Poetry and Standardized Tests, the Shakespeare Detective, and More

Fiction writer Yaa Gyasi on her debut novel; new Philip Levine poetry books; a survey of Great American Novels; and other news.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

Fiction writer Yaa Gyasi on her debut novel; new Philip Levine poetry books; a survey of Great American Novels; and other news.

Nelson Doubleday Jr. Collection to go to auction next week; Florida librarians create fake borrowers to save books; Powell’s Books sends titles to Obama and Trump; and other news.

Jennifer Patterson is a grief worker who uses words, threads, and plants to explore survivorhood, body(ies) and healing. She is the editor of Queering Sexual Violence: Radical Voices From Within the Anti-Violence Movement (Riverdale Avenue Books, 2016), facilitates trauma-focused writing and embroidery workshops, and has had writing published in places like OCHO: A Journal of Queer Arts, the Establishment, HandJob, and the Feminist Wire. She is also the creative nonfiction editor of Hematopoiesis Press, which has their first issue out this month. A queer and trans affirming, trauma-informed herbalist, Patterson offers sliding scale care as a practitioner with the Breathe Network as well as through her own practice Corpus Ritual Apothecary. Recently, she finished a graduate program with a thesis focused on translating embodied traumatic experience through somatic practices and critical and creative nonfiction. You can find out more at ofthebody.net.

What makes your workshops unique?

The workshops I offer are multi-dimensional. They’re grounded in writing through, with and about trauma (however people define that for themselves), and in reading other people’s writing about trauma and violence. There’s a somatic approach so we attend to the wisdom in our bodies that we sometimes forget, which might look like lying on the ground and breathing deeply. We hold space for each other in a way that feels really loving, expansive, and honestly, these days, it feels necessary and transformative. I’ve offered them in LGBTQ centers, at harm reduction clinics, in veterans hospitals, and universities. We’re living in a burning world and a lot of us have always felt that singe so it helps to unpack it on the page and turn it into something. I mean, trauma is always on the page but centering it in this way, I think, gives people permission to do the work they have been wanting and needing to do.

What techniques do you employ to help shy writers open up?

First, I thank people for showing up. Showing up is the hardest part especially when you’re inviting people to show up and write about their hardest experiences. I try to let go of demands and expectations and I let people know that they never have to share out loud if they don’t want to. (And actually, more times than not, most, if not all people share out loud.) We build a shared altar. I bring a freshly brewed herbal tea to calm nervousness and support the heart. I remind everyone that wherever they are and whatever comes out of the pen, for that moment, is just right. There’s plenty of time for editing—these workshops are for digging inside and generating.

What has been your most rewarding experience as a teacher?

Mostly just hearing from people that they felt more connected to their writing practice and, in turn, to themselves. That they feel heard and understood. That they felt something in their body soften or move around just a little.

What affect has this work had on your life and/or your art?

I recently finished a thesis (and soon to be manuscript) on trauma, somatic writing and embroidery—using stitch as a metaphor for making and remaking the wound—and it was incredibly difficult work so I’ve been taking a little breather. Some weeks the only time I write is in the workshop, which feels a bit funny to admit. But I also get to remember how writing supports me feeling more in my own life, more alive.

As someone who has been digging into my own history of trauma as well as collective trauma for years, it feels nice to be connected to other people doing similar work. As a younger writer, I felt so ashamed about the directions my writing took, particularly in wanting to write about violence I had experienced, so I feel really alive when I get to shape these spaces and invite other writers into them. I’m also just incredibly inspired by the quality of writing that I get to experience in these workshops literally every week. I get to remember how many incredible writers there are out there just looking for a room to write in.

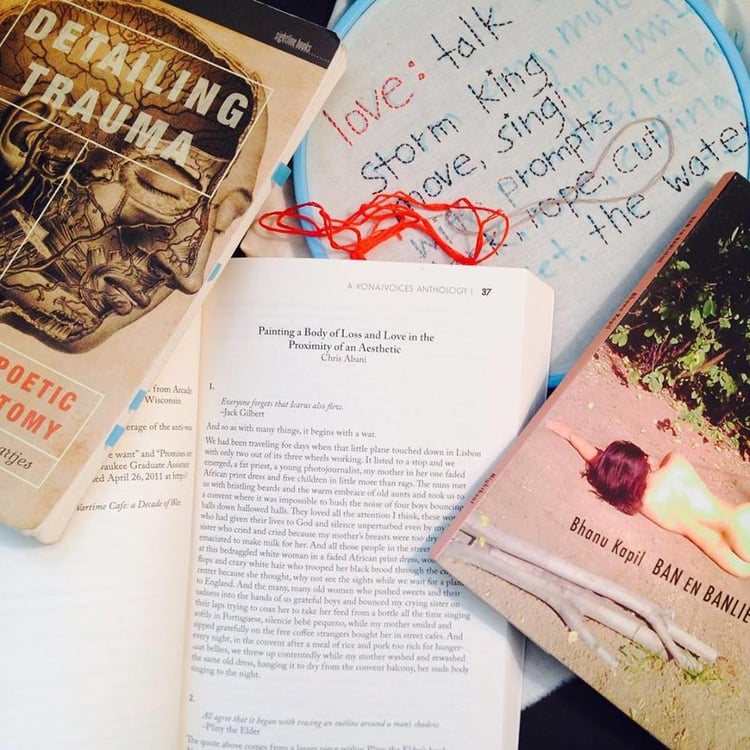

Photo: Jennifer Patterson (top). Class materials (bottom). Photo credit: Jennifer Patterson.

