Where We Write: Hannibal, Missouri

In the second installment of Where We Write, a fiction writer takes a trip back home to Hannibal, Missouri, the boyhood home of Mark Twain and the town that still inspires her work, long after she's moved away.

Jump to navigation Skip to content

Articles from Poet & Writers Magazine include material from the print edition plus exclusive online-only material.

In the second installment of Where We Write, a fiction writer takes a trip back home to Hannibal, Missouri, the boyhood home of Mark Twain and the town that still inspires her work, long after she's moved away.

Novelist Eleanor Henderson discusses the beauty and necessity of backstory in fiction, offering a counterpoint to a previously published article in which novelist Benjamin Percy warned writers about the dangers of backstory.

Character calls forth writer. Writer calls forth reader. It seems straightforward—but is it? Novelist, filmmaker, and Zen Buddhist priest Ruth Ozeki explores the relationships embedded in every novel and work of fiction.

Fiction writer Aaron Hamburger got more than he bargained for when he signed up for a class in food writing. Instead of simply learning about a new genre, he also learned some valuable lessons about the one he'd been practicing for years.

Novelist Daphne Kalotay argues the merits of silence, even when it follows the publication of an author’s book.

Contributing editor Stephen Morison Jr. reports on the literary community in Cairo, Egypt, interviewing authors, publishers, and booksellers about the ongoing protests, freedom of speech, and the future of Egypt.

Benjamin Percy cautions beginning writers to avoid overusing backstory in their fiction, offering strategies for moving the story forward by slipping a character’s history into the dramatic present.

After navigating a devastating crisis, husband-and-wife poets Craig Morgan Teicher and Brenda Shaughnessy reflect on the fortifying powers of poetry and their commitment to their marriage and one another’s work.

After reading about one famed writer’s seemingly carefree existence, novelist Jesse Browner ruminates on his personal decision to forego the romanticized bohemian life and contemplates every writer’s choice to pursue the trade-offs writers face between artistic aspirations or financial security.

The Grub Street literary center has created a long-form fiction class that might offer a cure for the novel-writing anxiety that the traditionally story-centric MFA workshop isn’t equipped to resolve.

While caring for her dying grandmother, author Lisa Saffran gained new perspective on the richness of life in language as well as a renewed perseverance as a creative writer.

A look at the psychology of writers block and how scientific studies in creativity offer insight into how writers can use the tools they already have to break through.

My confusion came from a curious warning. Awash in a sea of writers and would-be writers in a drab-walled meeting room at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Conference a few years ago in Vancouver, B.C., I was listening to author Dinty W. Moore extol the virtues of creative nonfiction writing when suddenly he straightened his stout body and leaned across the podium. "Look out," he cautioned, his tone dire, "the journalists are coming!"

In the cyclone-ravaged country of Myanmar, where citizens face censorship and repression, contributor Stephen Morison Jr. speaks with authors who, despite the country's Orwellian police state, refuse to be intimidated and continue to write.

Joshua Bodwell explores the fiction behind this “writer’s writer” whose characters are as deep and complex as the man who created them.

Beijing, despite its cheap food and beer—two dollars worth of Chinese yuan will buy you a nice Chinese meal or a twelve-pack of Tsingtao beer—has yet to become the Paris of the 21st century, but an expat fiction scene is beginning to emerge.

Why do some writers prefer company and background noise, while others need isolation? Why do some need the magical monotony of sameness, and others the inspiration of variety? What does it mean for a writer to be locked into a place? What does place even mean to a writer?

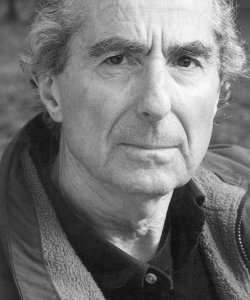

A literary look at the career of prolific author Philip Roth, our Great American Novelist.

Let me be the last—the absolute dead last—to point out that we're in the midst of a memoir craze. My favorite form of procrastination used to be computer solitaire, but now I prefer to chat on the phone with my writing friends and discuss the ongoing boom in autobiographical literature. We speculate like housing developers prognosticating on the real estate market. Will the bubble pop? Will prices continue to rise? Will market trends ever again veer toward literary fiction?

It took a long time to write these words. I'm not referring to the psychosomatic affliction known as writer's block. I mean the delays caused by the process of composition and revision.

From Thoreau to Arthur Miller for centuries writers have been escaping to personal cabins—some even hand built by the writers themselves—for the solitude necessary to slip inward.

At no time on my book tour did I jump up and down, wave my fists, and scream, “It’s a novel! That means fiction!” At least I don’t think I did. It’s hard to be sure, because, in my head, I had that tantrum about three times daily as I traveled from town to town in southern Michigan, reading, signing books, and attending the Ann Arbor Book Festival. You see, my novel, Flight, was set in that region, where I had lived during my high school and college years.

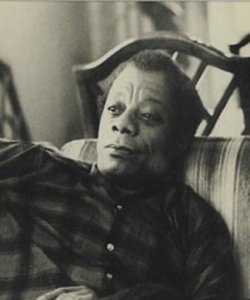

Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin’s best-known book, was published in 1955 by Beacon Press. Baldwin’s editor then was Sol Stein, whom he’d known since high school. This essay is an excerpt from Stein’s Introduction to Native Sons by Baldwin and Stein, which will be published by One World, an imprint of Random House, next month. The book includes correspondence between Stein and Baldwin that produced Notes of a Native Son.

Only weeks before he turned 55, my father, the poet William Matthews, delivered a manuscript of poems to Peter Davison, his longtime friend and editor at Houghton Mifflin. It turned out to be the last book he wrote. He died of a heart attack on November 12, 1997, the day after his birthday.

At some point every writer must turn her attention from the art of creating to the business of selling. And while many authors would like to avoid the industry altogether, a basic understanding of it—from the top five houses to the independents—is an unavoidable necessity.