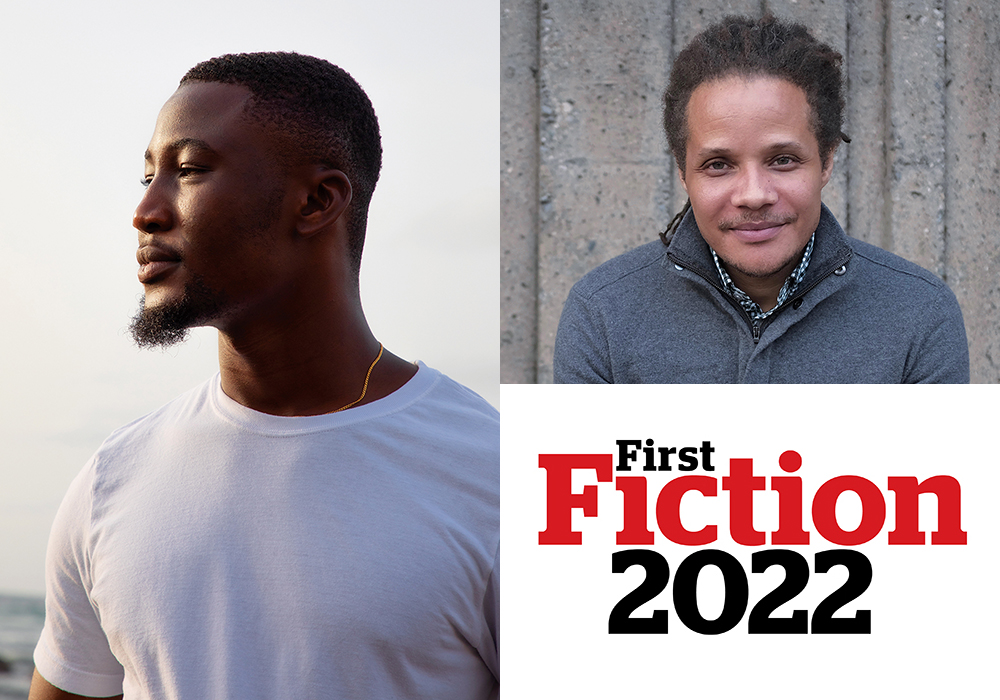

Arinze Ifeakandu, whose debut story collection, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, was published in June by A Public Space Books, introduced by Jamel Brinkley, author of the story collection A Lucky Man, published by Graywolf Press in 2018. (Credit: Ifeakandu: Bec Stupak Diop; Brinkley: Arash Saedinia)

![]()

One of the stories in Arinze Ifeakandu’s debut, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, describes a character who tells lies “to avoid being known.” It struck me that the knowability or unknowability of a person is among the threads that bind this new collection, which is a testament to the layered complexity of the book’s characters. These characters are navigating a world of uncertainty, one in which their power and safety often depend on an ability to disguise their queerness, a central aspect of who they are. I read the book with great admiration for every instance of particularized attention it gives to the aches and tensions that are inherent to the fact of being alive. These characters seek to protect themselves, but they also, just as urgently, act on their desires for the kinds of connections that allow love and happiness to flower.

The collection is remarkable for its truth-telling, which is delivered to readers as a rich but subtle singing on the page. Given the author’s own background and experience as a choir singer, perhaps this musical quality isn’t a surprise. It’s clear in any case that this book is the introduction to a voice of distinction and significance, one I hope to hear for a very long time.

Your stories do not shy away from depicting bodies, physical intimacy, and sex. Those depictions are, in my mind, one of the hallmarks of the collection. Can you talk about the thought process behind your approach to this subject matter in the stories?

