5 Over 50 Reads 2016

Read excerpts of the debut books by 2016’s 5 Over 50: Desiree Cooper, Sawnie Morris, Paul Vidich, Paula Whyman, and Paul Hertneky.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

Read excerpts of the debut books by 2016’s 5 Over 50: Desiree Cooper, Sawnie Morris, Paul Vidich, Paula Whyman, and Paul Hertneky.

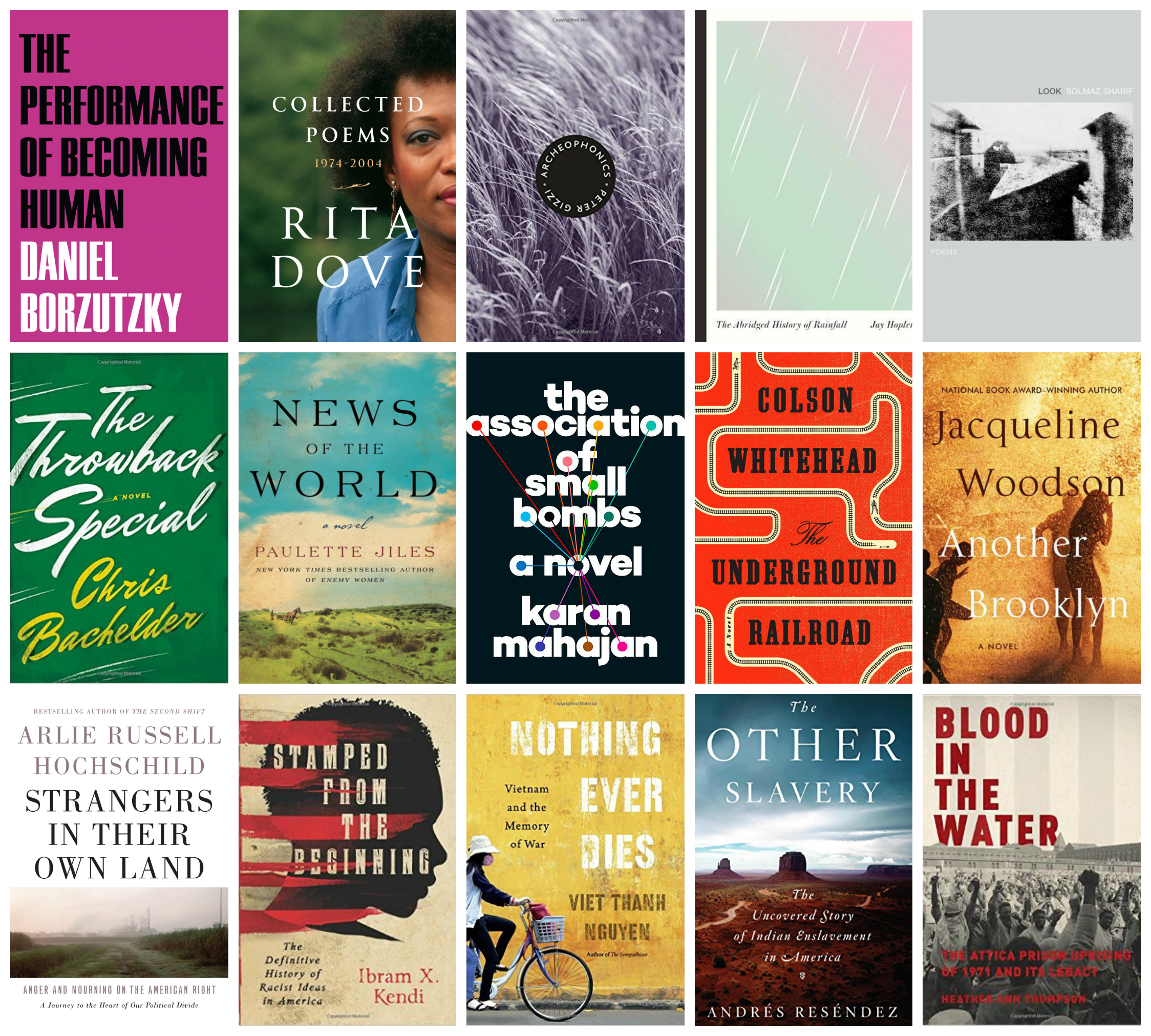

The National Book Foundation has announced the finalists for the 2016 National Book Awards. The annual prizes are given for books of poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and young people’s literature published in the previous year. The winners receive $10,000; each finalist receives $1,000. The winners will be announced on November 16 at an awards ceremony in New York City.

