DéLana R.A. Dameron is the author of Weary Kingdom (University of South Carolina Press, 2017), which is part of the University of South Carolina Press’s Palmetto Poetry Series, edited by Nikky Finney. Her debut collection, How God Ends Us (University of South Carolina Press, 2009), was selected by Elizabeth Alexander for the 2008 South Carolina Poetry Book Prize. Dameron holds an MFA in poetry from New York University where she was a Goldwater Hospital Writing Workshop Fellow. She has conducted readings, workshops, and lectures all across the United States, Central America, and Europe.

I have been an alumna of the Cave Canem summer retreat since 2008, and had the opportunity to participate in smaller New York City workshops in 2008 and 2009. While the summer retreat is life-changing and affirming, and provided me with a long roster of lifelong friends in the poetry world, the prolonged space(s) with Myronn Hardy and Tracy K. Smith as facilitators provided me with a framework of what a community workshop could look like, how to be rigorous readers and writers in an after-work, weekly setting, while also building community. Cave Canem, for me, is about building a community of people who will sharpen your poeming pen.

I have been an alumna of the Cave Canem summer retreat since 2008, and had the opportunity to participate in smaller New York City workshops in 2008 and 2009. While the summer retreat is life-changing and affirming, and provided me with a long roster of lifelong friends in the poetry world, the prolonged space(s) with Myronn Hardy and Tracy K. Smith as facilitators provided me with a framework of what a community workshop could look like, how to be rigorous readers and writers in an after-work, weekly setting, while also building community. Cave Canem, for me, is about building a community of people who will sharpen your poeming pen.

I did all of this before I entered an “official” MFA workshop table at New York University. I say that to say, when I exited the MFA workshop table, I did not choose a life of teaching poetry in academia (though I would love to teach a class here or there!), but found other ways to pay my bills, and searched for opportunities to teach workshops to folks who went to work from 9:00 AM until 6:00 PM and came and sat down and still endeavored to read and write poetry in a supportive and educational space.

When Cave Canem asked me to teach the Poetry Conversations workshop, billed especially for beginning and intermediate poets, I jumped at the opportunity and said yes. Here, I was able to come home, to open up space for the many levels of poets that would hopefully sign up for the course.

It became very clear to me that I wanted to teach what I live: writing the everyday/the landscape(s) I inhabit into poetry, making it sing.

The “A Street in Brooklyn: Writing Into the Urban Landscape” workshop was at once a survey of Gwendolyn Brooks’s work as a poet. Weekly we read chronological selections from A Street in Bronzeville (Harper, 1945), Annie Allen (Harper, 1949), The Bean Eaters (Harper, 1960), In the Mecca (Harper, 1968), and single poems from her collected works in Blacks (David Co., 1987).

Of her own work and inspiration, Brooks said: “I wrote about what I saw and heard in the street. I lived in a small second-floor apartment at the corner, and I could look first on one side and then the other. There was my material.”

Reading Brooks is not only an exercise in understanding the mastery of writing the ordinary (Black folks in Chicago, the urban landscape writ large, etc.) into extraordinary poetry, but quickly I found that to teach Brooks over the span of her career, as documented in Blacks, is to also teach a Black history course, a Chicago history course.

Then, to charge the poets to do as Brooks did, and look out of their own windows for the poetry of their everyday lives, they included their own poetic historical markers of where and who they are now, especially in the context of gentrification, “urban renewal,” and the general displacement of Black cultural markers, people, histories, and stories.

At the last class there was an overwhelming sadness, but also a triumph. We had been through a literal journey together. At my urging, I asked poets to write about their neighborhood, a place that no longer existed, a place that showed NYC Black History—a mural, a statue, a hanging tree—and to write those things into sonnets, in rhyme, as ballads, as Brooks did in her early years. Together we coined the term “Brooksonian” and looked for moments when she shined the best, and then applied it to our poems that we brought to the table for workshop.

As the weeks progressed, and we marched along the historical timeline from 1945 (A Street in Bronzeville) to 1968 (In the Mecca) and beyond, we watched Brooks’s work open up, and we talked about what it meant to be a poet moved by a historic moment, and what it meant for Brooks to break open, even more, the poetic form. We talked about the uses of poetry, the politics of it, the immediacy and need. That same day a participant brought in a poem that referenced, as Brooks might have (and did for her Chicago Black people), Eleanor Bumpers, who was shot and killed by police in 1984 in the Bronx, as well as the now no longer existing Slave #1 Theater in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and all I could do was shake my head in awe: We had arrived.

Support for the Readings & Workshops Program in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Frances Abbey Endowment, the Cowles Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

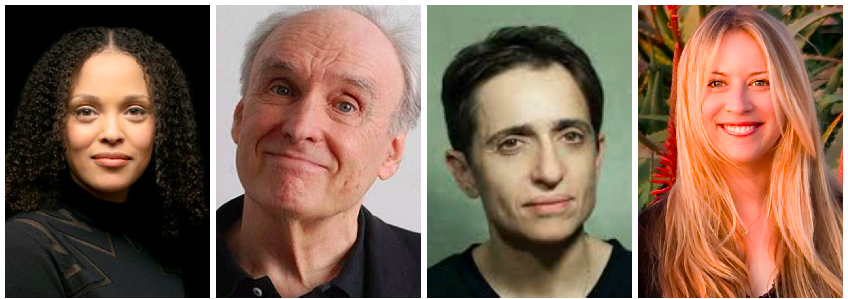

Photo: (top) DéLana R.A. Dameron (Credit: Rachel Eliza Griffiths). (bottom) Workshop participants (Credit: DéLana R.A. Dameron).

I have been an alumna of the Cave Canem summer retreat since 2008, and had the opportunity to participate in smaller New York City workshops in 2008 and 2009. While the summer retreat is life-changing and affirming, and provided me with a long roster of lifelong friends in the poetry world, the prolonged space(s) with Myronn Hardy and Tracy K. Smith as facilitators provided me with a framework of what a community workshop could look like, how to be rigorous readers and writers in an after-work, weekly setting, while also building community. Cave Canem, for me, is about building a community of people who will sharpen your poeming pen.

I have been an alumna of the Cave Canem summer retreat since 2008, and had the opportunity to participate in smaller New York City workshops in 2008 and 2009. While the summer retreat is life-changing and affirming, and provided me with a long roster of lifelong friends in the poetry world, the prolonged space(s) with Myronn Hardy and Tracy K. Smith as facilitators provided me with a framework of what a community workshop could look like, how to be rigorous readers and writers in an after-work, weekly setting, while also building community. Cave Canem, for me, is about building a community of people who will sharpen your poeming pen.