Depicting sex, bodies, and physical intimacy was a part of the collection’s larger project of depicting life’s moments in fullness, the collection’s fidelity to a keen sort of realism. I wanted my characters to feel as real to readers as people familiar to them. When I read certain books I am stunned by this familiarity. This is a book about youth, among many other things, and sex is as present in my life, and in the lives of the young people I know, as work and family are: We consume sex, talk about it, have it, understand its seriousness as well as its frivolousness. As we walk through streets we encounter people first as bodies. We think, “He’s hot.” Or, “She’s so tall.” Or, “They smell like onions.” We react to the bodies of others, communicate, or show levels of intimacy by using our bodies in specific ways. A character’s presence is conveyed by stuff like backstory and forays into their psyche, but I think it is the body in action—physical attributes, yes, but more important how bodies react to, or interact with, one another—that conveys it most.

I was fascinated by the treatment of memory and time in your stories, and I’d love to hear your thoughts about it.

Memory and time have a harmonious relationship, in that memory serves as the vehicle through which time travels. In writing about loss and home, meaning is at the center of things; in life we revisit memories that we have designated, consciously or unconsciously, as meaningful, whether for happy or tragic reasons. I am deeply nostalgic—less keenly now than years ago when I wrote these stories—and I wanted that feeling of nostalgia, which involves a certain melancholy, to permeate the atmosphere of each story. I knew that it was by remembering, and by giving textures to these remembrances, that this was possible.

Your prose is so lush and light. What’s your approach to the sentence and/or the paragraph? Are there any influences of note?

Beauty is at the center of my thinking about sentences. As I write I am propelled by rhythm and flow. One sentence leads to another as a way of getting somewhere: the next paragraph, page, or, most often, the truth of an idea or emotion. Language, taken seriously—and play is a part of this seriousness—gifts its wisdom to us, which is my understanding of what Garth Greenwell once said in a workshop. I want to be able to tease the reader toward a set of ideas, moods, or feelings. My experience in choir taught me intentionality in this regard, to treat punctuation marks like a composer’s directions saying tenderly or poco a poco. I think of paragraphs as units: of ideas, arguments, emotion, or action. A paragraph carries the biggest pause, the dramatic kind that says, without uttering it aloud, furthermore; nevertheless; however.

After reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie as a teenager, I knew I wanted to write beautifully—she was my first introduction to that undulating rhythm. Chinua Achebe and Buchi Emecheta before her were direct and quick and were more concerned with telling the story, a different kind of immersion. When I read Greenwell’s What Belongs to You a few years ago, I saw the strange, enticing use of commas and loved it.

You were one of A Public Space’s emerging writer fellows, and now your debut is being published by that magazine’s book imprint. What have been the highlights of the journey from fellow to debut author?

One highlight, I’d say, was meeting Salvatore Scibona, who was my mentor for the fellowship. When he came to read at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he reminded me that nobody—no matter how much respect I had for them—should have the power of dictating how I felt about my own story. Another highlight is being shortlisted for the Caine Prize, which led me to the Caine workshop in Rwanda the year after. Gisenyi continues to be a wonderful memory. Then I went to Iowa, and now this, my book in the world. The fellowship feels to me like the beginning of this present life.

Speaking of journeys, how would you describe the one this book takes readers on from beginning to end? How do you see the stories speaking to one another, and did any of this change at all as the book was being edited and prepared for publication?

While writing these stories I was anxious about repeating myself. I was thinking in terms of large, overarching themes such as love, loss, and country, and using what felt like the same material—men in love with others—and worried that this had created a problem in which every story was the same. I began to see that this was not the case, that my characters and their stories were varied as a result of their unique situations and biographies, but it was not clear to me yet just how varied, until editing began. The stories are tied together for me by the idea of home, as person, place, or thing, and by the fact that the characters are always looking, searching for, and often choosing home. I began by thinking I wanted to write a book of gay love—the travails, obstacles, joys, and sadness—and about the Nigerian condition, and in my mind the answer was tragic. But there was life and love in abundance, and therein lay the hope. Again, I knew this, but editing helped me believe it, and that impacted the way I approached the stories for finishing touches.

A excerpt from “What the Singers Say About Love” from

God’s Childern Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu

I.