The finalists in poetry are:

Daniel Borzutzky, The Performance of Becoming Human (Brooklyn Arts Press)

Rita Dove, Collected Poems 1974–2004 (Norton)

Peter Gizzi, Archeophonics (Wesleyan University Press)

Jay Hopler, The Abridged History of Rainfall (McSweeney’s)

Solmaz Sharif, Look (Graywolf Press)

Mark Bibbins, Jericho Brown, Katie Ford, Joy Harjo, and Tree Swenson judged.

The finalists in fiction are:

Chris Bachelder, The Throwback Special (Norton)

Paulette Jiles, News of the World (William Morrow)

Karan Mahajan, The Association of Small Bombs (Viking)

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad (Doubleday)

Jacqueline Woodson, Another Brooklyn (Amistad)

James English, Karen Joy Fowler, T. Geronimo Johnson, Julie Otsuka, and Jesmyn Ward judged.

The finalists in nonfiction are:

Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (The New Press)

Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (Nation Books)

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (Harvard University Press)

Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy (Pantheon Books)

Cynthia Barnett, Masha Gessen, Greg Grandin, and Ronald Rosbottom judged.

The longlists for the awards were announced in September. Established in 1950, the National Book Awards are among the literary world’s most prestigious prizes. The 2015 winners were Robin Coste Lewis in poetry for Voyage of the Sable Venus (Knopf), Adam Johnson in fiction for Fortune Smiles (Random House), and Ta-Nehisi Coates in nonfiction for Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau).

The New York Public Library's newly renovated reading room now includes a book train, an adorable and technologically impressive book delivery system with cars running over a total of 950 feet of horizontal and vertical track, which provides an efficient and enjoyable experience for staffers and visitors.

This past weekend, the New York Review of Books published an exposé in an attempt to uncover the true identity of the Italian novelist Elena Ferrante, provoking anger and criticism from those in support of the writer’s wish to remain anonymous. Have you ever wished for anonymity, or do you imagine that you might in the future? Drawing examples from your own experiences with writing and private versus public life, write a personal essay about the issues at stake in this situation, such as celebrity authors, sexism, and the changing relationship in contemporary culture between artist and audience.

In this video, Benjamin Percy, author of Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction (Graywolf Press, 2016), is challenged to tell a five-minute true story from a randomly selected prompt for the Back Fence PDX storytelling series. Percy joins the two-day Poets & Writers Live conference in San Francisco on January 14 and 15, 2017.

Teju Cole reads from his novel Open City (Random House, 2012) while accepting the 2015 Windham Campbell Prize for Fiction. Cole speaks about his collection of essays, Known and Strange Things (Random House, 2016), in the September/October issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.

Banned Books Week is an annual celebration led by a coalition of diverse organizations and foundations to encourage awareness of book censorship and recognize the freedom to read. Browse through the American Library Association’s lists of top banned books—organized by decade, classic titles, young adult authors, and more—and select a book you’ve read that strongly resonates with you. Write an essay that examines your response to the censorship or challenging of this book, drawing on your own memories of reading it and exploring the idea of an appropriate audience for this literature.

This morning, the MacArthur Foundation announced the twenty-three recipients of its 2016 fellowships. Also known as “Genius Grants,” the annual fellowships of $625,000 each—which are distributed to recipients over a period of five years—are given to individuals who “have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity of self-direction.”

Five writers received fellowships this year, including poet Claudia Rankine, creative nonfiction writer Maggie Nelson, journalist Sarah Stillman, graphic novelist Gene Luen Yang, and playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins.

The author of five books, Claudia Rankine is “a poet illuminating the emotional and psychic tensions that mark the experiences of many living in twenty-first-century America,” the announcement stated. Her award-winning 2014 collection, Citizen: An American Lyric, interrogates racially charged violence through poetry, documentary prose, and images to “convey the heavy toll that the accumulation of these day-to-day encounters exact on black Americans.”

Maggie Nelson has written five books of creative nonfiction, including The Red Parts (2007), Bluets (2009), The Art of Cruelty (2011), and The Argonauts (2015), as well as several poetry collections. The MacArthur Foundation writes that Nelson is “forging a new mode of nonfiction that transcends the divide between the personal and the intellectual and renders pressing issues of our time into portraits of day-to-day lived experience.”

Now in its thirty-fifth year, the MacArthur Fellows Program encourages exceptional individuals across a broad range of fields to pursue their creative, intellectual, and professional projects. Fellows are recommended by external nominations, and then chosen by an anonymous selection committee; there is no application process. Between twenty and thirty fellows are selected each year.

For a complete list of this year’s recipients and more details about the fellowships, visit the MacArthur Foundation website.

