Jill Kalotay has been supporting the Spencertown Academy Arts Center as a volunteer for the past ten years. In 2015 she accepted the position of cochair of the Festival of Books with David Highfill, an executive editor at William Morrow, and she joined the Spencertown Academy Board of Directors in 2016.

It is important to me to support the arts, and particularly authors, since my daughter Daphne announced at the age of three that she wanted to be a writer. She has shown me what hard work it is, and how steep the climb to success is in today’s market. The annual Festival of Books, presented by the Spencertown Academy Arts Center, is a way to feature writers and focus on books—and to help ensure that they will be here for some time to come.

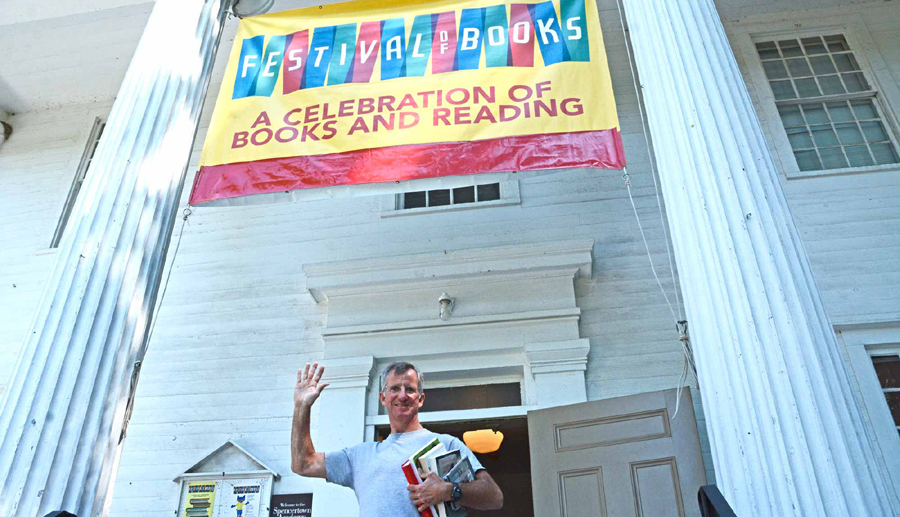

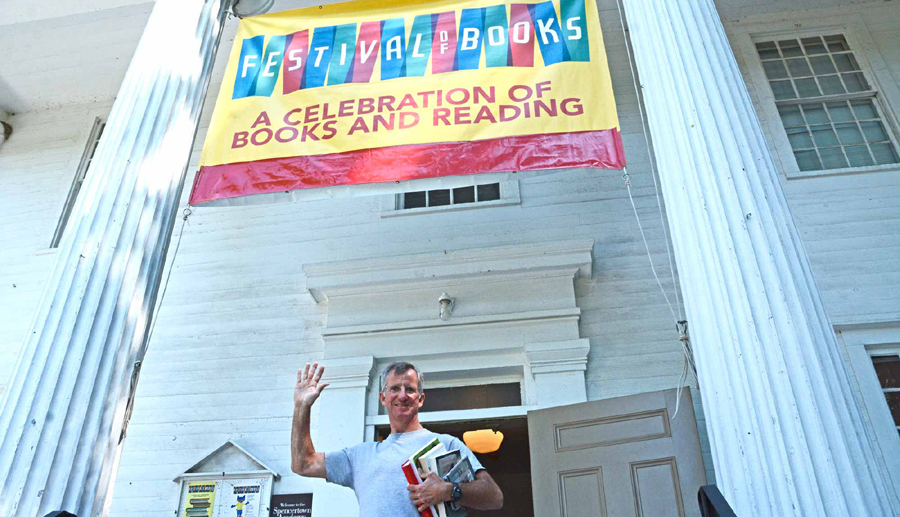

Housed in a beautifully restored 1840s Greek Revival schoolhouse at 790 State Route 203 in Spencertown, New York, the Spencertown Academy Arts Center is a cultural center serving Columbia County, the Berkshires, and the Capital region. It offers a variety of free and low-cost community arts events, including concerts, readings, theater pieces, art exhibitions, and arts-related workshops and classes.

For the past twelve years, the Festival of Books has been a major fund-raising event for the Spencertown Academy Arts Center. Subtitled “All Things Literary,” the festival provides a stage for authors to talk about their new books, poets to read from their collections, and high school students to read their prizewinning short stories and essays, entered earlier in a contest we sponsor in conjunction with the festival. (You can read the winning entries here.)

The three-day event takes place over Labor Day weekend, and also features a huge book sale, with over ten thousand donated books on offer. “The best books sale in the area,” according to many visitors. All the books are culled, cleaned, and sorted by Academy volunteers—those book lovers who want to get as many books as possible out into the world and bring in money for the Academy so that we can keep our doors open for one more year. Typically all of the authors come without promise of remuneration.

This year, we hosted an amazing array of artists, and five fiction writers were generously supported by grants from the Poets & Writers’ Readings & Workshops program.

Wesley Brown read from his Dance of the Infidels, a collection of related stories about jazz musicians (mostly real) and jazz lovers (imagined) in 1930s and 1940s New York City jazz clubs.

Rebecca Morgan Frank read from her collection, The Spokes of Venus, and spoke about the inspiration for her poems, in which magicians, wig makers, sculptors, perfumers, and choreographers help conjure these works about making and observing art.

In spite of the incessant rain beating on our tent, on one of the worst days of the summer, Elinor Lipman and Louie Cronin shared the stage for a session called “If These Walls Could Talk.” Lipman’s latest book, On Turpentine Lane, is a romantic comedy about a restless woman who impulsively buys a dilapidated house that soon reveals a mysterious past. Everyone Loves You Back, Cronin’s very funny first novel, features another house in dire need of repair, this one in Cambridge. Town and gown meet again!

Patricia Park read from her novel, Re Jane, set in the disparate worlds of Queens, Brooklyn, and Seoul during the early 2000s. In the novel, Jane Re, a Korean American woman (and orphan), lives with her aunt and uncle in Queens, and feels like an outsider. Park’s animated talk provided glimpses of her own background in Flushing, Queens and described some of the difficulties in getting her novel onto the TV screen. Actor and producer Daniel Dae Kim is adapting the book as a half-hour comedy series.

For the past five years we have been operating as an all-volunteer organization. We rely totally on all the volunteers, donors, sponsors, and kind artists who support us with their valuable time and talents. We are so grateful! And especially thankful to Poets & Writers for their financial backing of writers and events such as ours.

Support for the Readings & Workshops Program in New York is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, with additional support from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Photo: Spencertown Academy Arts Center’s Festival of Books (Credit: Peter Blandori).