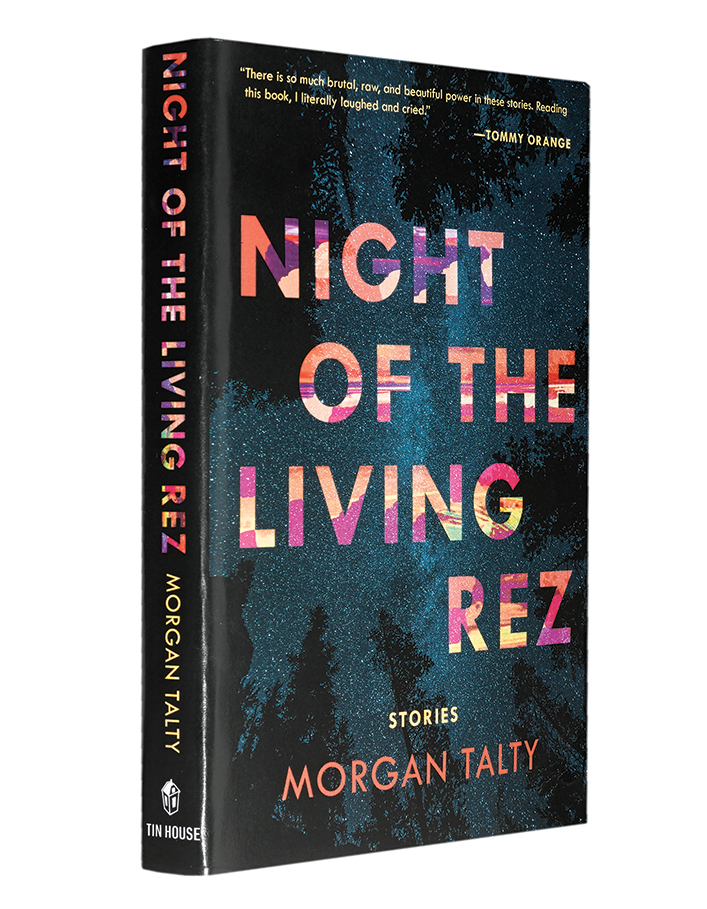

Morgan Talty, whose debut story collection, Night of the Living Rez, will be published in July by Tin House, introduced by Brandon Hobson, author of four books, most recently the novel The Removed, published by Ecco in 2021. (Credit: Talty: Tin House)

![]()

Morgan Talty’s debut collection of short stories, Night of the Living Rez, is a biting exploration of life on the Penobscot reservation. My admiration for the book wholeheartedly subscribes to the spirit of visibility and uniqueness as we’re seeing more Indigenous writers and books enter the mainstream cultural consciousness.

The aesthetic significance of these stories—which is to say, Talty’s technique, spare style, and intermingling of themes and variations of the wounded and difficult lives of his Penobscot characters—serves as an important glimpse into the landscape of literary fiction involving a resilient Indigenous people. I found myself moved by their lives and how well Talty is able to capture a wide range of emotions. While the stories are tragic, sad, and at times even humorous, they are perhaps best described by the title of the final story, “The Name Means Thunder.” Their unpredictability, like a thunderstorm, is what makes them extraordinary.

One of the things I love about this collection is the way you balance humor with sadness, which is difficult to do well. Can you talk a little about the importance of sadness and humor in the book and how you approach the process of finding that balance?

I write a lot about difficult and painful issues—violence, addiction, poverty—and too much of something can be hard to handle. That’s where humor comes in. I’ve heard someone say before that if you can make someone laugh, they’ll follow you anywhere. In my work, humor is partly about easing the pain that readers may feel for these characters, but it’s also, I think, sort of in my DNA. There’s a lot in this book that is personal, and humor was a big part of my coping with the difficulties my family and I experienced.

When it comes to finding that right balance between sadness and humor, I approach writing scenes and situations as I think any human being would. “If I were in this character’s shoes,” I’d ask, “would this moment be funny? When would I laugh about it?” That’s the best I can do when it comes to finding that balance—humor is so subjective, and it can be hard to anticipate what someone will find funny, whereas it’s a bit easier to anticipate what someone will find sad. At an event, I recently read “Burn,” which is the opener of my story collection, and at the end, members of the audience asked questions or shared thoughts. One person said, “Wow, I never realized how funny this was until I heard you read it.” And in my head, I’m like, “Who wouldn’t think some of this was funny!?”

Can you talk about how important it is for you in your work to provide a Penobscot person’s experience to visibly enter the mainstream cultural consciousness, and how Native literature is evolving and expanding in general?