I’d seen Kayode once before, in first year, having a bath downstairs, his wet body an assemblage of small perfect muscles, his ass firm and flawless, his dick, my God. I noticed him in the way that one notices something beautiful but unattainable and did not see him again until second year, when I went with my friend Ekene to a campus celebrities’ bash. He was going from group to group, talking, swaying to the music, and I only recognized him as someone I’d seen before but did not know, until I heard someone say his name. Ekene had talked about him a few times in the past, this handsome boy who made beautiful music. I sat in a corner of the room, watching people dancing, thinking how happy their lives were in that moment, how tomorrow this senseless joy would be absent. His eyes caught mine watching him. He looked puzzled, a look that, with most boys, usually turned into aggression. I glanced away.

When I looked back up, he was staring at me. I smiled, unsure of how to read and return that brazen stare. He smiled back, whispered something to a girl who was deep in conversation with Ekene, and she nodded, a quick, distracted nod. He strode toward me, holding a can of Star, which he placed on the table as he sat opposite me. I noticed, for the first time, the tiny gleaming silver stud in his right ear.

You seem to be having so much fun, he said, smiling. He had the whitest teeth.

You’re teasing me, I said.

Oh no, I’m not, he said, lifting his arms innocently, and for a moment I believed him, but then he smiled widely and asked, Why aren’t you dancing?

I can’t dance, I said, shrugged.

He arched his eyebrow. The song playing now was loud, was full of clanging metal, of booming drums, and the dancers had gone completely mad, jumping and shaking their heads like people about to burst into incantations. When he spoke, he had to shout: Everybody can dance.

Not me, I said. I dance like a girl.

You what?

He leaned in and I leaned in, my lips to his ear. His hair had a distant scent, of something sweet and fruity. I imagined him in the bathroom, his head crowned in lather. Then I remembered his body, the muscles moving across his back and arms as he washed himself vigorously, and I felt a little guilty; it had been different seeing him down there among a dozen other boys having their baths outside as I brushed my teeth, each person a feature of morning, now it seemed like a small violation.

I dance like a girl, I said into his ear.

He looked at me weird. You dance like a girl, and so? he said, squeezed his face thoughtfully. Standing up, he held out his hand. What, I said, confused and a little excited, and he said, Trust me, smiling a playful-wicked smile. He led me to the middle of the room where he started swaying his shoulders. God, Kayode, I said, covering my face with my hands. Love me, love me, love me, the speakers boomed, and he sang along, holding out his hands toward me, so ma fi mi si le / Oh I like it here.

A girl laughed, yelled, Dance!

Dance, someone else responded, and soon it was a chant, Dance! Dance! Dance!

You see? Kayode said, taking my hands and twirling me round. God, kill me now, I thought, and moved my hips. Yes, people cheered, and if not for these shouts of affirmation, I might have collapsed from the exposure. Closing my eyes, I let the music take hold of my body, waves of pleasure rippling through me. This was what people meant when they said dancing was fun, I thought, this absolute surrender. When the music stopped, I opened my eyes, and there was Kayode beaming, Ekene cheering, the dance floor drowned by laughter and applause. I shook Kayode’s hand and he pulled me into a manly hug, our shoulders clashing.

I need some air, I said, as the next song began.

God, me too, he said.

He followed me to the balcony, where a few people had carved a space for themselves to smoke and talk. The street below was dark, electric poles watching over the closed shops, and there was some breeze, and the music blasting inside was muffled, Kayode having shut the door behind us. I took a dramatic breath, saying how good the air was on my face. I felt happy yet anxious and exposed, a confusing meld: I’d noticed a few guys leave when Kayode led me to the dance floor, now I was sure that they’d left in disgust and anger, those had to be the only reasons.

I have to go home, I said.

He looked puzzled, concerned. Are you okay?

Yes, I said. I’m just not a party person. I’m exhausted already, but I’m glad you made me dance.

From the opening of “What the Singers Say About Love” from God’s Children Are Little Broken Things by Arinze Ifeakandu. Courtesy of A Public Space Books.