(Photos from left: Claudia Rankine, Maggie Nelson)

“I think if you say that art and politics, or religion and politics, mustn’t mix, don’t mix, that is itself a political statement,” novelist Mohsin Hamid said in an interview in the Financial Times in 2011. While there are many writers who choose not to overtly link their creative work to politics, there is also a long history of political art: work that engages with patriotism or protest by poets such as W. H. Auden, Adrienne Rich, Wole Soyinka, and Walt Whitman. Do politics ever figure into your own creative writing? Why or why not? In this presidential-election season, whether you are engaged and informed by politics or try to avoid the topic altogether, take a moment to examine the history of your personal relationship with politics. Write an essay that explores how your interest in or aversion to the topic might have been affected by your childhood upbringing and environment—family, friends, or local groups and organizations—and the reasons behind your choice to either integrate or separate politics from your creative work.

Sarah Rafael García is the current artist-in-residence at the Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, California. As part of her residency, García is creating the LibroMobile, a bookmobile that integrates literature, visual exhibits, year-round creative workshops, and live readings. In addition, García is the author of Las Niñas: A Collection of Childhood Memories (Floricanto Press, 2008), coeditor of the anthology pariahs, writing from outside the margins, founder of the reading and writing youth empowerment program Barrio Writers, and a 2016 Macondista. Below, she blogs about the mission of LibroMobile, as well as recent and upcoming P&W–supported events.

LibroMobile, a project of Red Salmon Arts in Santa Ana, California, is a bookmobile designed to cultivate diversity by offering affordable books by writers of color; bilingual and Spanish books for children, youth, and adults; as well as books that speak to culture and social justice issues relevant to the local community. LibroMobile also includes a community board to post local resources and a traveling Little Free Library—a book exchange for those who cannot afford to buy a book off the bookmobile.

LibroMobile, a project of Red Salmon Arts in Santa Ana, California, is a bookmobile designed to cultivate diversity by offering affordable books by writers of color; bilingual and Spanish books for children, youth, and adults; as well as books that speak to culture and social justice issues relevant to the local community. LibroMobile also includes a community board to post local resources and a traveling Little Free Library—a book exchange for those who cannot afford to buy a book off the bookmobile.

The design of the LibroMobile is reminiscent of the iconic paletero carts or fruit vendors that are part of Downtown Santa Ana. LibroMobile’s literary events and creative writing workshops provide Santa Ana residents of all ages opportunities to meet award-winning writers of color, and to write, revise, and submit their own work for possible publication.

This past month, with the help of Poets & Writers’ Readings & Workshops program, LibroMobile launched its inaugural exhibit and literary event, Macondistas en SanTana, featuring Macondo Writers’ Workshop attendees (known as Macondistas) Reyna Grande and Emmy Pérez. Pérez led a free workshop for participants sixteen years old and older and was later joined by Grande, where both performed alongside the AntenaMóvil, a literary project whose designers helped in the conceptualization of the LibroMobile.

The LibroMobile resides at Grand Central Art Center (GCAC) and travels throughout Santa Ana visiting a variety of communities, including Alta Baja Market at Calle Cuatro and the monthly Artwalk in the Artist’s Village, doing its work to build community and promote literacy. Upcoming events include: A Bilingual Children’s Reading Hour with authors René Colato Laínez and Amy Costales on September 24, and Poetry of Resistance: A Tribute to Francisco X. Alarcón, a free P&W–supported workshop and reading with Javier Pinzón and Odilia Galván Rodríguez on October 27.

The LibroMobile resides at Grand Central Art Center (GCAC) and travels throughout Santa Ana visiting a variety of communities, including Alta Baja Market at Calle Cuatro and the monthly Artwalk in the Artist’s Village, doing its work to build community and promote literacy. Upcoming events include: A Bilingual Children’s Reading Hour with authors René Colato Laínez and Amy Costales on September 24, and Poetry of Resistance: A Tribute to Francisco X. Alarcón, a free P&W–supported workshop and reading with Javier Pinzón and Odilia Galván Rodríguez on October 27.

LibroMobile is indebted to Poets & Writers, Red Salmon Arts, the GCAC, and the City of Santa Ana’s Investing in the Artist Grant Opportunity for empowering this project to provide diverse books and host marginalized literary voices that can effectively support, inspire, and challenge our Santa Ana residents to read, write, and build community.

For more information about LibroMobile and upcoming events, visit the Facebook page and website.

Photo 1: Sarah Rafael Garcia. Photo 2: Workshop participants.

Major support for Readings & Workshops in California is provided by the James Irvine Foundation and the Hearst Foundations. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.