Part of being Indigenous, I think, is this strange dichotomy of simultaneously being invisible and visible, which is a product of colonialism, the white man’s image of the “Indian,” and a deep Western desire to homogenize all Native folks, for who knows what reason. Simplicity? Assimilation? Mass genocide? Every Native person has a story about something dumb somebody said about them: “Oh, you’re Indian? You must be loaded from your casino!” That’s one thing someone said to me. The point here, though, is that this type of limited knowledge is so dangerous. Having a single story of someone—of a group—diminishes what is real about them. It dehumanizes them. It’s those multiple and many stories about various peoples—Indigenous tribes in this instance—that extend, and complicate, our understanding of what people think about Native Americans. To have Penobscot characters visibly enter into the mainstream cultural consciousness—written by one Penobscot person—is so, so important in making us visible on our terms. Native literature is evolving in this way: So many more Native writers are producing works from tribes that haven’t been represented in mainstream literature, and I really think non-Native readers want that. I also think that Native literature is also becoming just “literature”—that people are reading it for the story rather than a touch of the exotic, and this has a lot to do with Native writers avoiding that type of writing. We just have to keep pushing our stories as we see them.

Yes, and we’re seeing a sort of renaissance of Native literature and younger Native writers. What does that mean to you and for the state of literature in general? Along those lines, who are some of the writers who have influenced you and informed your work and this book specifically?

It means a great deal to me to be part of this new generation of Indigenous writers. We’re all contributing work that I believe is really pushing back against the archetypal images and hackneyed tropes out there about Native peoples, particularly in popular culture. What’s more, there seems to be a surge in the plethora of tribes being represented in fiction. I feel like if you asked a non-Native person to name five tribes, they would give you the major ones that have been in popular culture forever and perhaps some local tribes from their area. And so with that, right now, it’s not just those familiar tribes that are being written about, but other tribes, like my own—the Penobscot—that are being seen, that readers are learning about not as a subject of study, but as a subject of shared humanity.

So many writers have influenced me and informed my work. I already know I’m going to leave people out. Louise Erdrich, N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Thomas King, Vine Deloria Jr., Joy Harjo, Linda Hogan, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Paula Gunn Allen. More contemporary Native writers include Tommy Orange, Terese Marie Mailhot, Richard Van Camp, Eden Robinson, Dawn Dumont, Margaret Verble, Kelli Jo Ford, Toni Jensen, David Treuer, Stephen Graham Jones, and you! Other writers who aren’t Native who have really influenced my work include Anton Chekhov, Raymond Carver, Denis Johnson, Anthony Doerr, Jennifer Egan, Alice Munro, Edwidge Danticat, Jamel Brinkley, Toni Morrison, and Isabel Allende.

Copyright © 2022 by Morgan Talty. Audio excerpt courtesy of Recorded Books, Inc. Recorded by arrangement with Tin House Books. Read by Darrell Dennis.

An excerpt from “Earth, Speak” from Night of the Living Rez by Morgan Talty

“We have to do it tonight,” Fellis said.

“With no code?”

“And then we’re out of here.”

I counted my fingers. “We got no money, your truck’s a piece of shit, the next arts festival ain’t till October, and we haven’t weaned off our doses.”

“We got money.”

“Yeah, okay,” I said. “You bummed twenty yesterday from your mom.”

Fellis stood. “I’ve been bumming from my mom for thirty-one years.” He pulled the bed away from the wall. In the corner, he peeled back the carpet and picked up three envelopes from the cold wooden floor. He emptied all three on the shifted bed.

All these late boring nights we didn’t do anything because he was broke!

“Twenty-eight hundred bucks,” Fellis said.

I knelt in front of the bed and felt the money, some bills soft like velvet, others stiff and fresh.

“I got money,” he said.

“Your truck’s still a piece of shit.”

Fellis took the money from my hands. “You don’t want to do it, do you?”

I said nothing. The whole thing was my idea. We’d been watching Antiques Roadshow one long boring moon-night last week and some old dusty lady brought in an old root club that was worth five grand. Five grand! I said, “Fellis, the museum has tons of those!” and we looked at each other and got off the couch and walked fast to the head of the Island, right near the bridge. We went out back of the little museum whose only visitors were white people wanting pictures. Looking through the window, Fellis had seen the alarm box blinking green.

“Do you or don’t you?” Fellis said.

“What about our doses? I ain’t getting sick if we’re on the road.”

Fellis waved the envelopes at me. “You got Tabitha’s number?”

“I’m not drinking puked-up methadone,” I said.

“She don’t puke it up,” Fellis said. “You’re retarded if you think that.”

“I’ve seen her do it,” I said, even though I hadn’t.

“You’re full of shit,” Fellis said. “She gets full take-homes. You think that lockbox is her purse?”

“Even if she sells to us,” I said, “where are we going?”

“Down south to sell it all.”

“Why don’t we just learn how to make our own root clubs or baskets and sell them?”

Fellis stuffed the rest of the bills into the envelopes and put them back under the carpet. He straightened the bed.

“I ain’t got time for that,” Fellis said. “I’m doing it my way.”

From Night of the Living Rez: Stories by Morgan Talty. Published with permission of Tin House. “Earth, Speak” first appeared in Shenandoah. Copyright © 2022 by Morgan Talty.