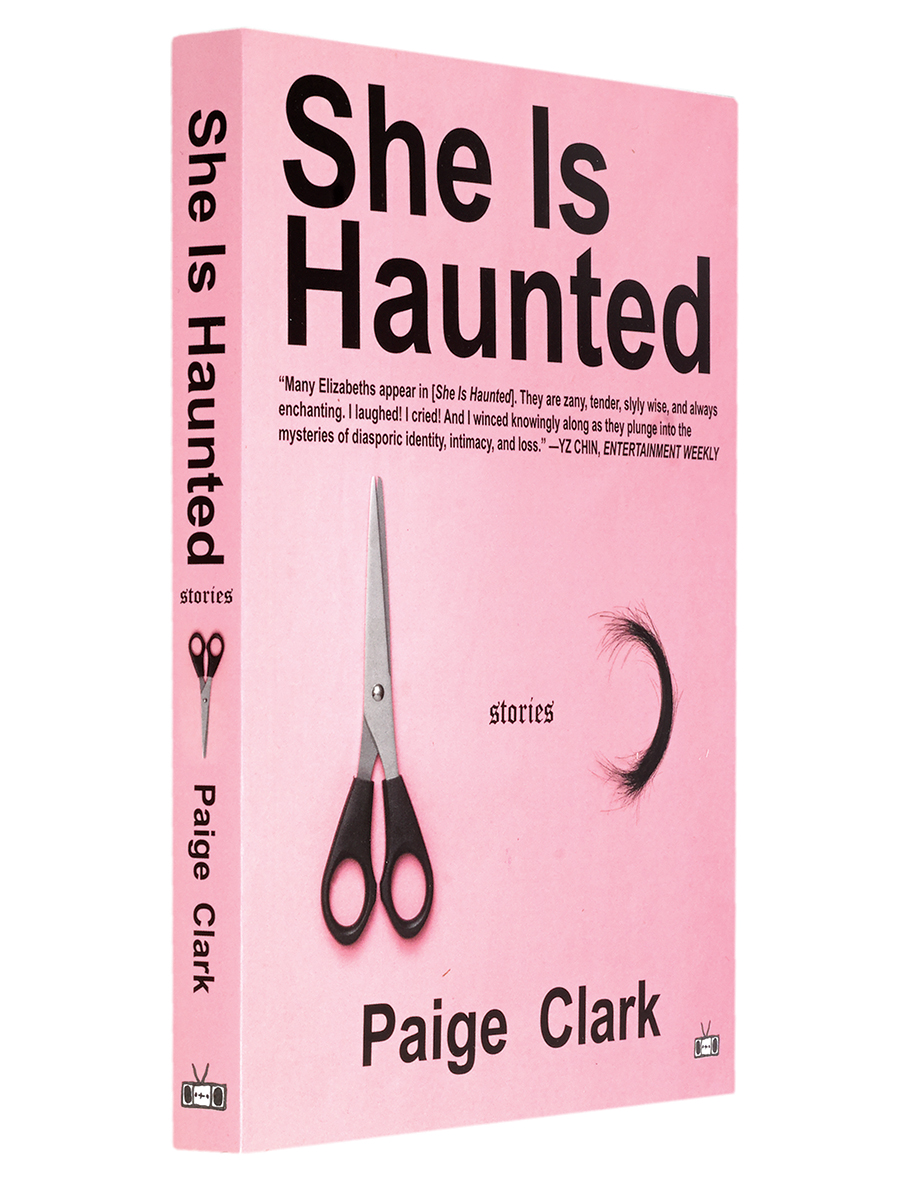

Paige Clark, whose debut story collection, She Is Haunted, was published in May by Two Dollar Radio, introduced by YZ Chin, author of two books, most recently Edge Case, published by Ecco in 2021. (Credit: Clark: Marcelle B. Radbeer; Chin: Drew Stevens)

![]()

When I read Paige Clark’s She Is Haunted, I was by turns delighted and moved: delighted because Clark takes obvious care and joy in crafting her sentences, and moved because her stories approach life’s mysteries with such emotional honesty. Many different Elizabeths appear throughout the stories in the collection. In “Times I’ve Wanted to Be You,” a widow named Beth wears her husband’s clothes, wishing to turn into him. In the freewheeling sci-fi “Amygdala,” an Eliza has her left frontal cortex removed to better survive climate change. These Elizabeths confront various versions of intimacy and loss, each making a devastating discovery about “[t]he whole charade that a woman could ever belong to herself.” While the characters often surprise, they are never quirky for quirky’s sake.