Support for the Readings & Workshops Program in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis and Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Trust, and Friends of Poets & Writers.

Upcoming screen adaptations of popular novels; Medium changes business model and cuts jobs; Central and South American books to read this year; and other news.

Mein Kampf becomes best-seller in Germany; Roxane Gay on her new story collection; Virginia school board considers proposal against “sexually explicit” literature; and other news.

Authors Yaa Gyasi and Emma Cline listed in Forbes’s 30 Under 30; Jonathan Lethem sells archive to Yale; Simon & Schuster deal controversy; and other news.

In this video from NBC's Late Night With Seth Meyers, reenactments of holiday-themed New Yorker cartoons come to life with live actors while editor David Remnick thoroughly explains the humor in each one. (Incidentally, Poets & Writers Magazine subscriptions also make a great holiday gift.)

Juan Felipe Herrera selects poet Ray Gonzalez for Witter Bynner Fellowship; Asian American fiction published in 2016; Ta-Nehisi Coates on politics and writing; and other news.

Siri Hustvedt on literature and science; novelist Ahmed Naji released from prison; notable books from indie presses; and other news.

Johnnierenee Nia Nelson is an award-winning author of five books of Kwanzaa poetry and two other volumes of poetry to promote social change. She serves as the San Diego County Area Coordinator for California Poets in the Schools, and teaches for San Diego's acclaimed Border Voices Poetry Program. She was the featured poet in the fifth annual El Cajon Friendship Festival with her creation of “A Taste of Kwanzaa” and a featured guest on KPBS’s “These Days” and “The Lounge.” Nelson also performed at San Diego City College in collaboration with Urban Bush Women and at the grand opening of San Diego’s new state-of-the-art Central Library.

“Light the candles

“Light the candles

beat the drums

pour the libation

for Kwanzaa comes

Bring forth the poet

let her speak

the message of Kwanzaa

the knowledge we seek.”

For the past several years, thanks to support from Poets & Writers, I have been the featured poet at the World Beat Center's annual Kwanzaa festival held in beautiful Balboa Park—the crown jewel of San Diego. Kwanzaa is a seven-day celebration of community, culture, and kin, which begins December 26 and ends January 1. Kwanzaa, created in 1966 by Dr. Maulana Karenga, is based on the year-end “first fruits” harvest festivals that have taken place throughout Africa for thousands of years. It is a family-focused observance steeped in African tradition and replete with rituals such as “drum call,” “ancestral roll call,” and a candle-lighting ceremony using seven candles (three red, three green, and one black), which represent the seven principles of Kwanzaa including pouring of libation and karamu (our feast consisting of African, African American, and Caribbean cuisine). Kwanzaa was explicitly designed to reaffirm and restore our rich African heritage.

Armed with a museum-quality kalimba, one of the many, many African names for what is known in America as a thumb piano, I (aka the Kwanzaa Poet) get to express with the resonating rhythm of this musical instrument the pride and the love I have for this progressive and uplifting holiday as a hush falls upon an audience awed by its chimes and my hypnotic chants and murmurings. Simply put, I love Kwanzaa. It has so much meaning and significance; so much to offer. I love its symbols, rituals, principles, and emphasis upon family. I love its history; the fact that it was created during the black nationalist movement of the 1960s as an act of cultural self-determination.

This year marks the fiftieth birthday of Kwanzaa and for several nights I get to perform such poems as “People in Me,” “Black Gold,” “Kwanzaa Is Rich,” “How I Rejoice,” and “Going the Distance”—poems found in the five volumes of poetry that I created in tribute to this revered commemoration.

The Kwanzaa festival is welcoming. All people are invited to “Come to the Kwanzaa table”—a table laden with fruits and vegetables (representing the fruits of our labor), African artifacts, and other symbols of Kwanzaa, such as the unity cup and the bendera (our flag also in the Pan-African colors of black, red, and green). The beauty and genius of Kwanzaa is in its centerpiece—its seven core principles (the Nguzo Saba), which begins with unity and ends with faith—values sorely needed in today’s climate of divisiveness and turmoil.

Kwanzaa celebrants are encouraged to don traditional West African and reggae attire, which creates a flurry of bright and bold colors, and vibrant geometric designs characteristic of the mud cloth, kente and Kuba cloth, and reggae fashions that friends and family members adorn. Elaborate and elongated African head wraps, as well as leather sandals typify the garments that guests wear. The plethora of sights and sounds associated with this colorful occasion along with the smells of healthy African and Caribbean vegetarian foods served at the World Beat Center’s karamu exemplify community-building and networking at its best.

Last year's festival attracted more than eight hundred celebrants. Each night's program begins with a drum call, a rendition of the African American National Anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and a prayer delivered in Twi, the ancestral language of the Akan people in West Africa. In addition to my poetry performances, this festival incorporates stilt dancing, drumming, singing, storytelling, live music, traditional African dancing, and capoeira (a martial art that combines elements of dance, acrobatics, and music). Cultural fufu for all!

“How I rejoice in the blackness of Kwanzaa

midnight black like Mother Africa

ebony black like.........”

Photo: Johnnierenee Nelson. Photo credit: Ben Nelson.

Major support for Readings & Workshops in California is provided by the James Irvine Foundation and the Hearst Foundations. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.