their community through collective crises. This interplay between the personal and collective is a recurring theme in my novel. Finally, I was drawn to the idea of having a strong woman animate the story of the invasion of Tibet. There’s something powerful in reframing that historical moment with a woman at the center.

There’s also the interplay between personal struggles and collective struggles: colonization, ecological collapse, dispossession. Did you have to do much research to write this novel?

Writing this novel I became omni-curious in my study of our people and history. It was a slow reconnection with a country that colonization and exile have denied me. I like to think the research was a way for me to build a bridge back to the past, to my ancestral home.

At the same time I had real structural limitations to contend with. I could not enter Tibet; my source materials were limited mainly to scholarly materials in research libraries, and even those I was frankly lucky to be able to access. All this is heightened by the fact that Tibet’s history is being erased or rewritten as part of China’s ongoing colonial project. So I had to get creative and work slowly, rewriting every time I learned something new.

In terms of the specifics, I trekked to the border of Nepal and Tibet so I could experience the landscape and people there and envision the refugee’s journey. I interviewed scholars, traveled to Dharamsala, India, to learn about the early days of the Tibetan government in exile, and referenced the Tibet Oral History Project for first-person accounts from the generation that fled Tibet or fought in the resistance. I also spent about a year making regular trips to the stacks at Columbia University’s various libraries. But at a certain point I had to begin inventing because I was writing a work of fiction.

As I was reading your novel, I was thinking of the more than 4 million refugees from Ukraine since the Russian invasion, and of the more than 70 million refugees and displaced people around the world. What were some of the questions or stories that were important to you or that were important to writing this novel?

My grandparents were nomads from Ngari, in western Tibet. My parents were refugees who lost everything when they fled for Nepal. I have lived in Nepal, the United States, and Canada. All of this upheaval happened over just a few decades, and this is a typical story for so many Tibetans living in exile. Meanwhile Tibet remains under military occupation by one of the most powerful and brutal regimes on the earth.

And yet we have persisted. Our sense of identity and solidarity remains, even for young Tibetans who have never seen a free Tibet. I wanted to know how we survived this profound upheaval, how it has changed us.

You’ve worked as a writer in many different genres. What does the novel make possible that other forms might not?

I wrote a short essay about my research trek to the border of Nepal and Tibet for the Kenyon Review, but this story has always been fictional and specifically a novel. A novel gives both the writer and the reader freedom to spread out and to dig deep at the same time. Fiction allows us the closest approximation of becoming someone else. We can see their memories, their dreams. We can experience their mind at work and feel what it’s like to live in another body. It’s an inherently empathic endeavor to read or write fiction.

An excerpt from We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies

Border of Western Tibet and Nepal

Spring 1960

Ama was an oracle. The realization came to my mother late in life, when her monthly bleedings stopped and something else opened inside. Some in our village called it an affliction. They said there was a crack in her mind that left her open to spirits who would consume her. But Ama insisted it was a blessing to lend her body to the gods and allow them to speak through her. In time, everyone would listen, and the words of an otherwise ordinary woman would lead us through the coming troubles.

It wasn’t just my mother who had changed. Packs of wolves and rats swept through our valley. Next, there was an earthquake that tore a jagged line through our village monastery. Then, just as I was learning to speak, there came news that invaders had crossed our border, entering our land as two enormous snakes. In the distant town of Kardze, people watched them cross the river in long lines and burrow into the highlands. They wished to be called the People’s Liberation Army, but we knew them as the Gyami, a people from the lowlands to the east.

In the years that followed, rumors came like crows, even traveling as far west as our village. Although I was just a young girl, many of the rumors landed in my ears before anyone else in my family. My source was Lhaksam, my oldest friend. He worked as a servant to a traveling merchant who traded in gossip as much as iron pots and pans. In our free moments, Lhaksam and I wandered in the pastures with my little sister

Tenkyi hanging on my back or flopping around in the grass. In those hills, Lhaksam told me the most shocking stories. Gyami soldiers had seized farmland in the east, and many of our people were now starving. No grain, no salt, no meat or even butter. I walked around in a daze after hearing this, unable to imagine life without butter. Lhaksam said that although it was quiet in our region, a resistance raged in the east, in places where iron birds circled the skies and bullets big and small rained down on entire towns, smashing bodies as if they were nothing but effigies made of dough, where rooftops were torn apart and no one could tell whether they had found the remains of a loved one or that of a stranger. But I did not tell my family these things. I never repeated them to anyone.

Then, last spring, our village heard of a terrifying ruse: a plan to lead the Precious One into the dragon’s home. Hearing about this trap, thou- sands of our people in Lhasa gathered outside the summer palace, forming a protective circle with their bodies. Even as the soldiers neared and the scent of gunpowder swirled in the air, our people refused to leave. To prevent a massacre, the Precious One disguised himself as a commoner and fled south by night to another country. So did the great Nechung Oracle, who had divined their escape route through the mountains. When the foreign troops learned that our leader had slipped away, they pierced the crowd with bullets and lined the streets with corpses.

After the Precious One left, the sun was erased from our skies. Flowers refused to bloom, and our yaks made no milk. In that darkness, every family in our village wondered if it was time to leave, to follow our leader to the lowlands until the day when it would be safe to return. Others recited a bleak, ancient prophecy: When the iron bird flies and horses run on wheels, the People of Snows will be scattered like ants across the face of the earth.

It was that day, nearly ten years after revealing that the gods had spoken to her, when Ama said to us, “Now is the time. I must give my body to the spirits.”

From We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies. Copyright © 2022 by Tsering Yangzom Lama. Excerpt by permission of Bloomsbury.