She Is Haunted was first published by Allen & Unwin, an independent press in Australia, where it was shortlisted for the 2021 Readings Prize for New Australian Fiction and longlisted for the 2022 Stella Prize. Clark lives in Melbourne, where she is working toward her PhD, studying the relationship between race, craft, and the teaching of creative writing. While reading Clark’s stories, published in a U.S. edition by Two Dollar Radio in May, I had the impression of stepping out from behind a screen of trees and approaching a cliff from which, if I looked carefully, I could discern the outline of my own home. In other words, reading her suffused me with the wonder of approaching my life from an unexpected angle, leaving me awestruck but also disturbed. It is a perspective art uniquely provides. We all need it, from time to time.

In your collection there is constant play and experimentation at the sentence level, even when the subject matter might sometimes be described as “heavy.” Was the writing process more often led by the art of the sentences or by the progression of the plot? Were you surprised by your stories?

I find writing such a demanding process, especially starting to write, that I’m not choosy about how I find my way into a story. Sometimes I will begin with just a premise, or sometimes I will have the whole plot mapped out scene by scene before I start. Sometimes I start with the first sentence, sometimes the last. There are times I have no idea where I am going and other times when I know exactly where I need to get. If the writing is not sentence-led, then I make sure that I pay close attention to the sentence in the revision process. I find the quicker, more plot-driven stories to write are a real bear to edit for this exact reason: I have to go in and fine-tune the language afterward. Whereas when I really listen to what the story should sound like and plod along, one sentence to the next, the revisions are easy—or easier. I surprise myself by writing in the first place or being able to finish a story at all; it still brings me such joy every time I complete anything. When writing is at its least painful, I am amusing myself with wordplay, though the worst of it gets weeded out by my very discerning writing group, thankfully.

It’s always wonderful to hear writers talk about joy in the writing process. How do you know when a story is done? Is joy the main sign, or does that come later?

Oh, joy! It does seem so elusive when you’re writing. I think for me elation is a sign that I am done with the writing process but not a sign that I am done. I usually buzz around the house and drive my partner and dog up the wall on the days I “finish” writing. I get my comeuppance when I sit back down at the desk for editing, though. All of the joy of the previous day drains out of me, and all I can see are the errors on the page. Editing is as much a part of my process as the writing itself. And perhaps because of this fixation with editing, I never see any of my work as complete. Whenever I return to a story—days later or months later—there’s always something I want to change. I can lose hours looking at something as simple as the versus a to introduce a noun. I can lose days reading and rereading the work aloud to myself, listening for what the story should be.

I find there’s an energetic restlessness in the collection, with its stories set in various cities and characters often acting in unexpected ways. What do you see as a thread running through the book?

I am a terribly impatient person, and I must have somehow transferred this energy into the work. I am always eager to resolve problems or figure out “why” something happened; I think this bleeds into each of my stories when I’m writing. I feel like I’m racing toward the finish line, toward the natural ending. I want that for my characters as much as I want that for myself. This resolution is often—usually—not the one the character had in mind. Life and stories about life resist neat packaging; it is perhaps this push to resolve unresolvable feelings and situations that leads to characters acting out in unexpected ways. As for setting, my stories follow me to whatever places I go to—even to the surreal, to the imaginary. If any restlessness unifies this collection, it’s my own.

What was it like to first publish the book in Australia, then a year later in America?

The book came out in Australia at the start of what would be months-long lockdowns for both Sydney and Melbourne in the second half of 2021. After a number of postponed book events and book launches, eventually everything either moved online or got canceled. These cancellations made it feel like the book never even came out. So having the book published in America was as exciting as if it were coming out for the first time. What I’ve learned about the publication process in both Australia and the United States is that everything that happens after the editorial process isn’t for you as the writer; it’s for the audience you might reach, for the readers. My job as a writer starts again when I sign off on the proofreading and the book goes to the printer. The publication of She Is Haunted is the terrifying beginning of whatever the next book may be.

Audio narrated by Kimie Tsukakoshi; the audio edition is published in North America by Blackstone Publishing.

An excerpt from the story “Private Eating” from She Is Haunted

Maybe if the man had not been an anesthesiologist, or if the bubbly wine at the restaurant had been opened the night before, or even if the man had showed up five minutes late, apologetic but breathless, careless in the way the woman hated the most, she wouldn’t have lied and said she was a vegetarian.

But he showed up on time and said, “I’m a vegetarian, are you?” Though this was not the first thing out of his mouth; he played the role of the handsome doctor initially.

“Yes,” she said. She thought of what she’d eaten that day, mostly vegetables and carbohydrates, and felt assured she wasn’t lying.

“Oh, thank god,” he said. “You won’t believe what I’ve seen meat do to people’s bodies.” The man cut into a gigantic field mushroom. His table manners were impeccable, the woman observed, even if he did eat with his fork in his right hand.

“I can imagine,” she said. And she could. She had spent hours thinking about the grotesque things that happened to other people’s bodies at the man’s place of work.

The rest of the evening passed without further discussion of bodily diseases and for that the woman was quietly grateful. The man chatted about the environmental impact of meat and the woman mostly agreed with him. Factory farming was bad. Cows made a lot of methane. In fact, she’d been trying to reduce her own footprint. She paid extra to the power company to offset her carbon emissions. She bought all of her clothes second-hand and did not drive a car. And, unlike most of the people she knew, she’d only purchased a single piece of furniture that was mass-produced and Swedish-designed.

Before they even ordered dessert— tiramispoons, individual portions of the Italian dessert served in a soup spoon— the woman was a convert. A vegetarian. Never mind her mother. Her darling po po. Never mind the whole of her extended carnivore family.

Over the course of the evening, the man talked about enough of the right things to prove to the woman he was sane. And wasn’t that in itself a rare treat? They both had no taste for sport. They’d enjoyed a few of the same novels. One of the man’s pupils was slightly larger than the other, which made him appear constantly surprised. Had she mentioned that he was a doctor?

By the time he paid the bill— he insisted— and said, “My last relationship ended when my girlfriend ate a steak in front of me,” the woman had consumed too many glasses of wine to want anything else than for him to take her home.

Outside, it was raining lightly. Under the awning of the restaurant, they made a charade of ordering rides to go their separate ways. The woman pressed up against the man, knowing full well what would happen next, picturing his pointy tongue in her mouth. She thought of the whole parade of dishes she could prepare with baby carrots, legumes and soy products, foods she knew all vegetarians liked.

But when the ride arrived, the man gave the woman a kiss on the lips and a squeeze, and put her in the car.

He said, “I’m sorry. I like to go slow.”

As her car sped off, she looked back at the man, who gave her a small wave before he was out of sight. Visions of miniature vegetables danced in the woman’s head.

The woman got home to the apartment she once shared with a boyfriend, though he’d not lived there for a long time now. They didn’t break up because of a cut of beef, but because the boyfriend’s parents did not approve of the woman. In his defense, for many years he’d trusted his parents would come around. During the last fight they had, the boyfriend said he wanted to raise their future children as Christians. The woman was an atheist— an agnostic at best. She never said anything condescending about people who were believers. But she knew what her boyfriend meant. He would not marry a Chinese woman. His parents had won. The entire time they dated, the woman’s boyfriend had not been to church once.

The woman sat down in front of the television with a bag of marshmallows. This was what her friend Cisco called “private eating.” She switched between the two food channels she watched exclusively. Tonight, on a farm-to-table program, a chef turned farmer slaughtered his pet goat to make dinner. He cried when the goat was shot in front of him at the humane abattoir, then turned the goat’s hide into a rug for his dog and the goat’s brains into a stew. The woman ate the entire bag of marshmallows before she realized her mistake. She’d forgotten her puffed treat was made from horses’ hooves. She would try again to be a vegetarian tomorrow.

From She Is Haunted. Copyright © 2022 by Paige Clark. Excerpt by permission of Two Dollar Radio.